Who is Responsible for "Responsible AI"?

Since ChatGPT burst onto the scene in November 2022, it seems everyone has been talking about the role of AI in society. The discourse has focused narrowly on generative AI, i.e., algorithms that generate text, images or video. People are concerned that generative AI will increase cheating in school or produce inaccurate or misleading information.

However, AI encompasses much more than content generation. The agriculture and food system faces numerous big challenges including poor air and water quality, climate change, labor scarcity, and deteriorating human health. AI offers potential tools to meet these challenges.

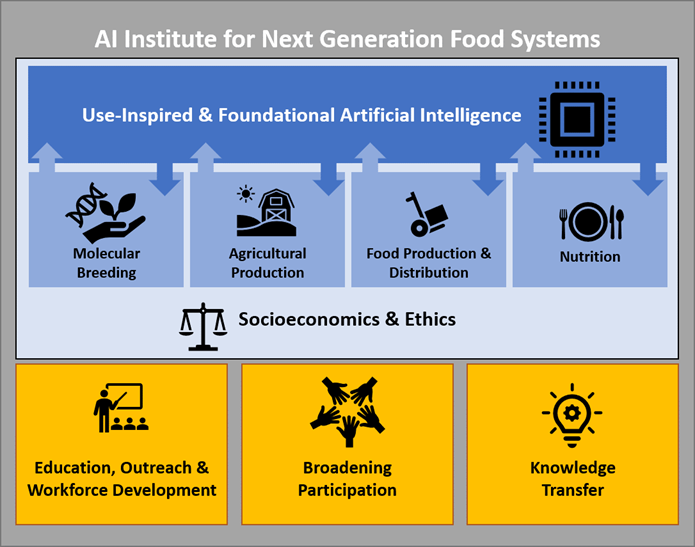

For the past three years, my colleagues at the AI Institute for Next Generation Food Systems (AIFS) have been working on AI tools to develop high-quality foods, increase agricultural yields, reduce resource consumption and waste, deliver highly traceable and safe food, assess the nutritional contents of a meal, and much more.

I lead the Socioeconomics and Ethics group at AIFS. Our ethics work is driven by postdoctoral scholar Carrie Alexander. Last week, Precision Agriculture published a paper Carrie wrote with me and Mark Yarborough that asks the following question: who is responsible for responsible AI?

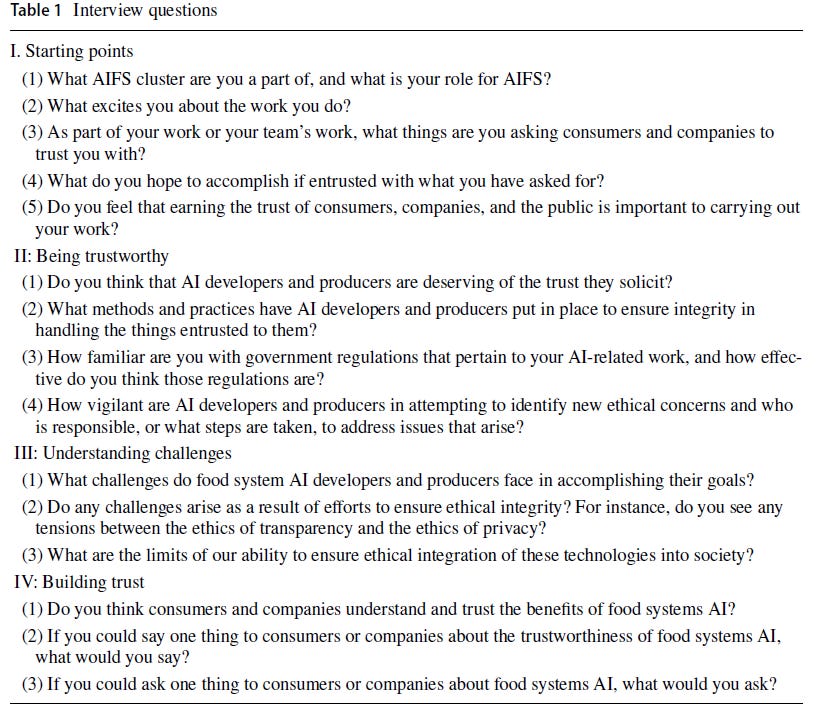

The paper reports the perspective of researchers on this question. Carrie interviewed about three quarters of the researchers in AIFS. Participation in the interviews was voluntary and strictly confidential to encourage meaningful and honest reflection. The interviews were conducted on Zoom and lasted an average of 45 minutes.

Interviewees expressed a strong sense of responsibility and ownership for the outcomes of their work. They conveyed a general sense that although oversight of AI technology development is needed, it is not clear what group or entity should be responsible. They generally had more confidence in academic research outcomes and practices, but pervasive doubt regarding the safety and ethics of commercial technologies.

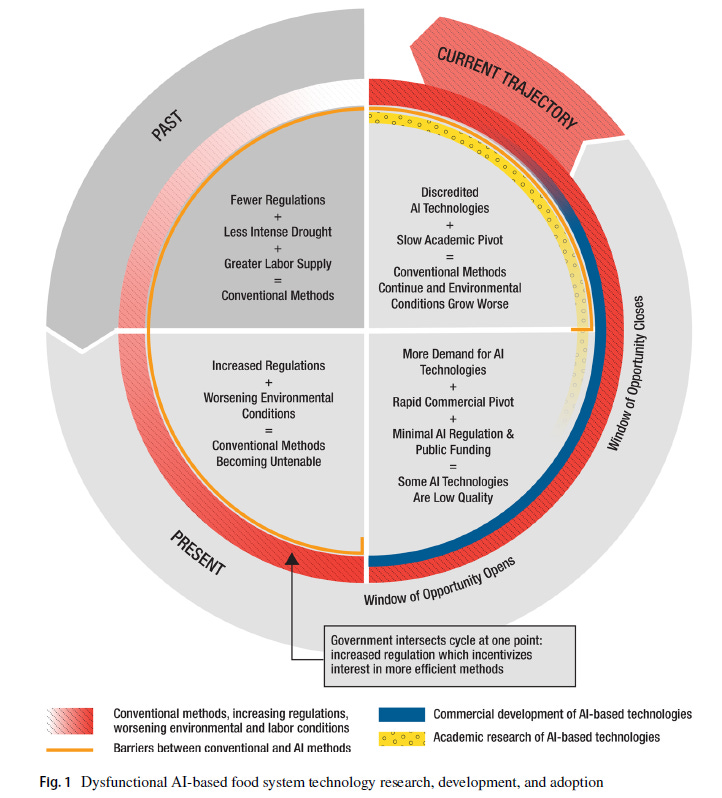

The interviews illustrate a dysfunctional system in which researchers see windows of opportunity for AI tools to help meet agriculture and food's big challenges, but numerous barriers to realizing that outcome.

Academic researchers face strong incentives to publish new discoveries, whereas commercial AI developers are incentivized to develop products to meet market demand. Solving the big challenges facing agriculture and food requires a lot of things the market won't demand. In economics jargon, we can't expect the private sector to solve the externality problem.

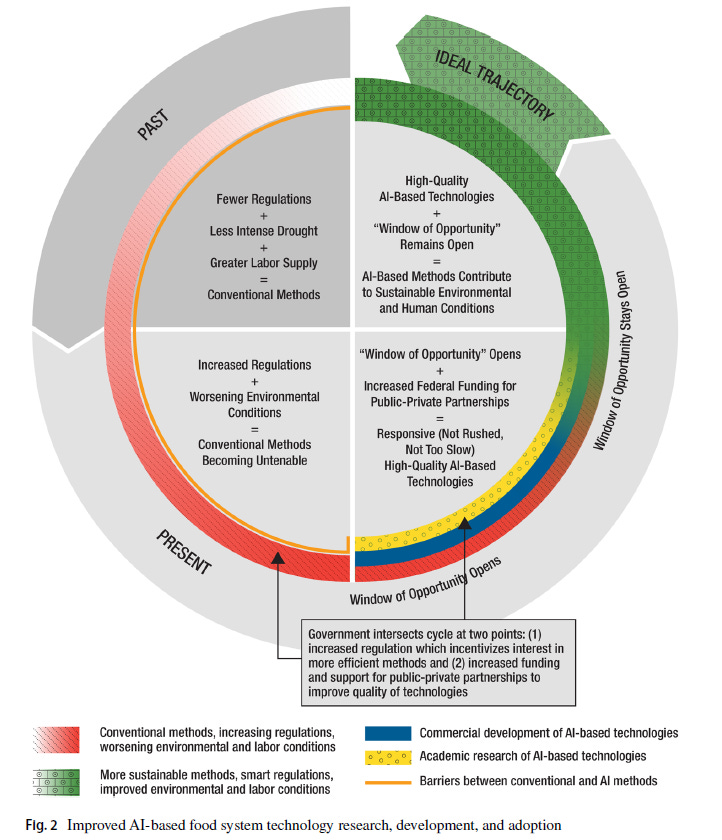

This is where we need the public sector, and it is where academic researchers can contribute. Public funding of AI research should focus on developing technologies that will mitigate negative externalities while increasing productivity and lowering costs (e.g., robotic weeding, nitrogen-fixing corn, precision irrigation). Farmers will adopt these technologies if they solve the problems they face (e.g., scarce labor, high costs), and public investment can direct those technologies so they also produce environmental and other societal benefits. Work with the private sector rather than trying to compete against it.

One way to have a future in which AI benefits society is to deliberately choose to develop beneficial AI tools. Fund projects directed at big challenges such as poor air and water quality, climate change, labor scarcity, and deteriorating human health.