Hay, It's National Utah Day!

Yesterday, my Twitter feed informed me that May 31 is National Utah Day.1

Utah is known for its great salt lake, awe-inspiring national parks, skiing, the Mormon religion, and (to New Zealanders) the World's Fastest Indian. It is not well known for agriculture, but there is one way in which its agriculture is just like most other states.

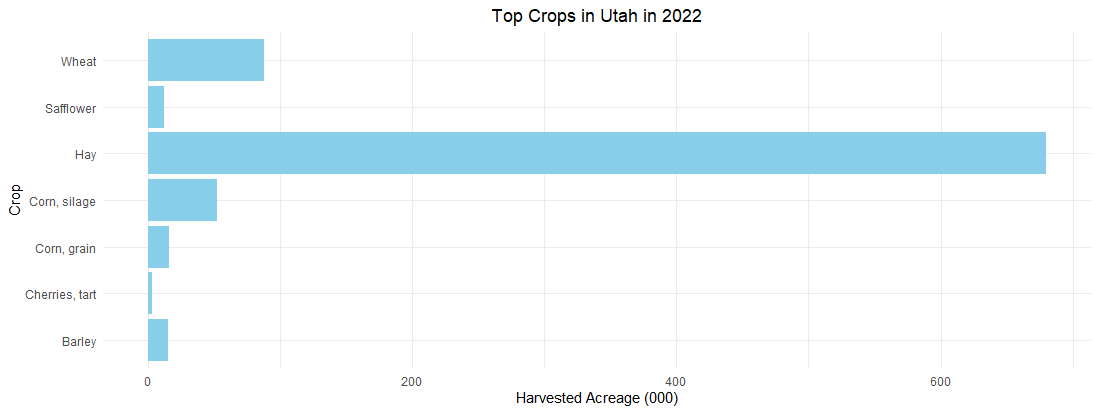

Utah agriculture is dominated by hay. In 2022, 80% of the harvested crop acres in Utah were hay.

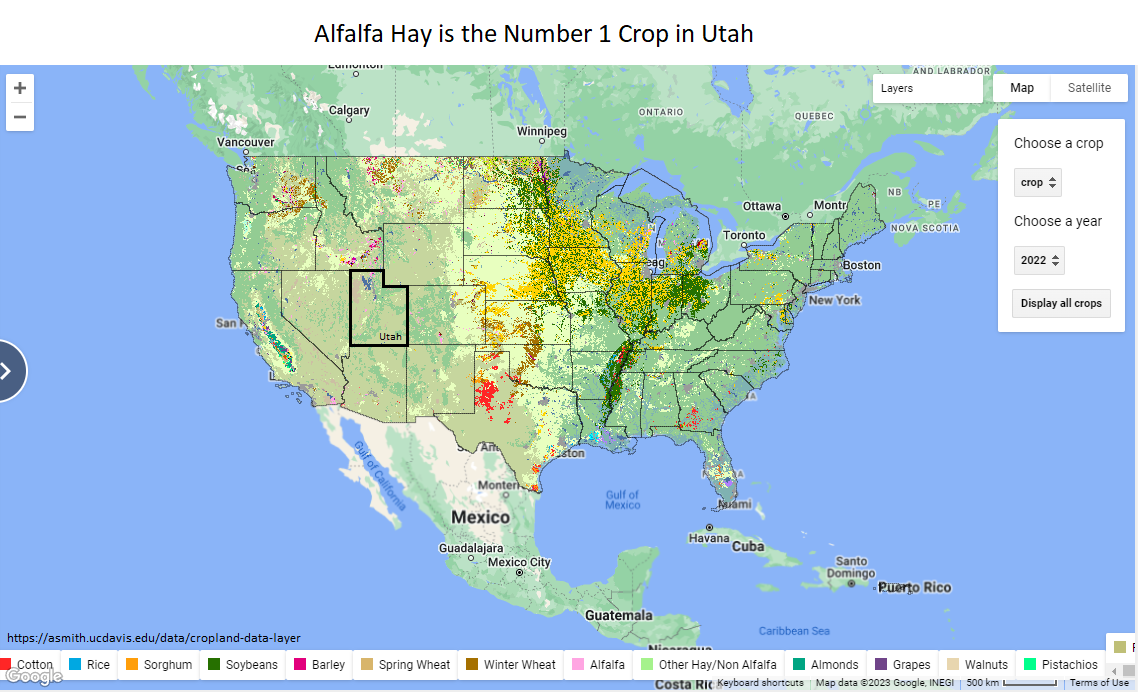

Two-thirds of Utah is federally owned and is therefore managed primarily for preservation, recreation, and development of natural resources. The largest area of agricultural production is in Cache County in the north next to the Idaho border. Pink areas in the map below indicate alfalfa hay. They are difficult to see because Utah, like many of its neighbors, has relatively little cropland.

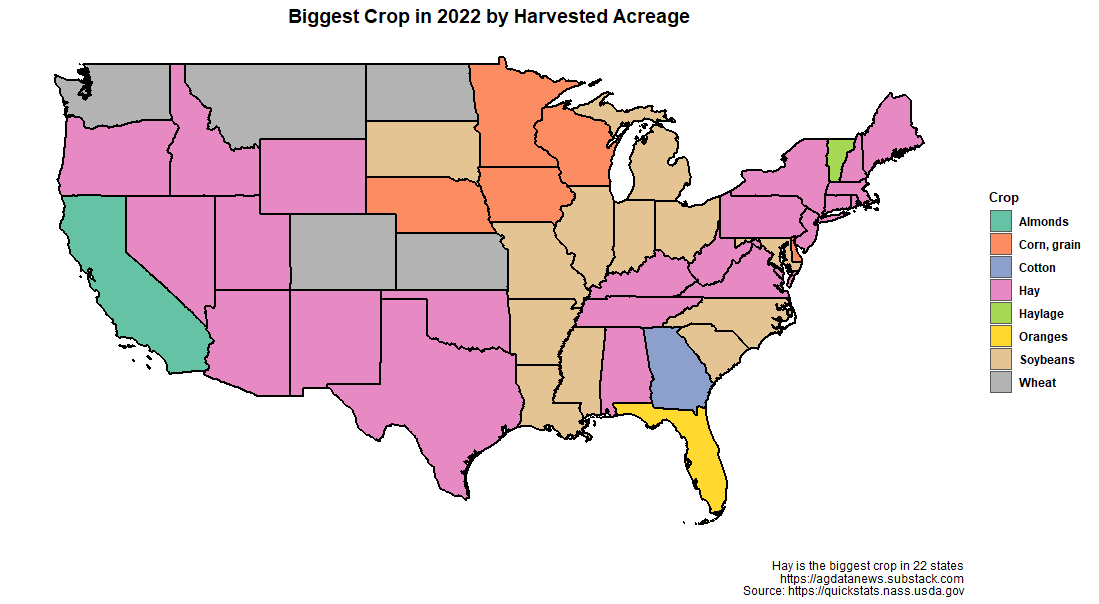

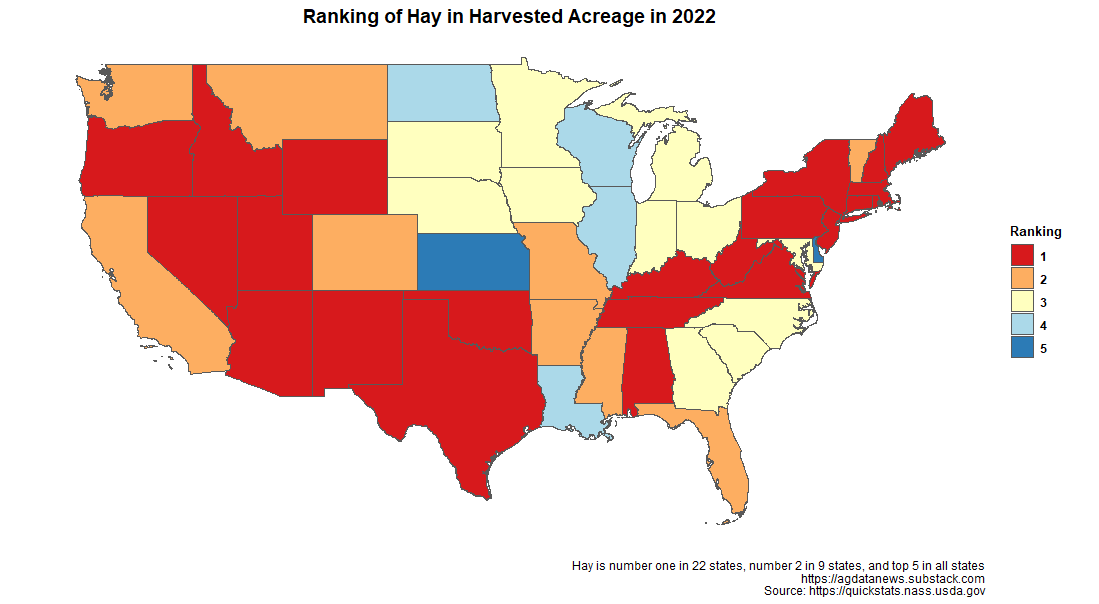

Utah is not unusual in having hay as its main crop by acreage. Hay is number 1 in 22 states in the lower 48, mostly those in the southwest and northeast. Intensive agricultural areas such as the Midwest, Washington and California tend to have other crops at number 1.

However, hay is in the top 5 in every state. It is beaten out by corn and soybeans (and sometimes wheat) in the Midwest.

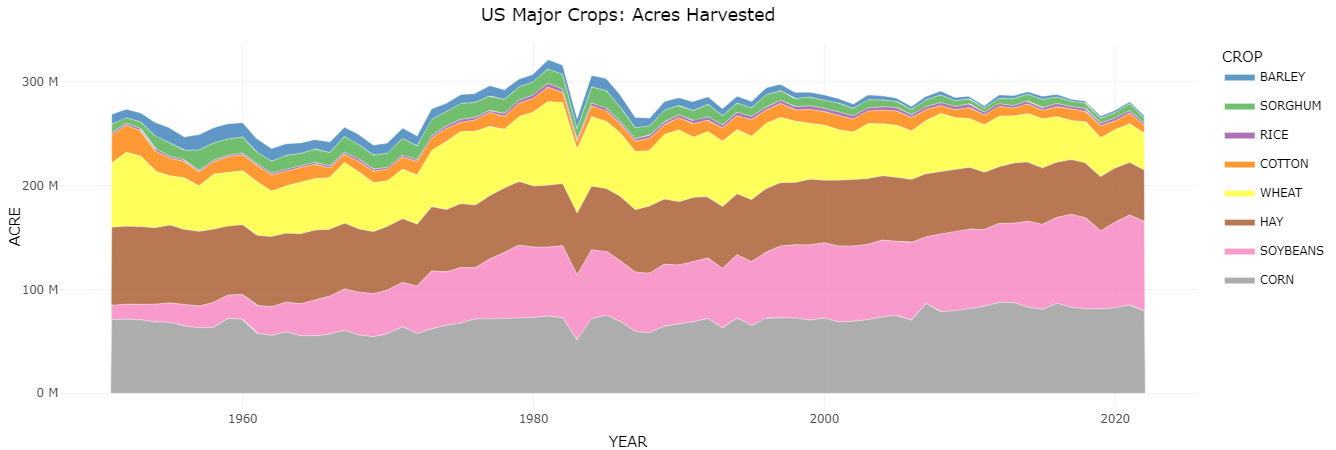

There were 49.5 million acres of hay in the US last year, which placed it third among all crops behind corn and soybeans. Hay was number one in the 1950s with 75 million acres, and it has been in third position since 1994. Soybeans has been number one in 6 of the last 8 years.

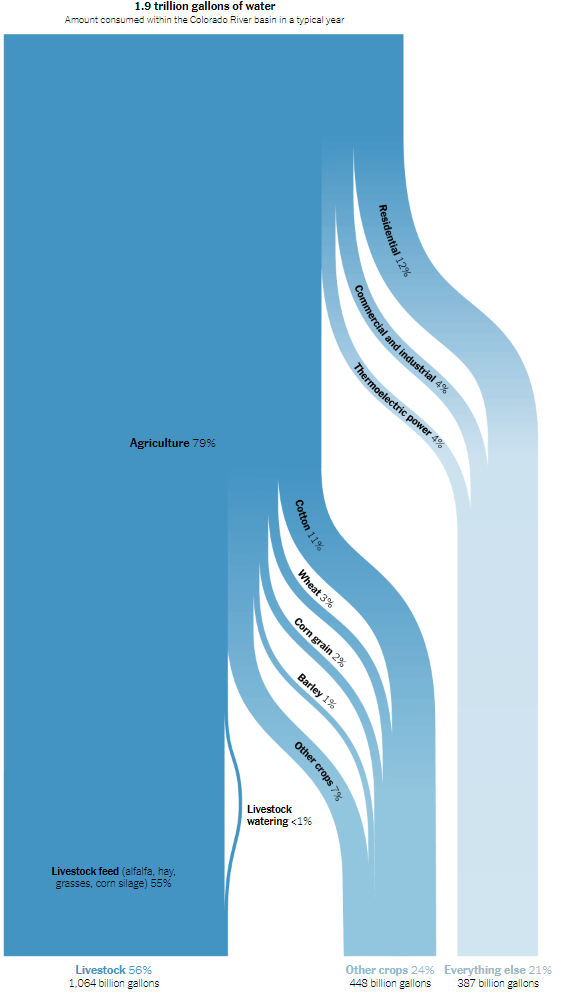

Hay has received a lot of attention recently based on the large amount of irrigation water it absorbs. The plot below from a New York Times article shows that most water from the Colorado River goes to produce hay to feed livestock.

The implicit claim in this figure is that we're wasting all our water on animal food.

There is some truth to this claim. Some locations overdraw groundwater aquifers, which reduces the future amount of water available for everyone. It is for this reason that parts of California's Central Valley are sinking, and it is why the state legislature responded in 2014 by passing the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA).

In addition, water is inefficiently allocated and priced in most places, so metaphorical dams prevent water from flowing to its most valued uses. Farmers grow alfalfa with cheap water because there's no way to get it to municipalities that would pay more for it.

If we were to stop wasteful hay production, the argument goes, then we could move the water to where it is most needed and people would have to reduce meat and dairy consumption.

This argument is overstated for at least three reasons.

If we raised the price farmers pay for water, market adjustments would mitigate the effects on meat and dairy consumption. The amount of mitigation would depend on how much consumers would reduce consumption in the face of higher prices. If consumers would not cut back much (i.e., they have inelastic demand), then raising water prices would not change consumption patterns much.

The capacity for livestock producers to shift rations towards other feeds such as almond hulls or corn would mitigate the effect on meat and dairy prices of making hay more expensive.

The inefficiencies may not be as great as you think, so removing those inefficiencies would not change outcomes as much as you think. In this paper, Nick Hagerty modeled what would happen if you made water freely tradable in California. He found that the economic gains would be relatively small. High profile cases like this one in Arizona suggest massive inefficiencies, but they maybe more anecdote than the norm.

There may be unintended consequences to removing agricultural water. In this paper, Muyang Ge, Sherzod Akhundjanov, Eric Edwards, and Reza Oladi examine the "United States’ largest ever agriculture-to-urban water transfer," which occurred in Southern California beginning in 2003. They find that, when farmers employed water conservation programs in response to the lack of irrigation water, the Salton Sea became a dustbowl creating substantial air pollution.

In short, there are places where growing hay may be inefficient, but overall hay is here to stay.

I made the bar chart and two maps using this R code. Other figures from our data apps.

A tweet from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) tipped me off on National Utah Day. They used the opportunity to highlight research conducted at Utah State University's Agriculture Experiment Station. NIFA is the part of USDA that funds research projects to "address key national and global challenges." If you do research in agriculture, NIFA is an important potential funding source.