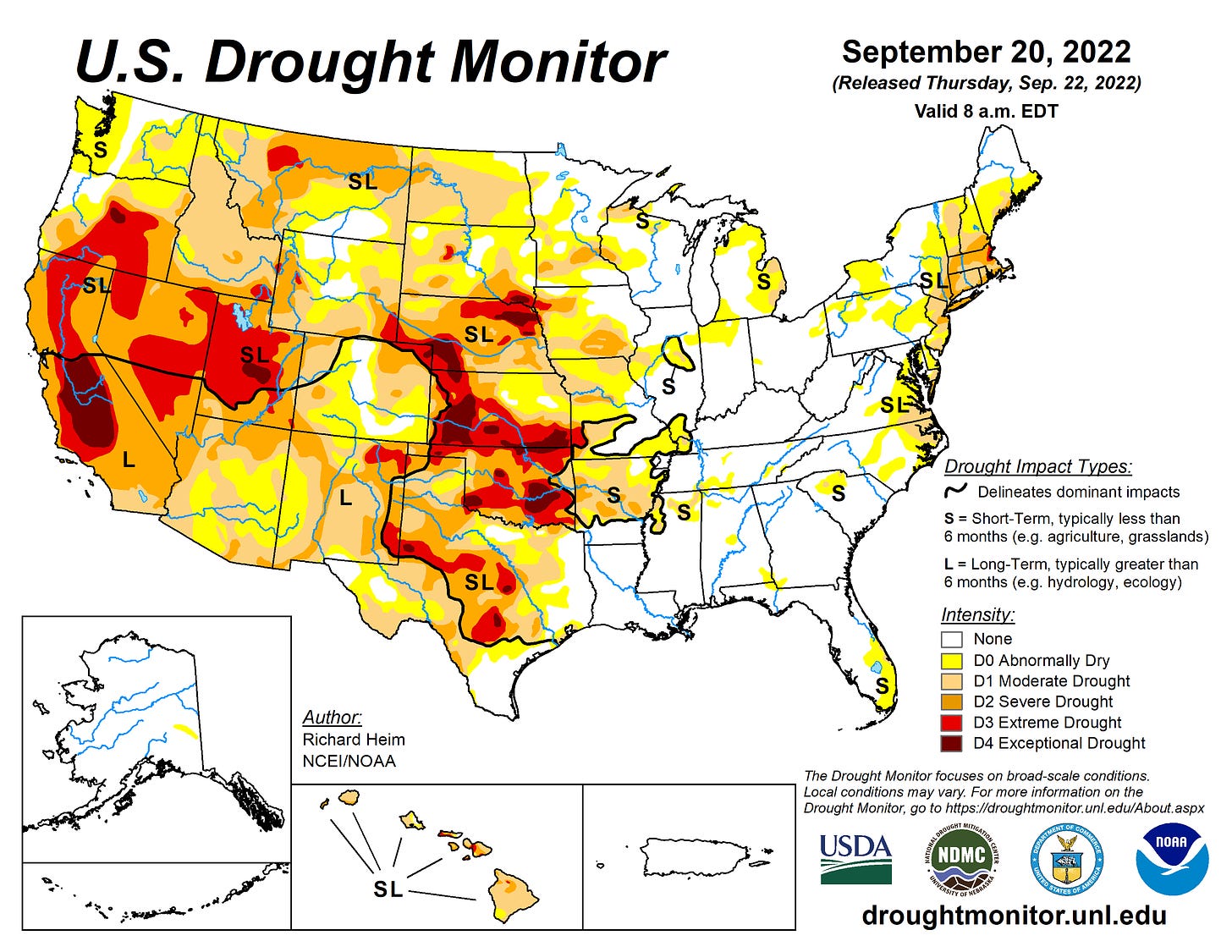

Climate change is messing with the weather. We got an inch of rain in Davis last week (it felt like more). I don't remember the last time it rained in September. Two weeks before that, we experienced a week of extreme heat in which the temperature reached a record high of 116°F (47°C). All this amid a three-year long drought that, in spite of the rain storm, shows no sign of abating.

Meanwhile, a massive hurricane is pummeling Florida, and parts of Kansas are in severe drought. The northern great plains experienced extreme drought last year. And I haven't even mentioned Pakistan, China, or Europe.

It is natural for us to observe these events and wonder how they will affect us. From an agricultural perspective, we wonder whether an extreme event will cause crop shortages and inflate prices. Our wonder is often fueled by media reports that shortages and higher prices are just around the corner.

Most of the time, however, such far away events hardly affect us at all.

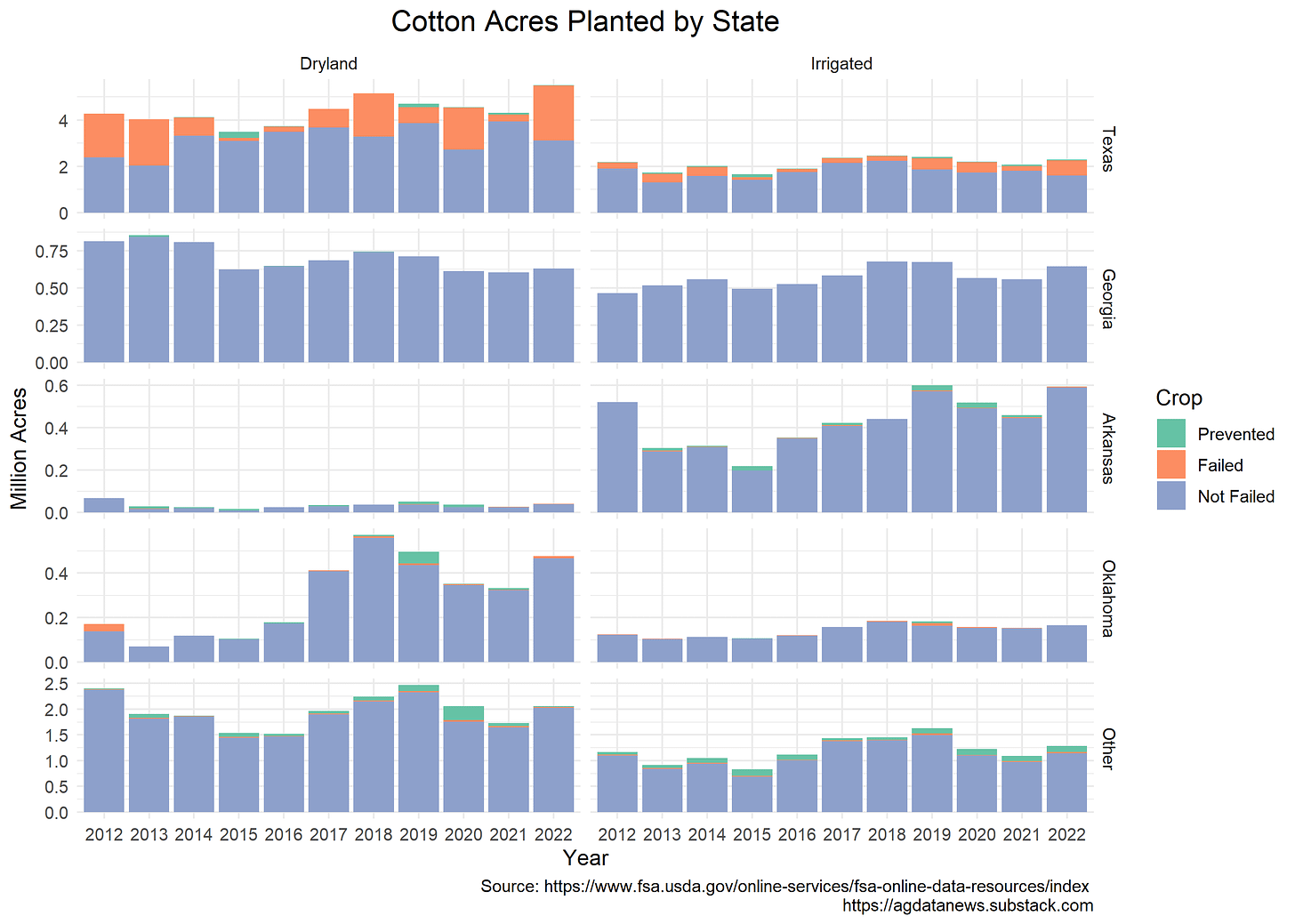

Consider cotton, which is the fifth biggest crop in the US by value. Texas produced 44% of American cotton last year. It is the largest cotton-producing state in the nation, producing more than three times as much as second-ranked Georgia.

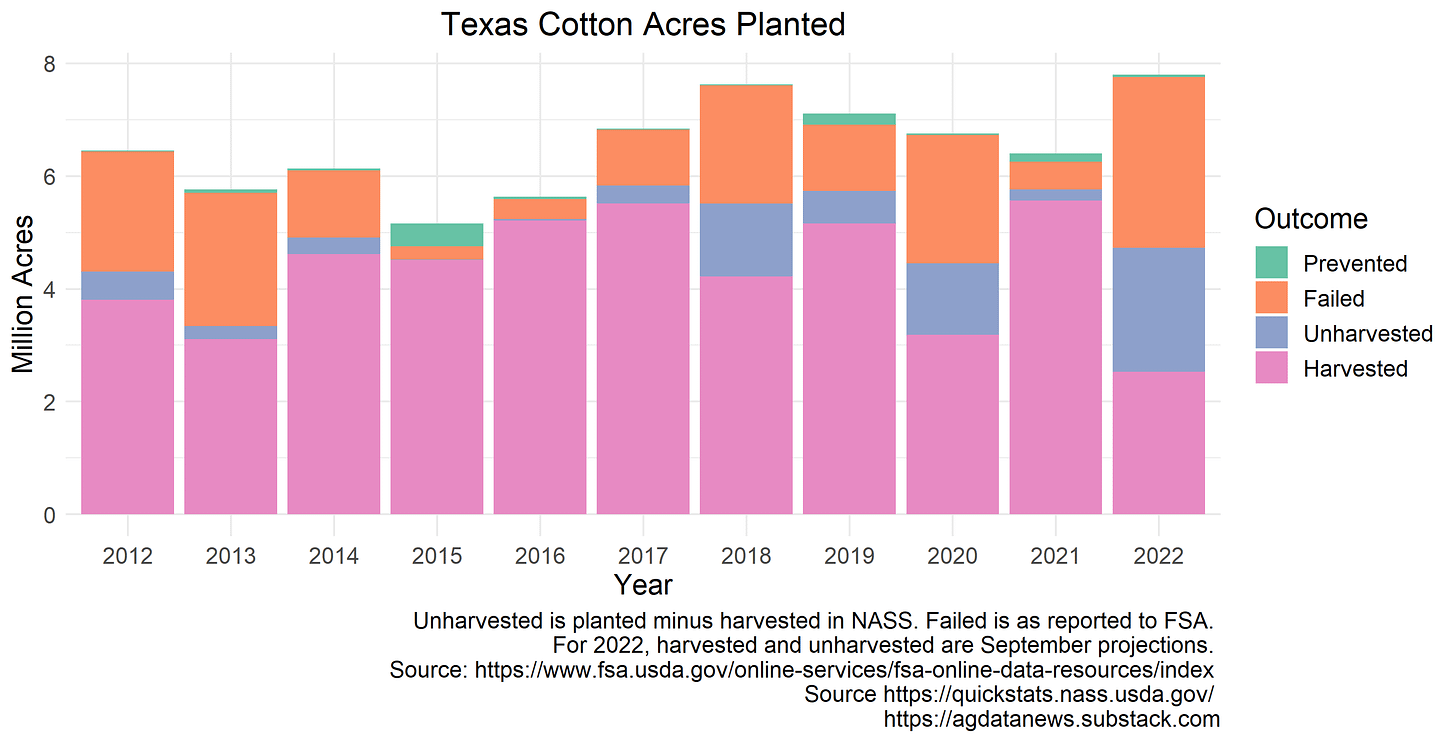

This year, USDA projects that only 32% of planted Texas cotton acres will be harvested. Texas farmers planted 7.9 million acres and have already reported that 3 million of these acres have failed. USDA projections imply that another 2.2 million cotton acres will not be worth harvesting. This is a disaster.

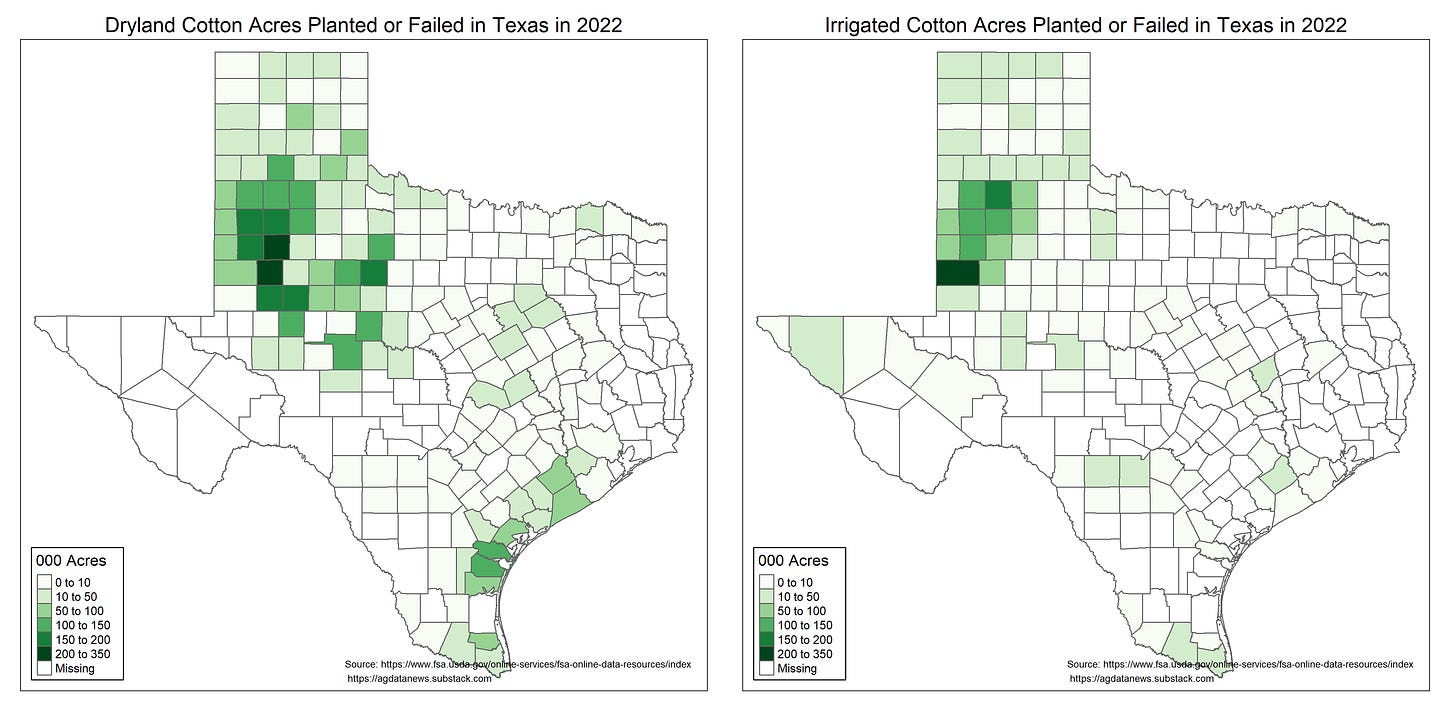

Most Texas cotton is grown in the panhandle plains part of the state, about two thirds of it on dryland, i.e., unirrigated. The most common reason for failure of a dryland crop is lack of rain. The irrigated and dryland acres are close together, suggesting that farmers have some discretion over which acres to irrigate based on water availability.

Most failed cotton crops have been on dryland farms, which are at the mercy of mother nature.

Failed Texas cotton crops are not new. There were also significant failed cotton crops in 2012, 2013, 2018, and 2020. These events underlie the big crop insurance payouts to cotton growers in the past decade. States other than Texas have very few failed cotton acres.

(USDA NASS no longer projects harvested acreage separately by irrigation status, so the figure below does not delineate harvested and unharvested acres.)

So, things are bad for cotton in America's biggest-producing state. In addition, devastating floods in Pakistan this month have destroyed up to half the crop. Cotton prices must be through the roof, right? T-shirt prices must be skyrocketing, right?

Wrong. Cotton futures prices for delivery in December have dropped significantly in the last month.

So, what's going on?

First, Texas and Pakistan together make up less than 10% of world production, and the amount of lost cotton is about 5% of production (3 million bales each). If an extreme event hits two relatively minor production locations, then it matters little in aggregate. Macroeconomic factors may be suppressing demand much more than the lost supply.

We saw the same thing with California rice this year. Due to lack of irrigation water, farmers were prevented from planting 55% of their intended acres, but the global effects of this loss are small because California is not a large rice producer relative to the rest of the world.

We have seen something similar with Russia's invasion of Ukraine. I have argued repeatedly that people have vastly overstated how much the invasion affected world food prices and supply.

The second factor for cotton is that the world is carrying over almost a year's worth of production from last year. Traders can use these inventories to offset production losses.

The third factor is that there is only about 50c worth of cotton in a t-shirt. As with most agricultural products, the vast majority of the retail price is determined by processing, packaging, transportation, and marketing.

Now, removing some supply from the market means that prices are a little higher than they otherwise would be. Maybe t-shirts now cost 5c more. If you add this little increase up across all the people who might buy the product, then you might get a large number. This number is useful for economists to compute to measure the losses associated with the event, but the little price increase is typically too small for individuals to notice.

On the other hand, the people directly affected by these events often incur great hardship. Let's focus our energy on them.

I made the graphs in this article using this R code.

Amazing that we subsidize water intensive crops alfalfa rice corn to be grown in a desert when they can easily be produced where it actually rains. Maybe if the water rights out west were in line with reality then you would not be producing alfalfa and rice and corn in California along with the dairy cattle that are dependent upon the alfalfa and corn.

What damage is enough to tip the global prices one way or another? As a traded commodity don't they fluctuate on the whims of investor sentiment? So even if what you say is true could they overestimate the problem, and cause prices to go up? Also with California being a bread-basket for US (plus exports) but relying on imported water - could we be close to realizing some real consequences on prices? In NZ tomatoes are the thing that just has not come down at all...since COVID and some tomato disease impacted them more than a year ago....