Petroleum Diesel is Disappearing from California

The state’s low carbon fuel standard is driving a shift to renewable diesel.

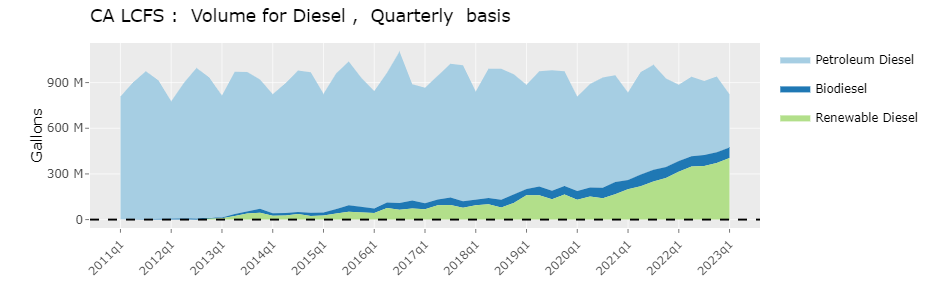

California trucks and trains burn about 3.5 billion gallons of diesel per year. Five years ago, petroleum supplied 85% of diesel. In the first quarter of 2023, less than half the state's diesel came from petroleum. Most California diesel is now made from animal fat, corn oil, soybean oil, or used cooking oil.

This trend is likely to continue. Under current policy, there is a high chance there will be no petroleum diesel used in the state in 2030. That’s one conclusion of a recently released working paper by Jim Bushnell, Gabriel Lade, Julie Witcover, Wuzheqian Xiao, and me.

What are the Alternatives to Petroleum Diesel?

Rudolf Diesel experimented with multiple fuel sources when developing his engine in the late 1800s, including kerosene, coal dust, and vegetable oils. At the 1900 World's Fair in Paris, he displayed a prototype that ran on peanut oil. Modern diesel engines require a fuel that is less viscous than vegetable oil, so pouring peanut oil into your diesel engine is a bad idea. However, two products of vegetable oils and fats work well in modern diesel engines: biodiesel and renewable diesel.

Biodiesel is produced through a chemical process that reacts organic oils and fats with alcohols and catalysts. Biodiesel has some limitations that curb its use, including a lower energy density than petroleum diesel, potential corrosion of storage tanks, potential clogging of fuel lines, and sensitivity to the cold.

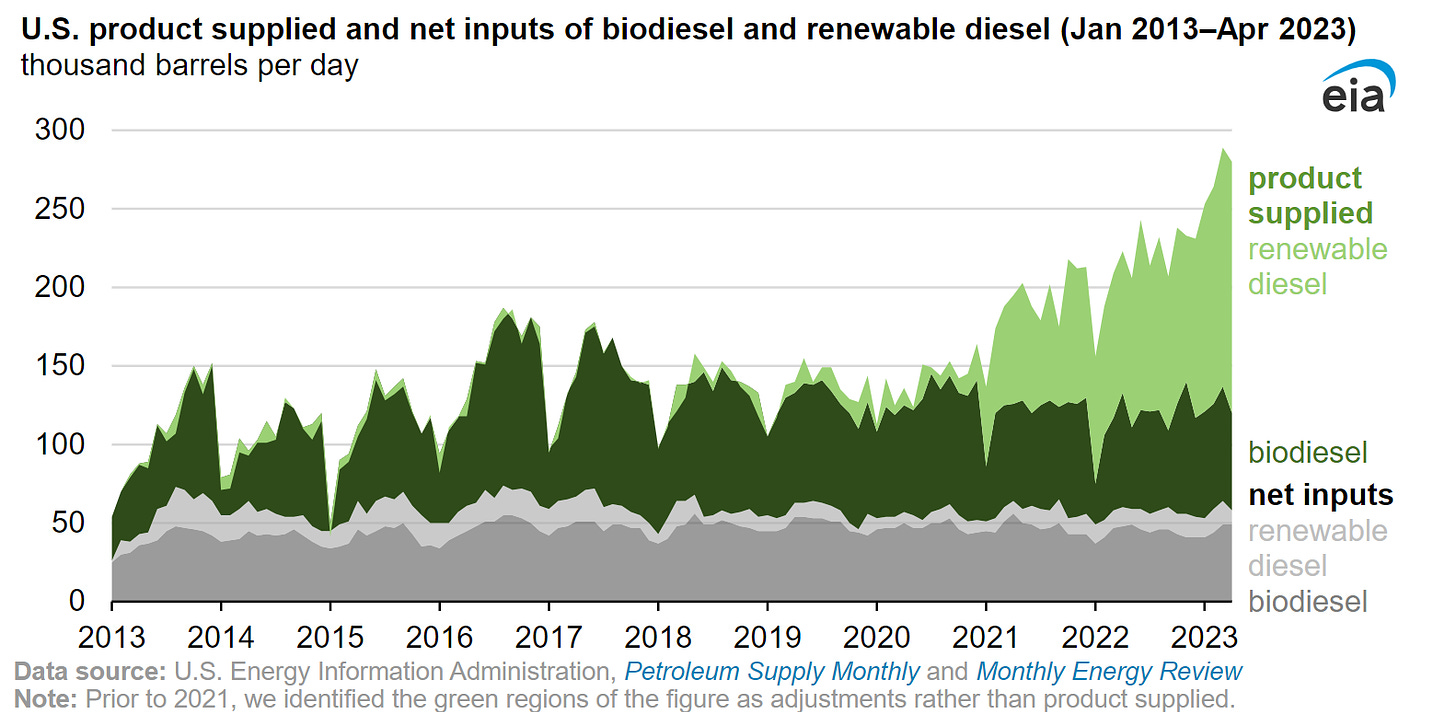

Renewable diesel doesn’t have the drawbacks of biodiesel, but it is more expensive to produce. It is created by reacting hydrogen and catalysts with oils or fats under high temperature and pressure. This process removes oxygen, leaving a fuel that contains only hydrogen and carbon; it is a hydrocarbon just like petroleum diesel and can be used in diesel engines without restriction. Renewable diesel production capacity in the United States has boomed in the past couple of years as oil refineries have repurposed to produce the fuel. Almost all United States renewable diesel is consumed in California.

Why have Biodiesel and Renewable Diesel Increased So Much in CA?

California's Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) is a state policy that currently requires a 20% reduction in the carbon intensity (CI) of transportation fuels below 2010 levels by 2030. Similar to CAFE and RPS, the LCFS requires the average CI across all transportation fuels to be at or below a specified target. This policy is the primary driver of the increase in biodiesel and renewable diesel in the state.

Here's how the LCFS works. The California Air Resources Board determines the CI of all the fuels in the state using a life cycle analysis that accounts for tailpipe emissions as well as potential emissions throughout the fuel production process. There are currently 815 active fuels with an approved CI.

For example, renewable diesel produced by co-processing soybean oil with fossil feedstock in a diesel hydrotreater at Chevron's El Segundo refinery using soybean oil transported by rail to California has CI of 51.74 grams of CO2 equivalent per megajoule of energy. That's a mouthful, and it illustrates the myriad ways that even renewable fuels can emit carbon. Petroleum diesel has a CI of 100.45, almost twice as large.

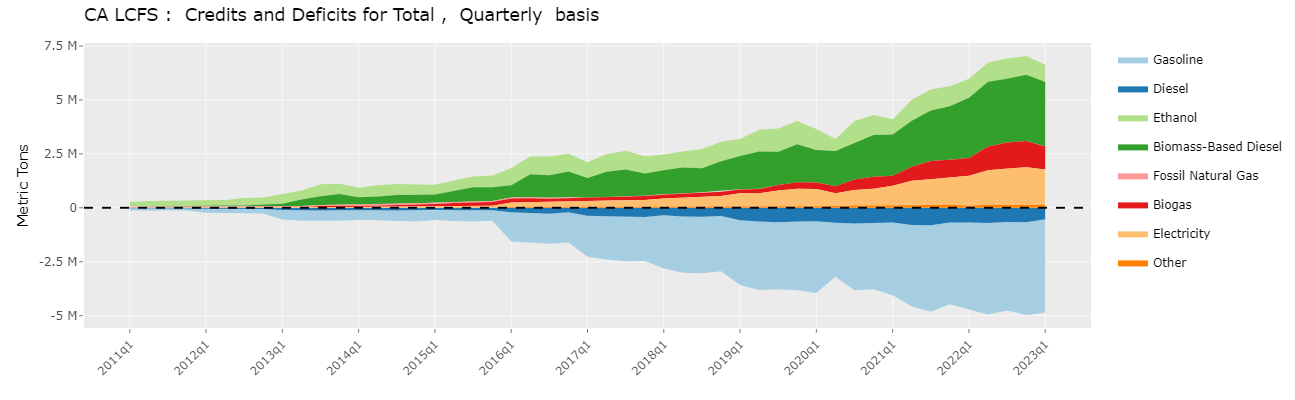

In 2023, the CI target for diesel is 88.15, which is 11% below 2010 levels. A fuel supplier could hit the target with a blend of 75% petroleum and 25% renewable diesel. In aggregate across all transportation fuels, the total deficits (number of CI units above the target) need to be offset by the total credits (number of CI units below the target). Fuel suppliers with a net deficit can reach compliance by buying credits from suppliers with a net credit.

In the first quarter of 2023, petroleum diesel generated 532,000 metric tons of CO2 deficits in California. Biomass-based diesel (BBD), which encompasses both biodiesel and renewable diesel, generated 2.99 million metric tons of credits, which more than offsets the deficits from petroleum diesel and is substantially more than other prominent credit-generating fuels such as ethanol, electricity, and biogas.

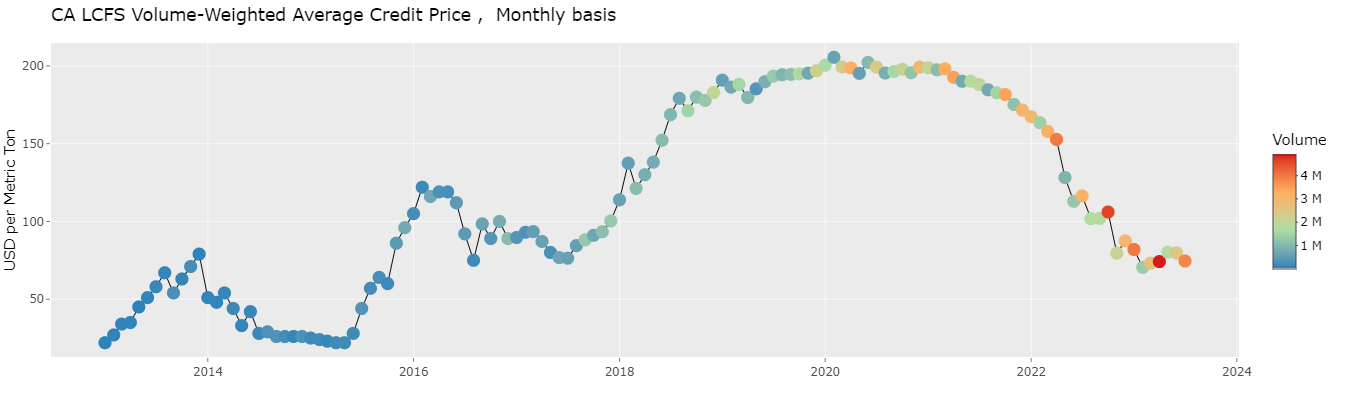

In 2019 and 2020, credits were scarce, which pushed credit prices to their ceiling of just over $200 per ton. The boom in renewable diesel has relieved pressure on the LCFS, and as a result credit prices have dropped. In response, the Air Resources Board is considering tightening the targets from the current 20% to between 25% and 35% CI reduction below 2010 levels by 2030.

Will the Renewable Diesel Trend Continue?

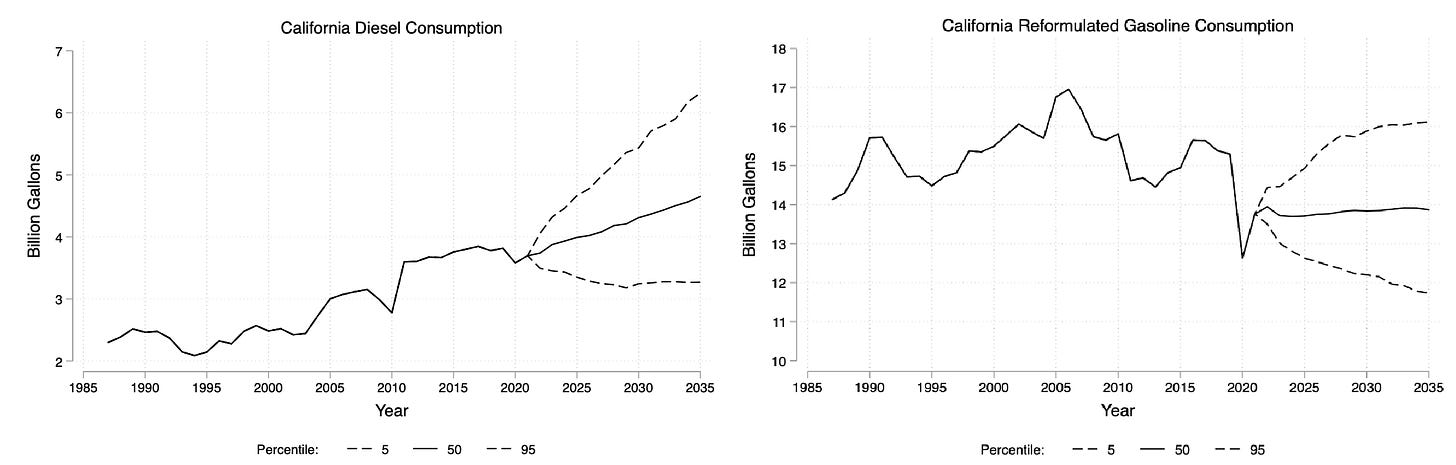

To answer this question, my co-authors and I built a statistical model (a cointegrated vector autoregression) to forecast fuel demand through 2035. The model uses six quarterly variables: California vehicle miles traveled, California gross state product, Brent oil price, soybean price, California diesel consumption, and California gasoline consumption.

The model accounts for uncertainty. We don't know what will happen in the state economy in the next 12 years, so it is better to predict the range of possible outcomes and their associated probabilities rather than calculating a single prediction. Our median forecast is for consumption of diesel-equivalent fuels to continue growing as the state economy grows and for consumption of gasoline equivalent fuels to remain flat as fuel economy continues improving. There are a wide range of possibilities around the median.

Next, we take these forecasts and ask what it would take to achieve LCFS compliance.

This exercise requires numerous assumptions about the number of credits from various sources. We treat all credit generating fuels as price insensitive except BBD. Our main assumptions are that (i) ethanol will remain 10% of the gasoline pool, (ii) the number of light-duty electric vehicles (EVs) will increase steadily to 5 million in 2030 and 10.5 million in 2035, (iii) each light-duty EV displaces 80% of the miles that would have been driven by an internal combustion engine vehicle, (iv) the number of credits from biogas will approximately double by 2030 and remain constant subsequently, and (v) the fleet composition of medium and heavy-duty vehicles will follow projections in the 2022 Scoping Plan Scenario. See the paper for additional assumptions covering forklifts, alternative jet fuel, and other components.

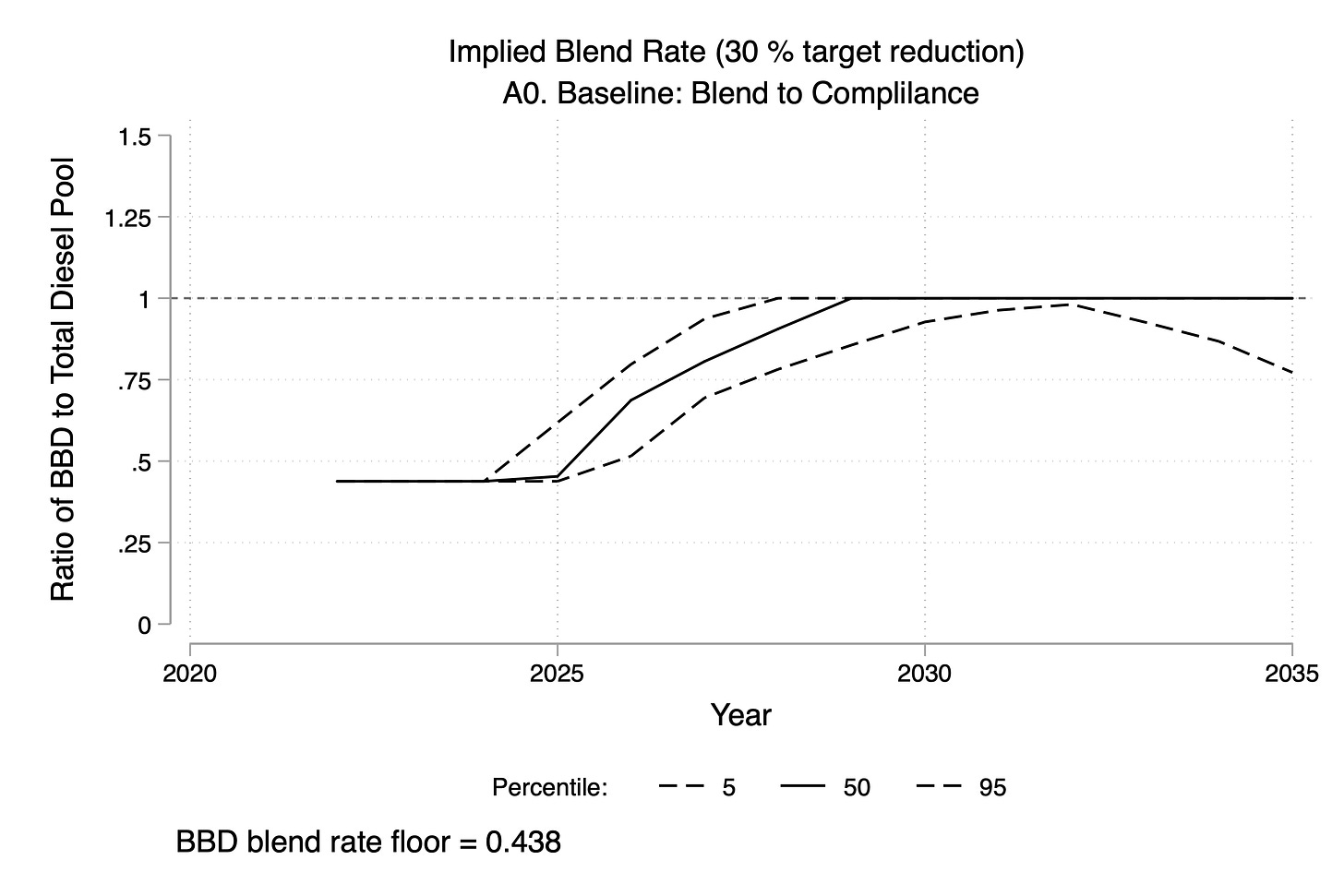

With these assumptions in place, we next calculate how much BBD would be needed to reach compliance with a new LCFS target of 30% CI reduction below 2010 levels by 2030. We assume that the percentage of BBD in the diesel pool does not drop below 2022 levels and that additional BBD will have to come from high-CI feedstocks such as soybean oil because low-CI feedstocks such as used cooking oils and animal fats are “nearly tapped out”.

By 2028, we project at least a 50% probability that the California diesel pool will have no petroleum. By 2032, there is almost a 95% probability of no petroleum diesel. The pressure to eliminate petroleum diesel may be relieved somewhat after 2032 if electric and hydrogen medium and heavy duty vehicles enter the fleet in the numbers predicted in the scoping plan. Electricity and hydrogen will likely have a lower CI than BBD, so introducing them would allow some BBD to revert to petroleum without exceeding the LCFS.

Altering our assumptions about the trajectory of other credit-generating fuels changes the probability that petroleum diesel disappears from the state, but all scenarios we consider produce a high probability that the vast majority of diesel is biomass based. This will create pressure on US agricultural markets as almost half of soybean oil is already used to produce BBD.

If the BBD blend rate hits 100%, further LCFS compliance must come from less price sensitive sources. The LCFS credit price is likely to return to the ceiling to reflect the scarcity of available credits from these sources. With petroleum diesel disappearing, gasoline will essentially be the only deficit generator, which means that gasoline suppliers will need to acquire expensive credits to achieve LCFS compliance---the cost of which will be passed along to consumers.

Postscript: This weeks article is cross-posted at the Energy Institute blog. I am now a faculty affiliate of the Energy Institute and will contribute to their blog regularly. Related, I have career news. I will be leaving UC Davis in July 2024 to start a position as a professor in Agricultural and Resource Economics at UC Berkeley. I will continue writing Ag Data News. I’m sad to leave Davis, but excited for new challenges.

If there was ever a geographic politically partition space to benefit from renewable high speed and local light rail powered by renewable would certainly be California. How fucking pathetic of the people and the government.

Democratic party constituents, if we’re still around after the next cycle, stay the fuck away from Gavin Newsom. He’s another Bill Clinton. A corporate socialist claiming he’s doing it all for “we the people” as we remain the proletariat

“For example, renewable diesel produced by co-processing soybean oil with fossil feedstock in a diesel hydrotreater at Chevron's El Segundo refinery using soybean oil transported by rail to California has CI of 51.74 grams of CO2 equivalent per megajoule of energy. That's a mouthful, and it illustrates the myriad ways that even renewable fuels can emit carbon. Petroleum diesel has a CI of 100.45, almost twice as large.”

This policy does nothing but shift the carbon footprint to the Midwest were corn and soy beans are produced. Equation used to arrive at these numbers is intentionally exclusive. It includes the transportation from the production site in the Midwest. What is not included is the entire footprint concerning the production of the commodity. How incredibly disingenuous. Just like ethanol which requires 5 quarts of gasoline to produce a gallon of this substance, nothing more than an industrial agrabusiness complex subsidy. Fucking pathetic