Environmental Outcomes of the US Renewable Fuel Standard

In December 2007, President George W. Bush signed the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS2) legislation, essentially mandating that an area the size of Kentucky be used to grow corn to make ethanol for transportation fuel. It is called RFS2 because it followed on the heels of 2005's RFS1.

Under the RFS2, the amount of ethanol used in the US has tripled. Since 2013, about 10% of essentially every gallon of US gasoline has been ethanol made from corn.

To qualify as a renewable fuel in the RFS2, corn ethanol needs to have 20% lower greenhouse gas emissions than gasoline. The statute also requires reviews every three years of the effects of RFS2 on environmental issues such as "hypoxia, pesticides, sediment, nutrient and pathogen levels in waters, acreage and function of waters, and soil environmental quality."

On Monday, my co-authors and I published a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences arguing that additional corn ethanol does not reduce carbon emissions once you account for changes in land use. It also has serious effects on nutrient levels in waters. This paper was the product of several years work led splendidly by Tyler Lark and an excellent team of researchers across several universities.

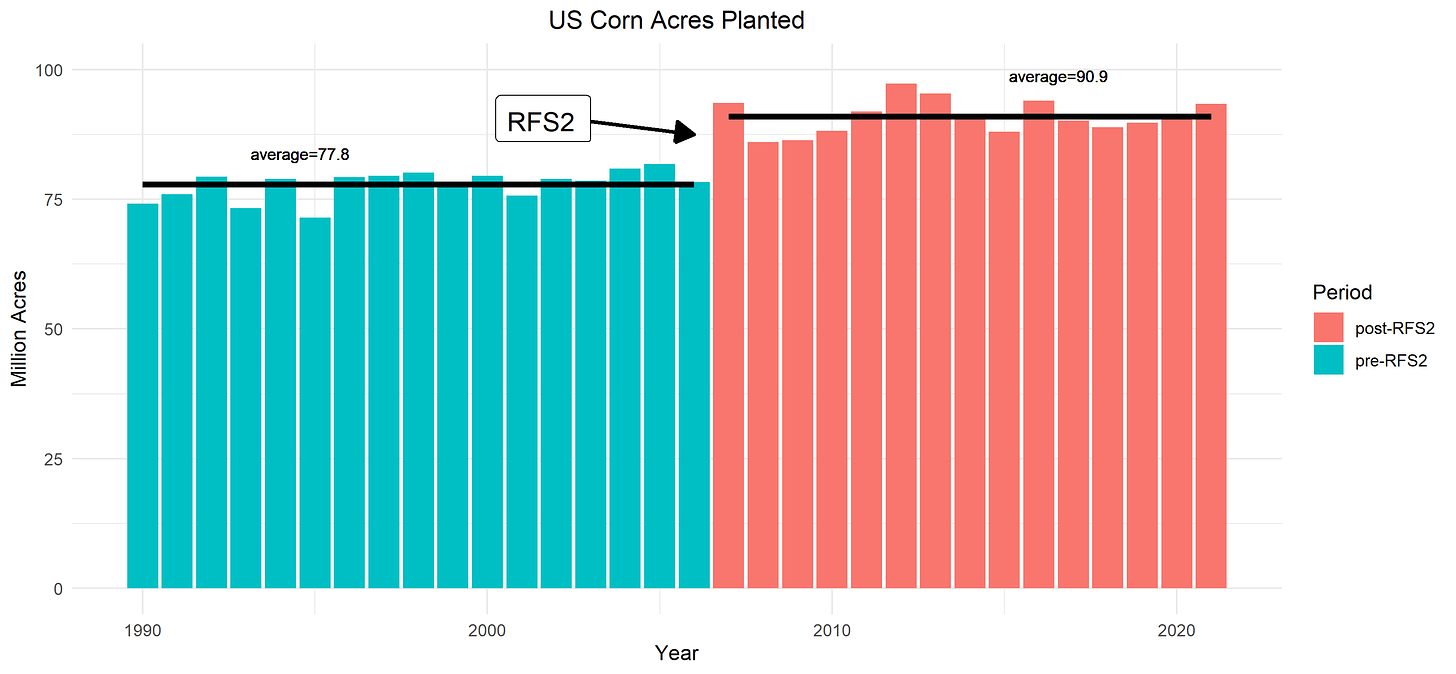

Before getting to the paper and the complexities of the modeling, let's look at some data. At the end of 2006, in anticipation of RFS2, there was enough ethanol production capacity under construction to more than double production. This construction boom cause corn prices to jump in anticipation of a forthcoming demand increase. Farmers responded by planting more corn beginning in 2007 and every year since. Here's your prima facie evidence that the RFS2 increased corn acreage.

More corn means more nitrogen fertilizer and more land converted to crops, which in turn increases greenhouse gas emissions and water pollution. Our modeling estimates how many more corn acres we had post-RFS2 compared to what we would have had without the RFS2. Estimating the "what we would have had," or business as usual, is the hard part.

Once we have estimated the incremental corn acreage and where it is occurring, then we can estimate greenhouse gas and water pollution effects.

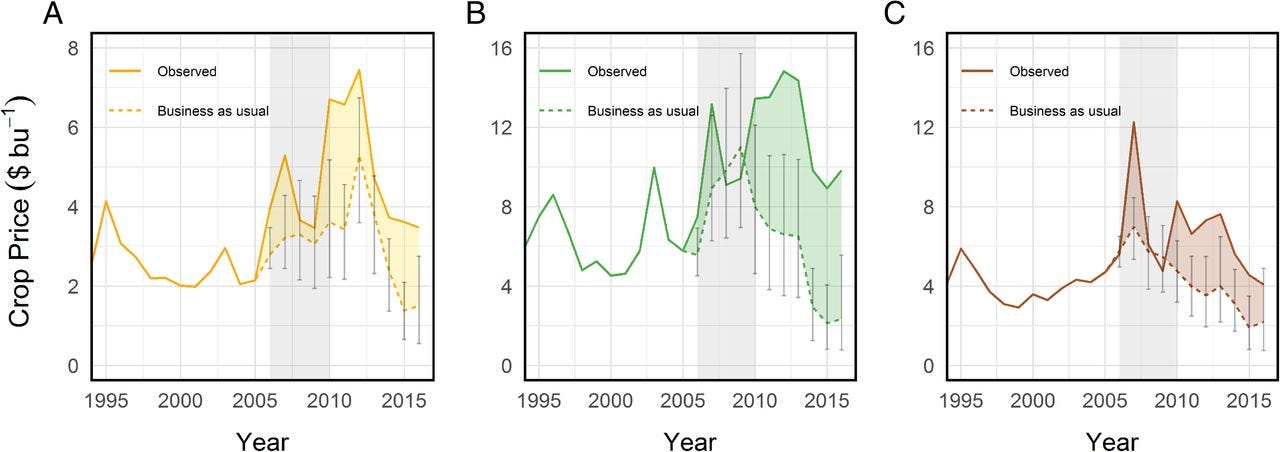

Using the same approach as in my 2017 paper with Colin Carter and Gordon Rausser, we estimate that the RFS2 raised corn prices by 30%, and soybean and wheat prices by 20% relative to business as usual. Business as usual prices increased in 2007-2010, but the RFS2 caused actual prices to increase by even more.

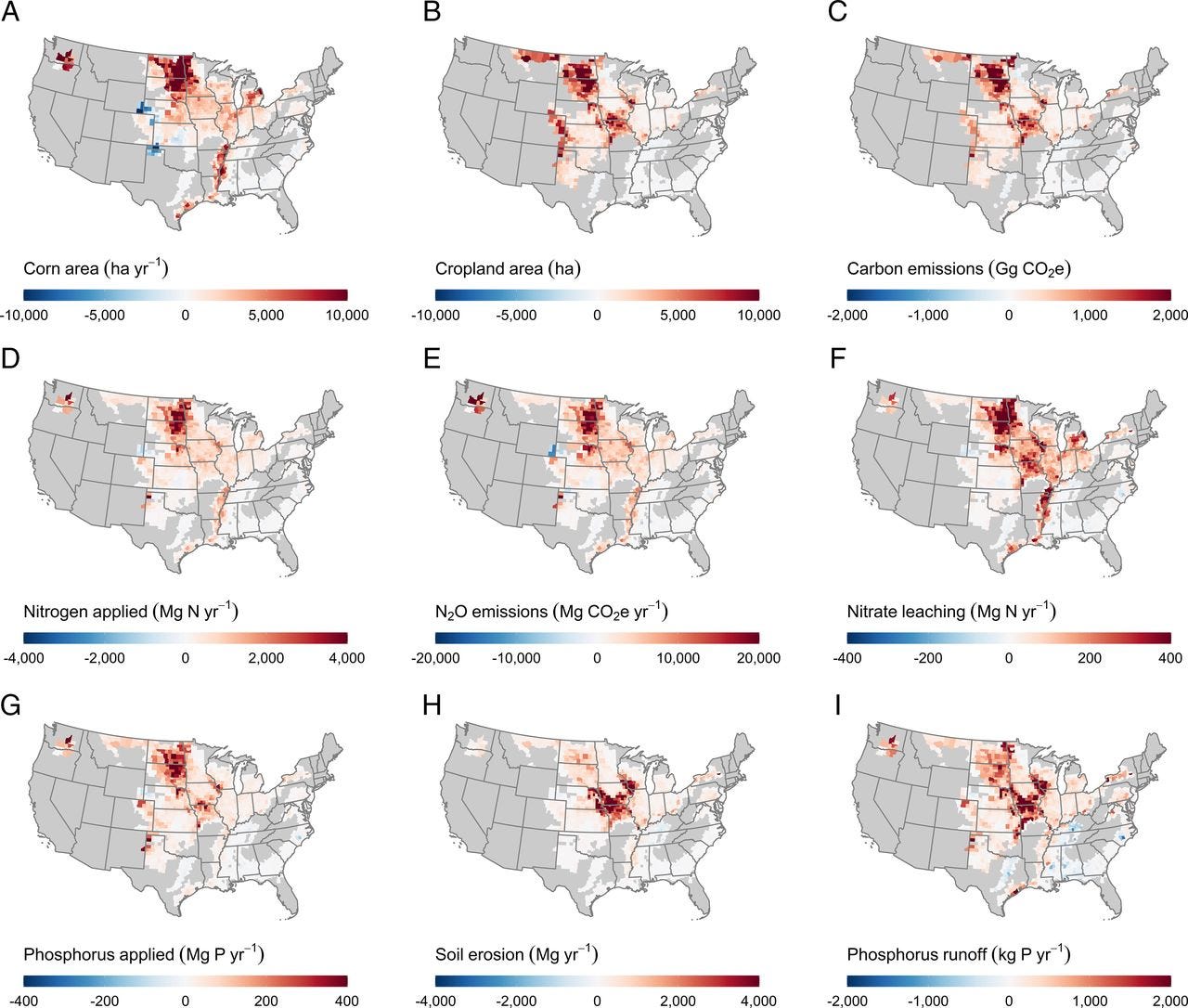

Using field-level data collected by satellites and point-level data from USDA's National Resources Inventory, we estimate how farmers' planting decisions responded to price changes in the pre- and post-RFS2 periods. Farmers in some regions were more responsive than others. The most responsive region was the prairie pothole region of the Dakotas and Minnesota. This region had the largest estimated corn acreage and cropland increases.

We estimate that the RFS2 expanded US corn cultivation by 6.9 million acres and total cropland by 5.2 million acres. This is larger than the 3.1 million post-RFS increase in planted corn acres because in the absence of RFS2, corn acres would have declined due to yield increases (more corn from less land) and increased demand for soybeans (more land for soybeans would mean less for corn).

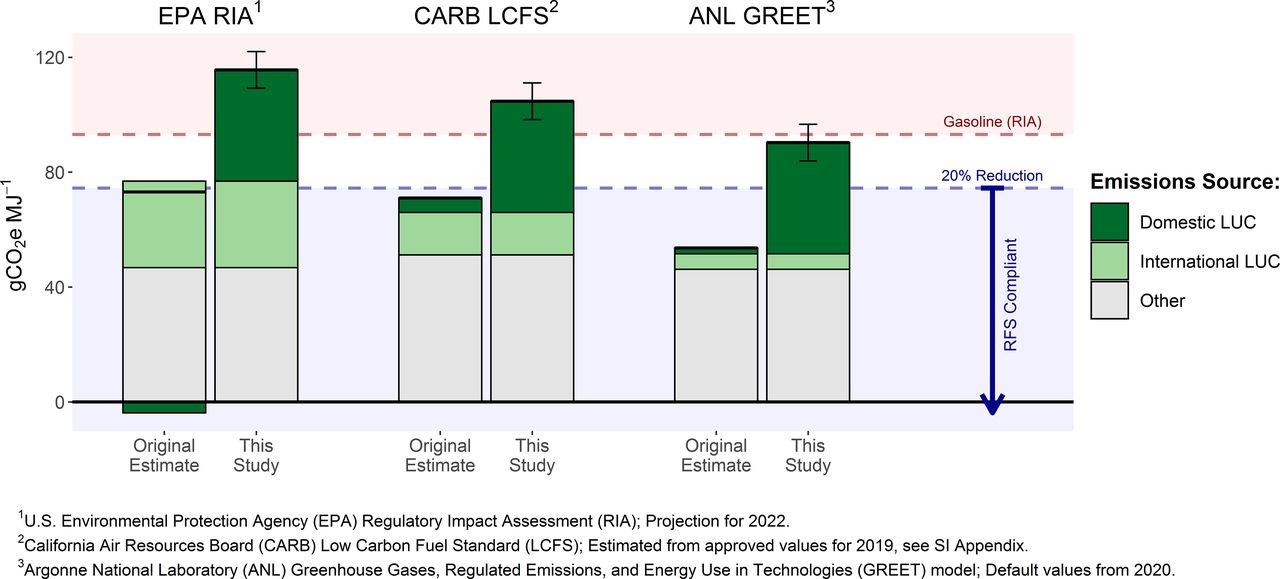

About 62% of our estimated increase in greenhouse gas emissions is from cropland expansion (513/831 gCO2e/L). When new cropland is cleared, the loss of biomass and disturbed soils create a large one-time emission of carbon. A further 15% comes from foregone abandonment of cropland, and the remainder is due to nitrous oxide emissions from increased fertilizer use.

When we add our estimated land use change emissions to other sources of emissions from ethanol, we find that ethanol is worse for the climate than gasoline. Previous studies were projecting into the future, so they relied heavily on modeling. We have the benefit of hindsight, which enables us to see how actual land use has changed. We do need to model what land use would have been like without the RFS2 (business as usual), but our findings are driven by actual land use patterns in the United States.

The genie is out of the bottle. The RFS2 forced ethanol into the system, but now it is a relatively low-cost source of octane and supply chains are set. Ethanol would stay at 10% of gasoline in the medium term if RFS2 went away. But, this research implies that expanding ethanol mandates in the future would be unlikely to provide climate or environmental benefits.

The only funding I received for this project came from the National Wildlife Federation. Their grant paid my salary for one month in the summer of 2017, and it paid for a graduate student research assistant to help with data analysis. We had complete autonomy in our work and felt no pressure to come to any particular conclusion.