Beer Before Bread

The Wikipedia version of the origin of agriculture is that, around 12,000 years ago, people in the eastern Mediterranean started cultivating grains and legumes. Instead of migrating to wherever they could find food in the wild, they saved seeds and planted them in the same location year after year. Through seed selection, their productivity improved, they figured out how to make bread, and their crops were able to feed them year round.

The pioneering farmers had to figure out what to do with surplus production. One story is that they left mashed up grain in water and (perhaps accidentally) discovered that it developed into a mixture that resembles what we now call beer. I don't imagine it tasted very good by today's standards, but it was storable and high in calories. It also got people drunk, so they started making it intentionally.

There's another theory about the origin of agriculture.

In the alternate theory, ancient farmers started cultivating grains to make beer. Scholars have found ethnographic and anthropological evidence that ancient societies fermented grain and brewed beer at the time of the first crops. These societies often held large feasts, which were crucial for establishing political power. Scholars point out that early crops were unlikely to be productive or dependable enough to provide sustenance, but could have been used to make beer for feasts. They emphasize that early grains were likely better for brewing beer than baking bread, and that it took centuries after the beginning of grain cultivation to achieve the technology and seed quality required to reliably produce bread for food.

Some scholars estimate that 40% of cereal grain production in ancient Sumeria went into beer. In the modern United States, a similar percentage of corn is used to make alcohol, but that ethanol is consumed by cars rather than people.

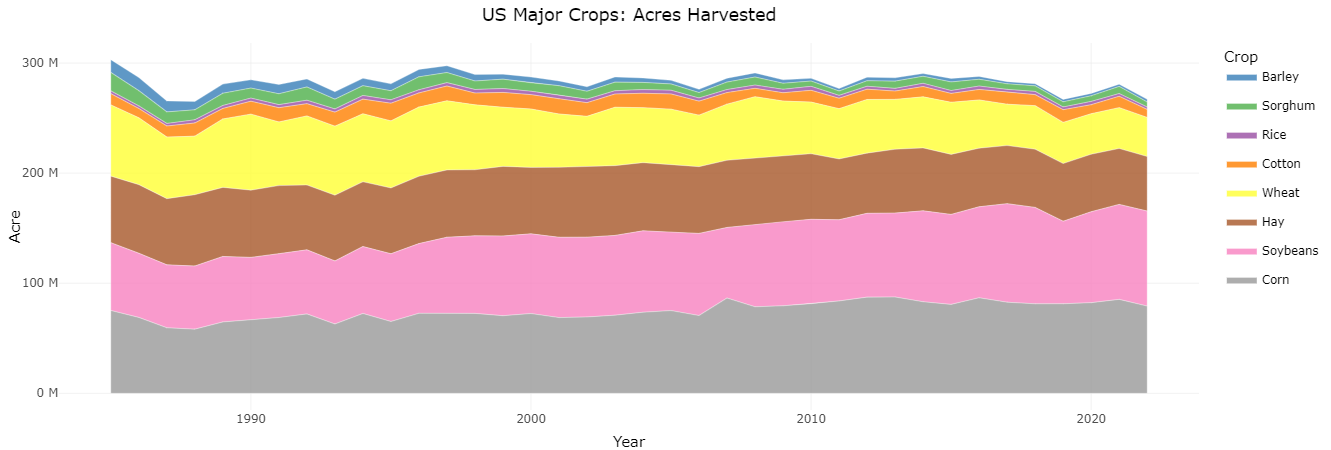

For human consumption, about 75% of US barley and about 10% of US rice is used for beer. (Anheuser-Busch is the largest user of American rice.) However, rice and barley are relatively small crops, each occupying about 2.5 million acres in recent years. Hops occupy an additional 55,000 acres.

In total, the ingredients for beer use less than 1% of US cropland. Wheat, most of which is used for bread, uses 15 times as much land as beer. Corn and soybeans each use 35 times as much as beer, and hay uses 20 times as much. These crops are grown mostly for animal feed and automotive fuel.

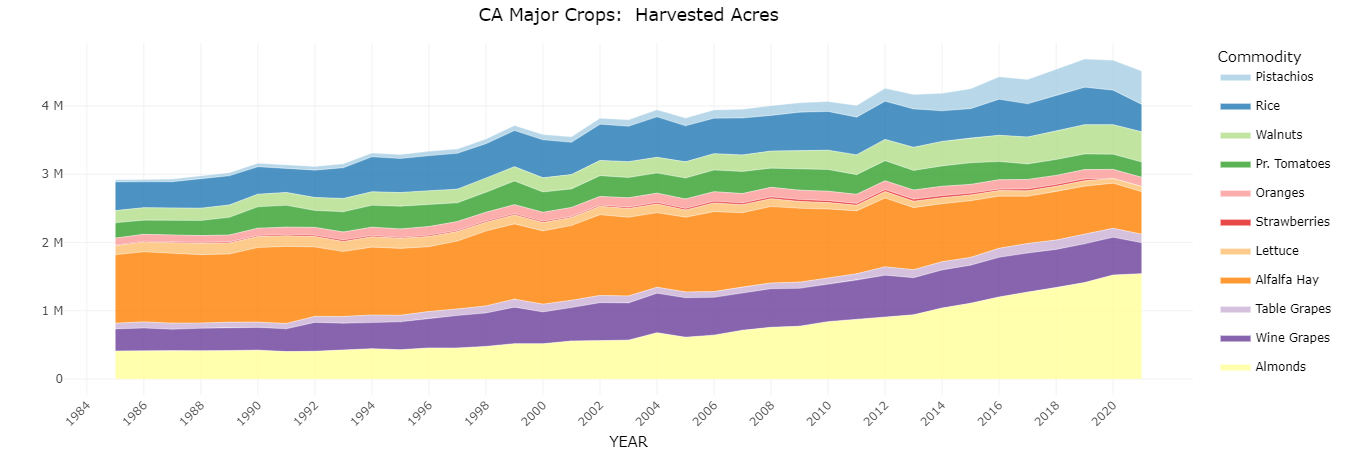

In California, alcoholic beverages are a larger part of agriculture. Wine grapes grow on about 500,000 acres in the state, or about 10% of cropland.

I learned about the "Beer Before Bread" theory from the fascinating book Drunk by Edward Slingerland. (Here is a New York Times review of the book. I learned about the book from the Offline podcast.)

Slingerland asks why alcohol is such a prominent part of human societies, both now and throughout history. Alcohol's prominence is a puzzle given that it is poison. Our bodies work to get it our of our system as quickly as possible. Moreover, large numbers of lives are destroyed every year by drunkenness through driving under the influence, sexual assault, alcoholism, and more. Why did natural selection not evolve us away from alcohol? Is our love for alcohol an evolutionary mistake?

Using a wide array of evidence, Slingerland argues that alcohol persisted because it gave societies a competitive advantage by promoting creativity, trust, and cooperation.

The feasts fueled by the beer produced from early crops were more than just parties; they were critical to building trust and cooperation. Alcohol suppresses the prefrontal cortex, which is the executive suite in our brain where planning and rational decision making happen. Suppressing it allows brain connections that promote creativity, and it makes people more willing to socialize with and to trust others. All successful business deals require trust.

As neither a historian or an anthropologist, I'm not qualified to assess Slingerland's case, as compelling as it seems. As an economist, however, this theory evokes familiar themes.

Alcohol is a technology that produces benefits to the drinker (taste, feeling of drunkenness, new connections), but it also produces both positive and negative externalities. By promoting creativity, trust, and cooperation, it can benefit people who become friends or business partners with the drinker, or those who buy the resulting creations. These are positive externalities. It has negative externalities because drunk people can harm others (and also their future selves).

Moreover, the internal and external effects of alcohol vary markedly across individuals and settings. People prone to alcoholism and their families experience much greater negative effects than others. Slingerland writes about the social benefits of drinks with 2-4% alcohol consumed in a social setting; drinking 80-proof whiskey home alone would not have those benefits.

Many technologies have similar characteristics. Large language models and other forms of AI promise large and variable benefits and costs for society. Agricultural technology has enabled cheap food, which is a boon to consumers everywhere, but has left many people and places with environmental damage and poor health. Smart phones give ubiquitous access to communication and information, but they may worsen mental health and cause accidents by distracting people. (Don't text and drive!)

We need serious analysis to inform smart policy in these complex settings, encouraging positive effects, discouraging negative effects, and avoiding the worst outcomes. There are a lot of interesting research topics here for enterprising scholars.

PS. I drank a beer while writing this article. It may or may not have made it better.

This comment is simple speculation.

If you think about how fermentation was discovered, it seems reasonable to think that an amount of some grain, possibly stored for future use, got wet and, being contained in some vessel, fermented. That presupposes that the grain was intended for a different use. If that is true, bread came before beer.