This article was written by UC Davis ARE PhD students Gregory Boudreaux and Peter O’Brien. It is the first of several excellent articles written by students in my ARE 231 class in Fall 2023 that I'll be posting here.

Countries have imposed trade restrictions in times of distress throughout modern history. Whether to shore up domestic food stores or stabilize prices, policymakers often use trade export bans to calm domestic unrest. As of this writing, there are 19 countries with active food export bans, per the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). Most notably, India banned the export of non-basmati rice last July in response to concerns over rising prices. This action sent the UN FAO All Price Rice Index to a 12 year high in August, and inspired headlines such as “Why India's rice ban could trigger a global food crisis.”

These concerns are most acute for developing countries, where rice is a staple good and a key source of calories. To make matters worse, India’s export ban comes during a year of poor weather conditions for growing in Asia, the world’s largest rice producing region.

So, how worried should we be about these threats to global rice supplies considering this extreme climatic and policy environment?

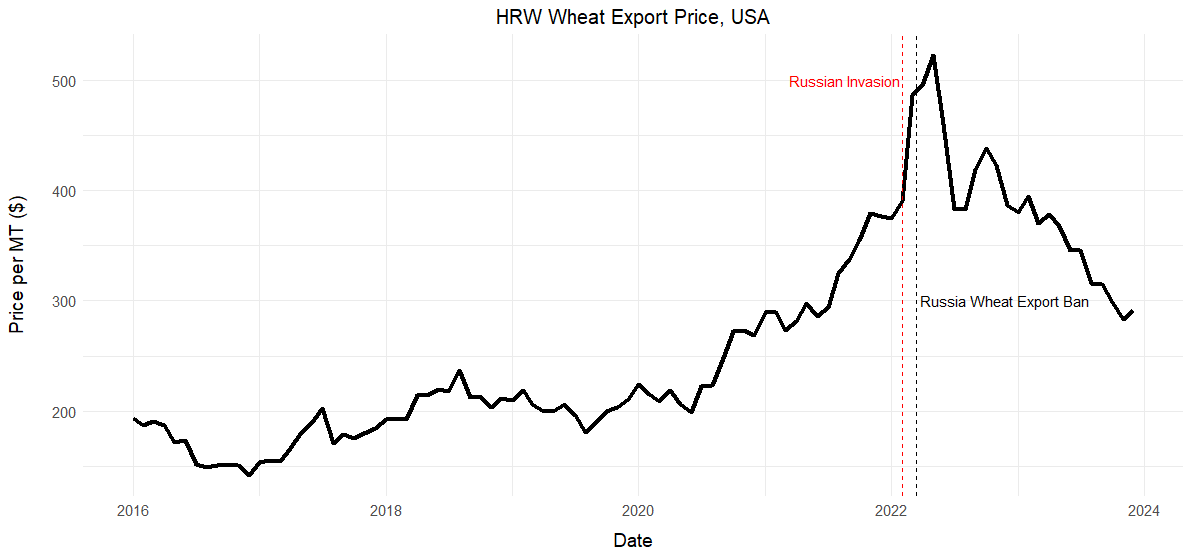

The volatility in global wheat markets in 2022 may provide a useful point of comparison. After Russia invaded Ukraine and sparked a war between two of the largest wheat producers in the world, headlines expressed concern about a global food crisis.

The figure below shows the trend in wheat export prices following the invasion. The spike in prices seen following the invasion makes it clear why many (but not all) experts were concerned about wheat shortages, and why some developing nations countries heavily reliant (such as Egypt and India) on wheat imports decided to ban wheat exports. Russia also temporarily halted their wheat exports for three months during the early onset of the conflict.

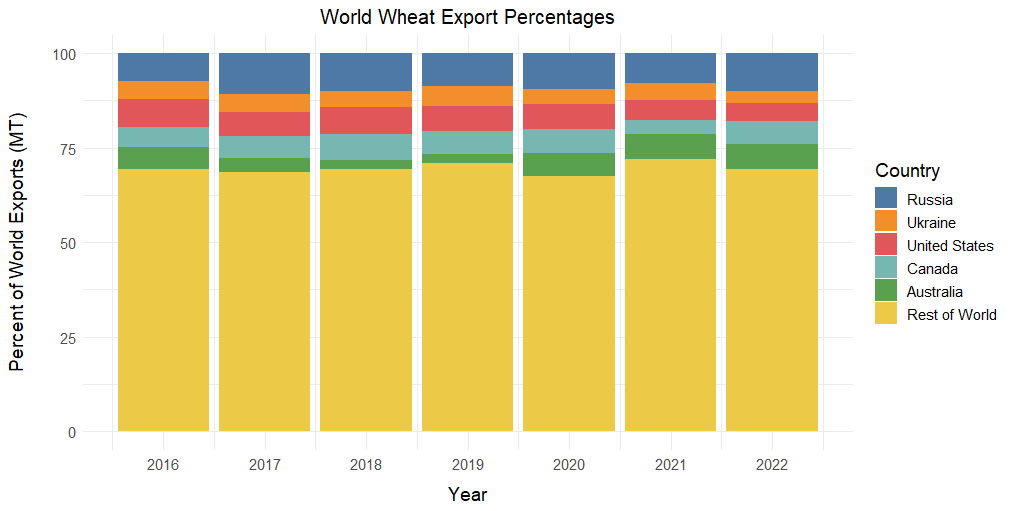

And yet, our worst fears were never realized. The final quarter of 2022 saw a steady decline in wheat prices, and that trend has continued through today. One reason for this decline is that other major exporters, like Canada and Australia, stepped in to fill the void with a bumper harvest in 2022. Russia and Ukraine are major players in world wheat markets, but they represent a relatively small proportion of total supply worldwide.

Based on data provided by the USDA FAS, Australia, Canada, and the EU—three of the five largest wheat exporting regions in the world—collectively increased their export tonnage by 25% in 2022. Australia alone increased the value of its wheat exports by over 6 billion dollars. In addition, an agreement was signed in July of 2022 to allow for the resumption of Ukrainian wheat exports via the Black Sea.

There are obvious similarities between the wheat crisis last year and the one in rice markets today. Both centered around the largest exporters of wheat (Russia) and rice (India). Both involved threats to production and the flow of international trade. At this point, it would be easy to conclude that the panic surrounding rice supplies is yet another overreaction, and that we simply should let world rice markets manage the disruptions, as they did with wheat. However, there are key differences between the two markets that could prove vital in their response both to the production and trade disruptions.

The affected countries in the wheat crisis represented a much smaller fraction of global wheat exports than the key players in the rice crisis today. India is the largest exporter of rice in the world by tonnage, providing roughly 25 to 40 percent of the world’s rice exports each year between 2018 and 2021. Vietnam and Thailand provide the next largest shares of world rice exports, and these countries’ ability to ramp up rice production will be a key determinant of the short-term impact of India’s rice export ban.

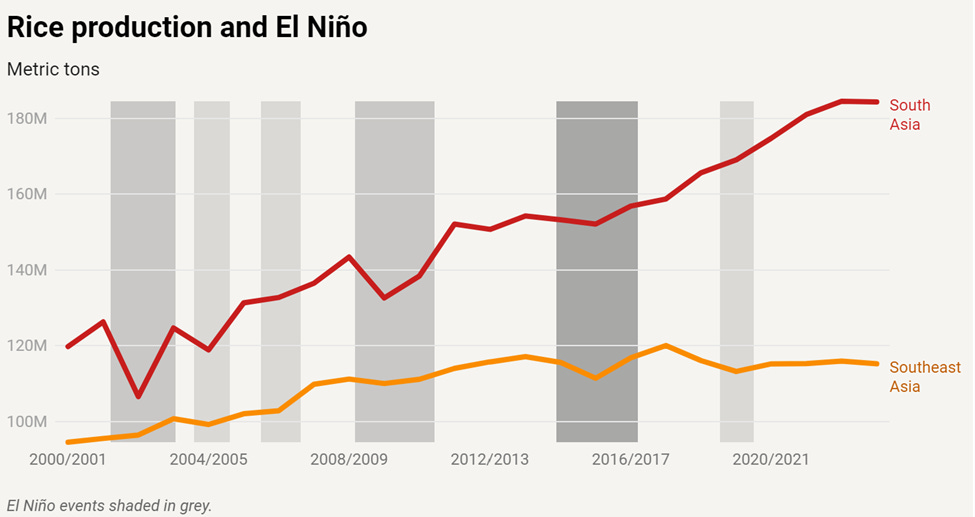

While the major wheat exporters are spread across multiple continents, the top five rice exporters are concentrated in Asia, making world rice production more vulnerable to localized shocks in this region. The current El Niño occurrence brings complicated weather patterns to this critical region of rice production, which threaten other top exporters’ ability to cushion the blow of India’s ban.

The figure below shows yearly rice production in both South and Southeast Asia, with historical El Niño events shaded in grey. The figure suggests that rice production declines during El Niño events. Early indications for 2024 rice production in Asia are not reassuring, as Thailand and Vietnam are both experiencing periods of drought. In response, Thailand’s government has urged rice farmers to reduce their acreage to conserve the country’s water reserves.

In the medium-term future, the extent to which this complicated web of trade distortions and weather shocks will affect prices and food security is uncertain. However, in the short term, impacts are already being felt and exacerbated by misguided policy responses in importing countries. For example, the Philippines, which recently overtook China as the world’s top importer of rice, has instituted a price ceiling for rice. Price ceilings are a blunt policy instrument that is well understood by economists to exacerbate shortages and reduce product quality. In fact, economist and former Philippines Finance Undersecretary was asked to resign after noting this stylized fact in a Facebook post.

The current situation in rice markets reveals that global trade shocks in concentrated export markets, and the ensuing domestic policy responses of importers, can have major implications for food security and resilience. The resolution of the 2022 scare in global wheat markets following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine revealed the benefits of both international cooperation and trade liberalization for smoothing the impacts of conflict. However, the differences highlighted above suggest that we can’t anticipate such a response in global rice markets today.

Market structure and geographical details can make all the difference.

We made the figures using this R code.