Discover more from Ag Data News

Two weeks ago, Russia invaded Ukraine, inflicting horrific violence on the Ukrainian people and capturing the attention of the world. Russia and Ukraine are large producers and exporters of agricultural commodities. How will the war will affect the world's food supply?

My answer: This will have a big effect on world agricultural markets, but not that big. The US government should not incentivize additional production in response.

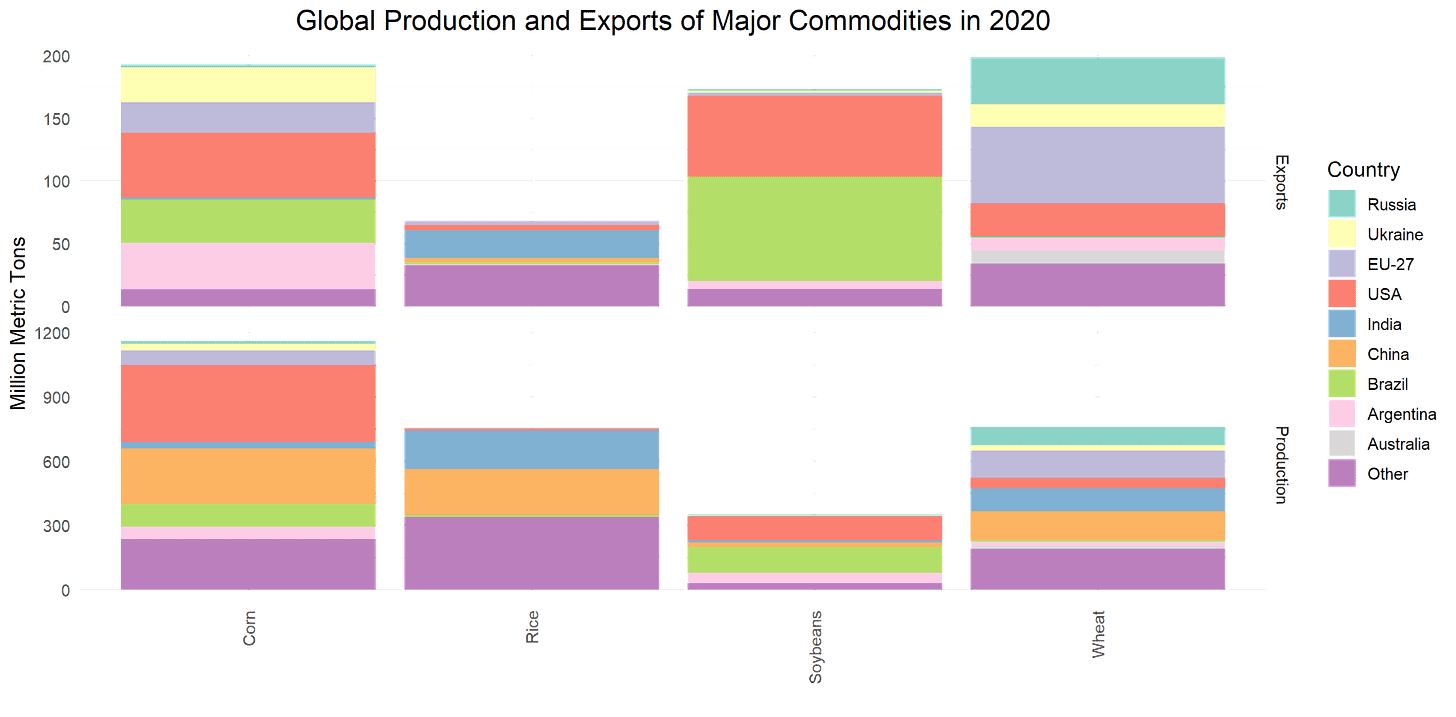

Russia produces 11% of the world's wheat and Ukraine produces 3%. These countries make up a larger proportion of global exports. Russia accounts for 19% of the global wheat export market and Ukraine 9%. Ukraine is also a major corn exporter, accounting for 14% of exports. Neither country is a large player in rice or soybeans, which are the other two major agricultural commodities in the world.

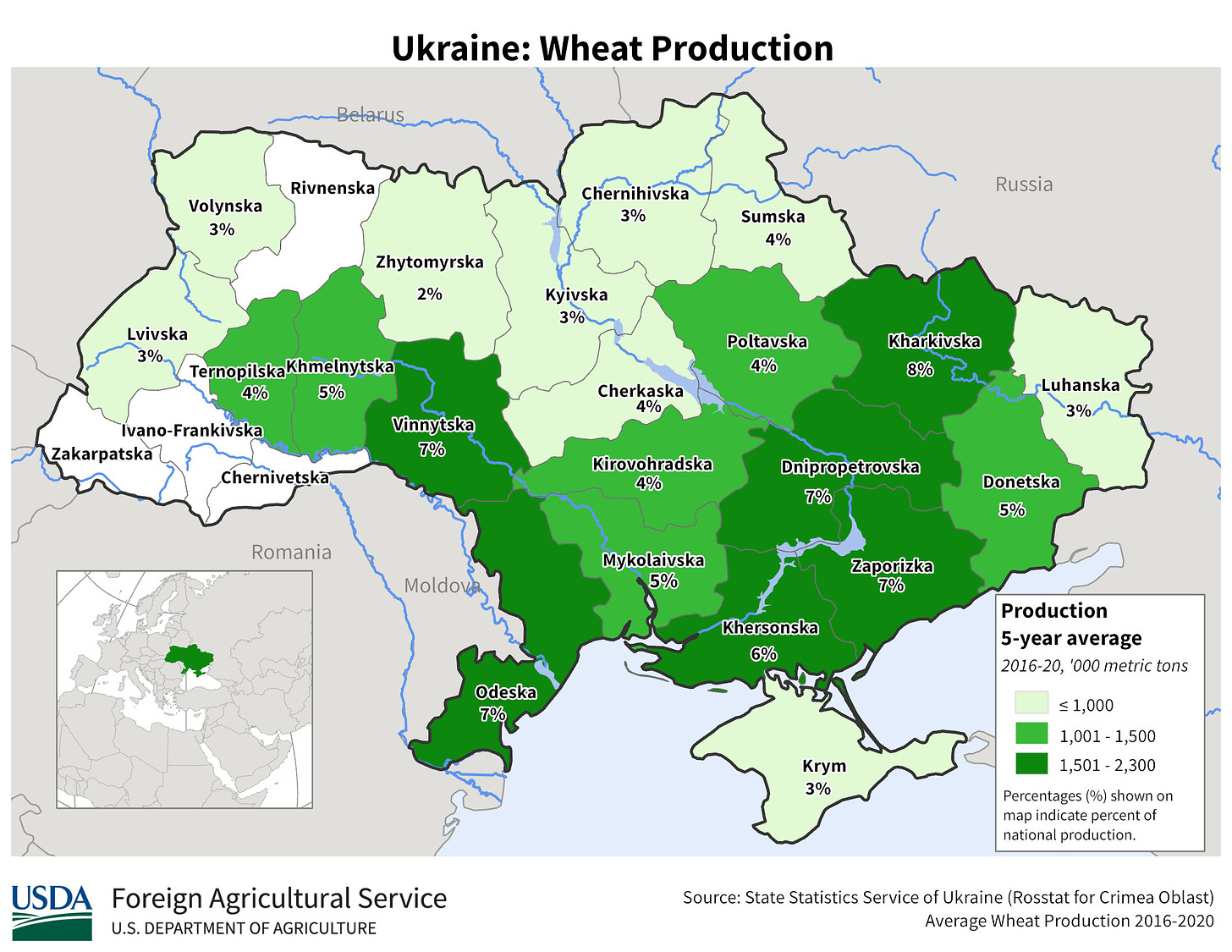

Much of Ukraine's exports flow out through the Black Sea, where ports are currently closed and may stay closed for a long time. Today, Ukraine banned wheat exports. Sanctions against Russia and the potential withdrawal of western commodity trading companies will drastically reduce the market for its exports. China and India appear hesitant to sanction Russia and they are the two largest consumers of wheat, but they already produce enough domestic wheat to satisfy their needs.

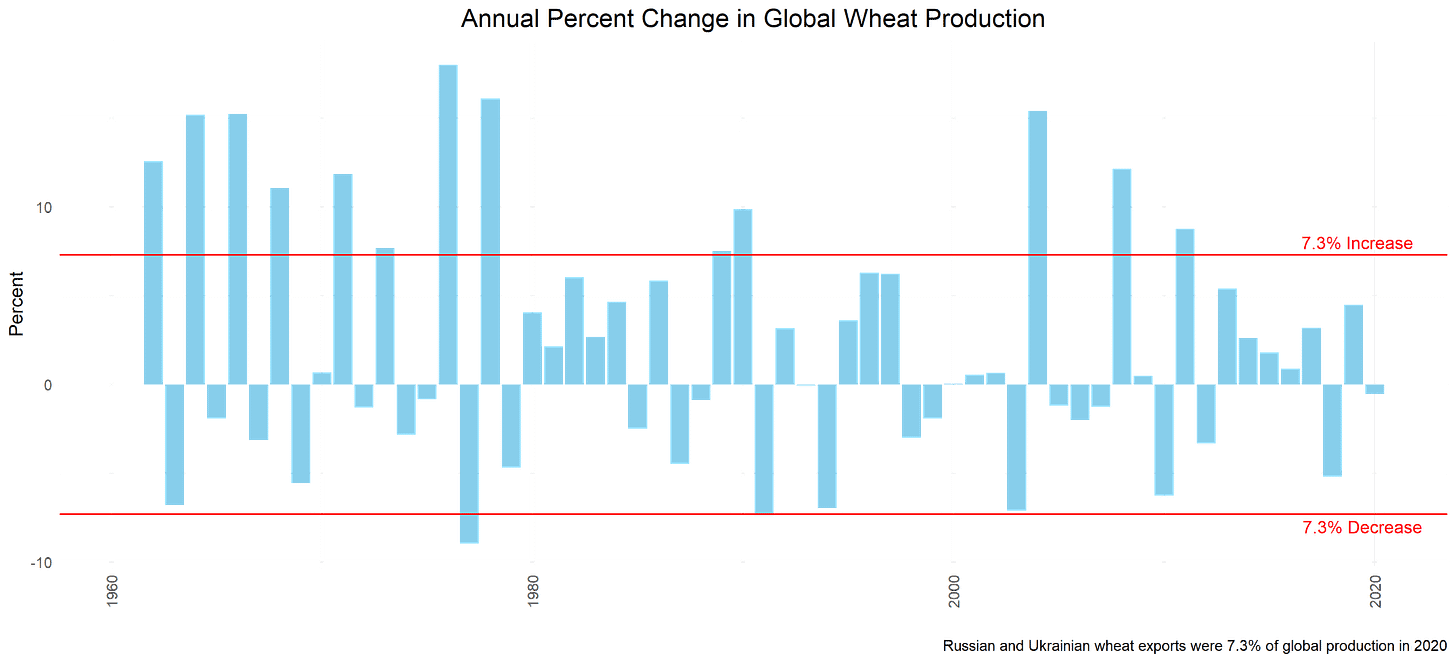

What if the world has lost access to the 55 million metric tons of wheat and 30 million metric tons of corn exported from Ukraine and Russia? These quantities represent 7.3% of global wheat and 2.6% global corn production.

The first thing that would happen is prices would increase.

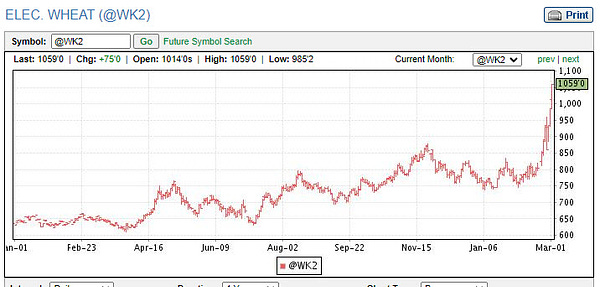

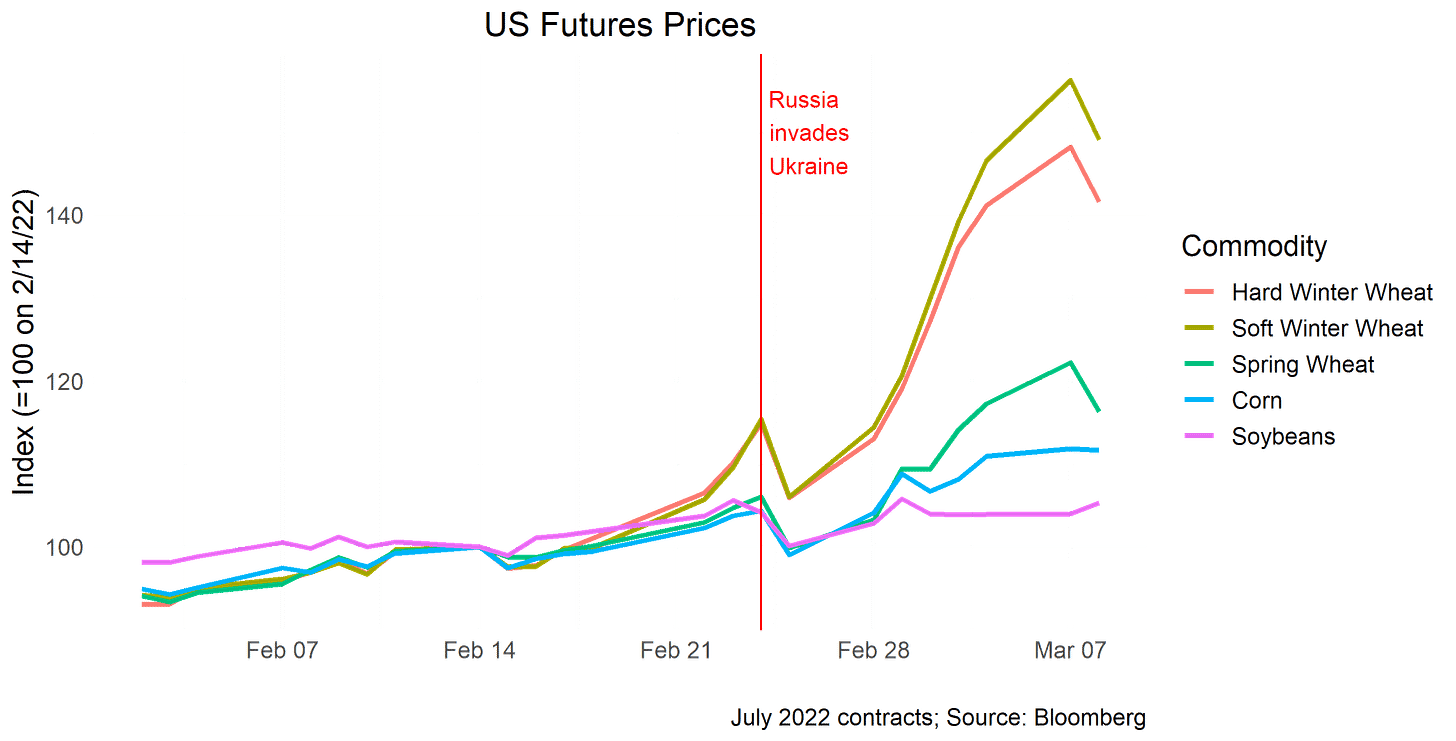

Wheat futures prices have increased since the day before the invasion (February 23), but by different amounts depending on variety. Winter wheat is up about 30%, whereas spring wheat is up 10%. Corn prices have increased by 7% since February 23 and soybean prices are unchanged. Winter wheat prices did drift up in the week before the invasion as Russia built its military presence on the border. Since February 14, winter wheat is up about 45%, spring wheat 16%, corn 12%, and soybeans 5%.

Winter wheat prices have increased by more than spring wheat because winter varieties make up about 95% of Ukrainian wheat and 70% of Russian wheat. Farmers planted their winter wheat several months ago. It went dormant during the winter and will resume growth in the spring before harvest in the summer. The rest of Ukrainian and Russian wheat will be planted in the next few months (spring) for harvest in the late summer.

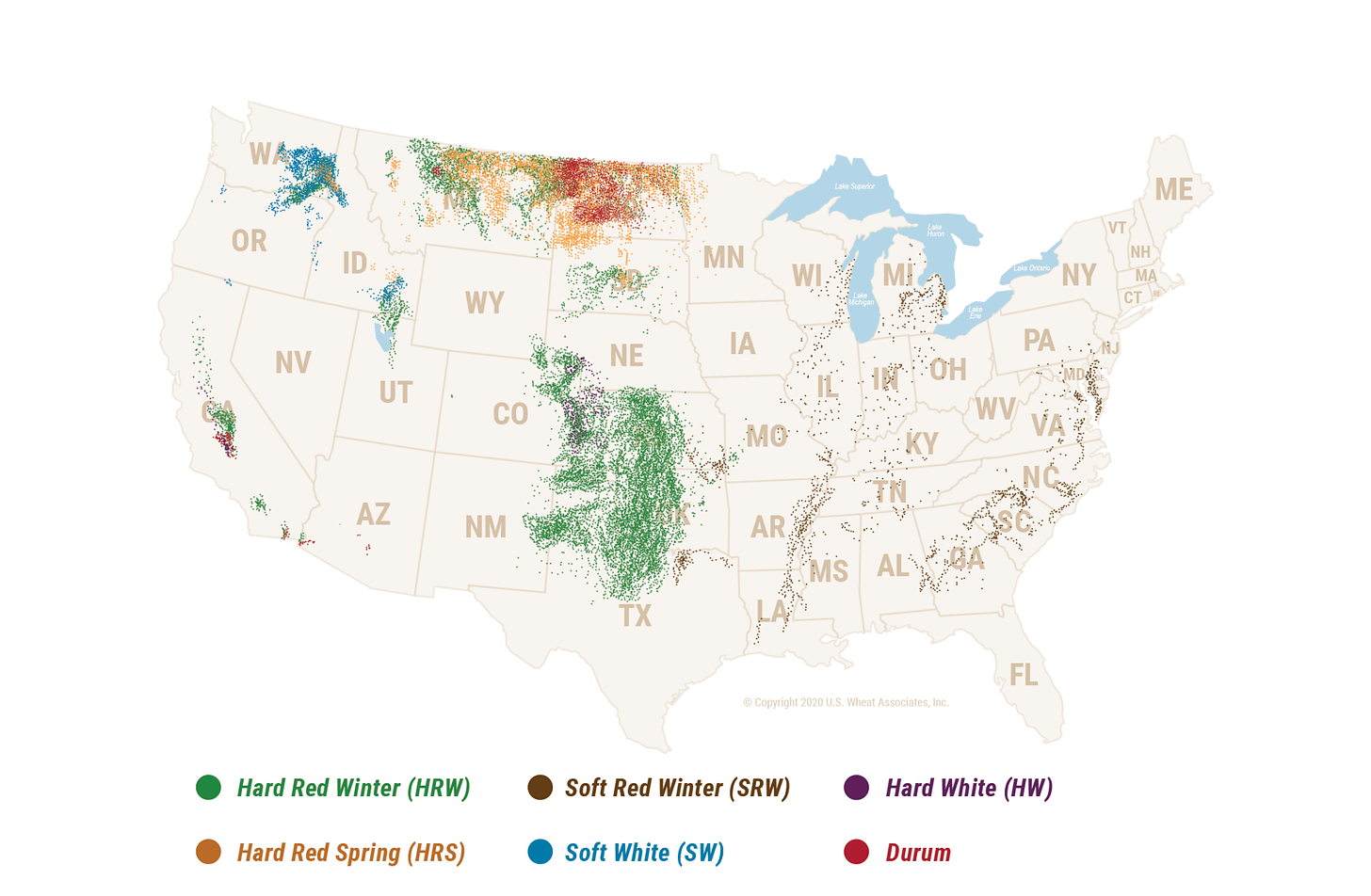

About two thirds of US wheat is winter wheat, mostly grown in the southern great plains. Bernard Warkentin originally brought hard winter wheat from Russia to Kansas in the 1870s. US spring wheat is grown mostly in the upper great plains states, which last year experienced a severe drought that reduced yield by 33%.

Based on the observed price increases, we can infer how much grain that traders think the world has lost. In doing so, it is important to account for any substitutions across crops. For example, a reduction wheat exports from Russia and Ukraine may lead farmers in other countries to plant more wheat and less corn, and it may cause consumers to eat more rice and less wheat.

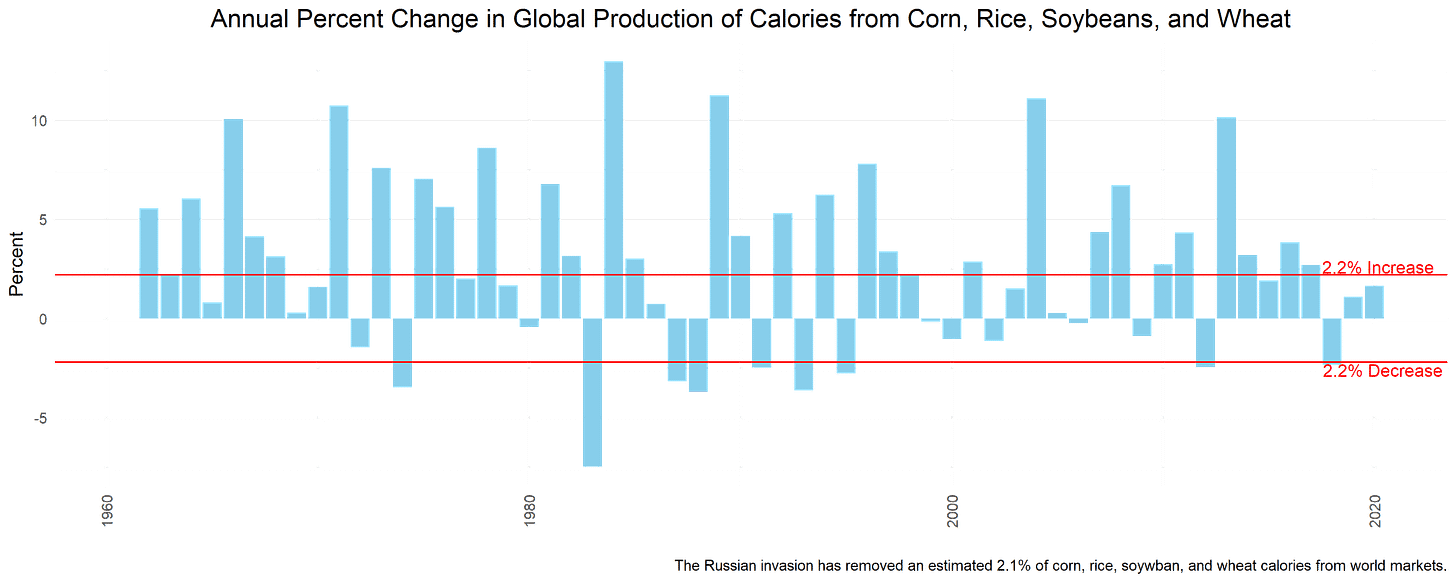

One way to do this is to aggregate across commodities, which requires measuring quantities in comparable units (e.g., dollars or calories) because a ton of rice is a very different food product than a ton of corn. In a 2013 paper. Mike Roberts and Wolfram Schlenker studied supply and demand for total calories from corn, rice, soybeans and wheat combined. They found that, for every 1% decrease in calories from these commodities, the average price increases by 7%. Students in my ARE 231 class have re-estimated this relationship using more recent data, and using price weights rather than calorie weights, and obtained similar results.

On February 14, the average price of the four commodities was 15.1c per 1000 calories. By March 8, it had risen to 17.4c, an increase of 15.2%. Using the Roberts and Schlenker factor of 7, this implies a 2.2% decrease in available supply of calories. Removing 55 million metric tons of wheat and 30 million metric tons of corn entails a 2.7% reduction in available supply of calories from the big four commodities. (Here’s an Excel file containing these computations.)

So, it seems the markets are banking the world losing about three quarters of Ukrainian and Russian grain exports (2.2/2.7). Given the large increase in winter wheat prices relative to the other commodities, most of the loss is from wheat.

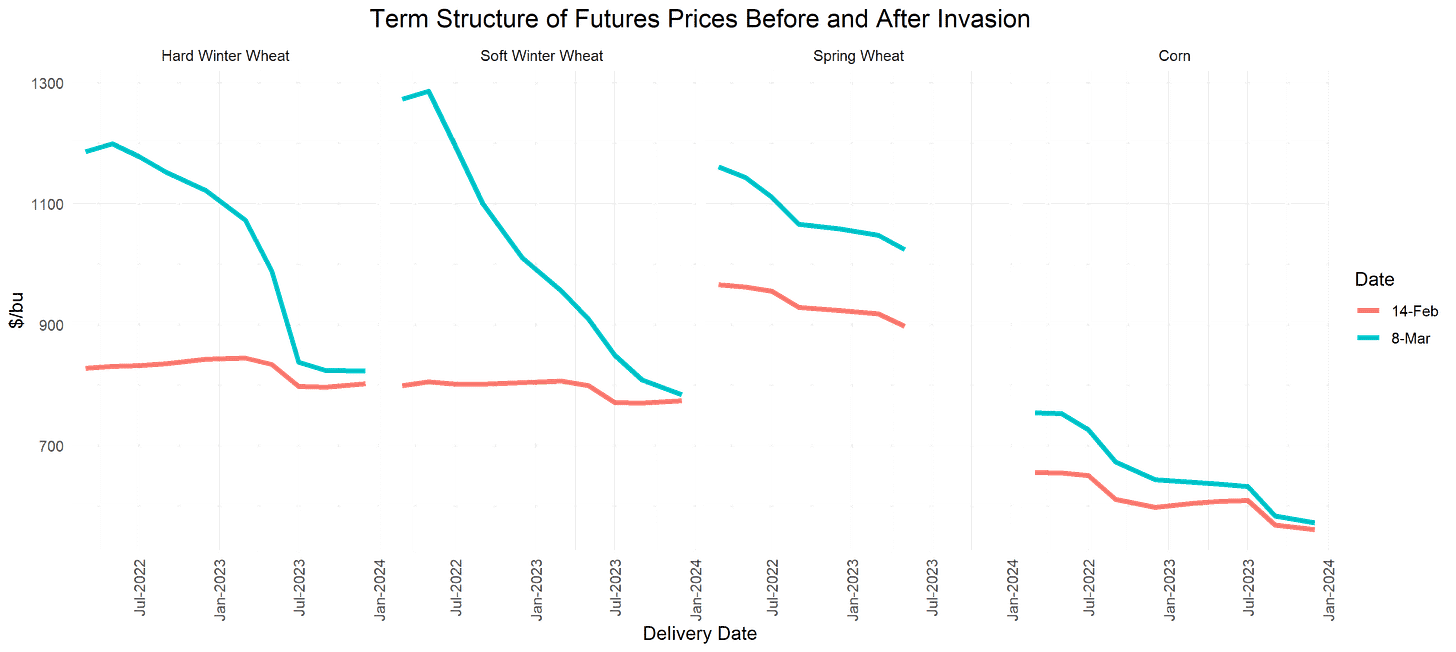

Traders expect this shock to last only a year. Winter wheat futures prices for delivery after July 2023 barely increased after the invasion. The same is true for corn. The spring wheat market was already tight because of last year's drought and traders expect it to remain tight beyond 2023.

How common are market shocks of this magnitude? Russian and Ukrainian wheat exports were 7.3% of global production in 2020. Wheat production declined 6.3% in 2010, in part due to a drought that reduced Russian production by 20 million metric tons. Similarly large declines also occurred in 1991, 1994, 2003, and 2018.

From the analysis above, the observed price increases are consistent with a 2.2% decrease in available supply of calories from corn, rice, soybeans, and wheat. Similar declines occurred in 2018, in part due to drought in Argentina and lower wheat acreage in Russia, and in 2012, in part due to drought in the US.

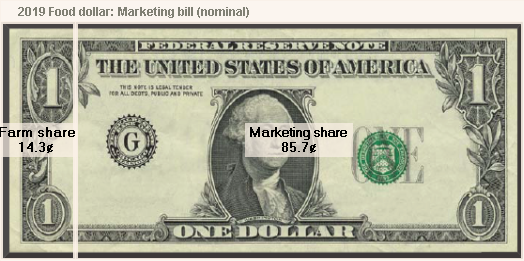

The increase in wheat prices will not cause massive increases in the price of American bread. Most of the price of food is determined by the cost of processing, packaging and marketing. The USDA estimates that farm gate sales of food commodities made up 14% of the retail value of food in 2019. If farm prices increase by 50%, then we would expect food in the grocery store to increase by 7%.

There have been calls for the US government to take action to increase production this year to offset the lost exports from Russia and Ukraine. I don't think such measures are necessary or will do much to relieve the pressure on markets.

On twitter, Scott Irwin proposed releasing acreage from the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). There are currently 22 million acres enrolled in CRP, so it is a potential source of additional production. Based on observed price changes, the biggest need is for winter wheat, but the 2022 US winter wheat crop is already in the ground. So, even if some CRP land could be brought back into production quickly, and even if it were productive land, it would not be quick enough to increase winter wheat supply this year.

Another idea is to suspend the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS), which is the law responsible for 10% of US gasoline being ethanol made from corn. The idea is that less corn going into gas tanks would free up more grain for the food system. On twitter, Scott Irwin pointed out that we tried reducing the RFS requirements by exempting small refineries from compliance, which resulted approximately zero change in ethanol use.

Interestingly, the ethanol industry has advocated for increasing the amount of ethanol in gasoline to relieve pressure on gasoline prices. This will also not work. We are stuck with ethanol as 10% of gasoline for at least the next few years whatever the government does with the RFS. I will write more on this in the coming weeks.

In summary, the Russian invasion is a large shock for agricultural commodity markets, but not historically large. Markets and trade patterns will adjust to absorb it. Farmers around the world will produce more and consumers will cut back or substitute. The transition may be difficult in some places, especially countries such as Egypt that typically rely on wheat from Russia and Ukraine. Helping such countries find alternate suppliers would be better policy than suspending CRP or RFS.

This assessment may change depending on the trajectory of the war.

Update 1: Changing Ethanol Policy Isn't Going to Help

Update 2: Russia, Ukraine, and Food Supply: Look at the Prices

Update 3: Was I Wrong About the Global Food Crisis and Inflation?

To view global production, consumption and trade of these commodities, check out our "US Major Crops: World Trends" data app. View and download data from the comfort of your web browser.

I created the graphs in this article using this R code.

Subscribe to Ag Data News

Agriculture, Economics, and Data

Good data and research on wheat exports, but overall a terrible article and title.

Russia's (and Ukraine's) outright wheat exports are not the only factor in world food.

Escalating energy prices - both diesel and propane - will impact grain production.

So will fertilizer prices.

Then there's the pandemic-induced shortages in labor and semiconductors --> tractors.

A terrific article, but this war is just one of the factors potentially fueling an agricultural crisis, the others being rising natural gas prices and climate change. From a macro view, it seems like we're heading down this road and the war is just adding fuel to the fire.