Which Sweetener is the Best?

People like sweet things. Our bodies are programmed to gorge them because there's no better source of immediate energy. We take it in multiple forms, including high-calorie products like sugar and high-fructose corn syrup, and zero-calorie products like aspartame and sucralose. Many of us consume too much of it.

How do the various sweeteners affect taste? To answer this question, my daughter and I decided to re-enact the Pepsi Challenge. In the 1970s, Pepsi marketing consultants asked people to taste Coke and Pepsi without knowing which was which and to say which was their favorite. We blind-tasted various Coke and Pepsi products with different sweeteners and rated them. In contrast to our chicken sandwich and milk-substitute taste-offs, we mostly agreed.

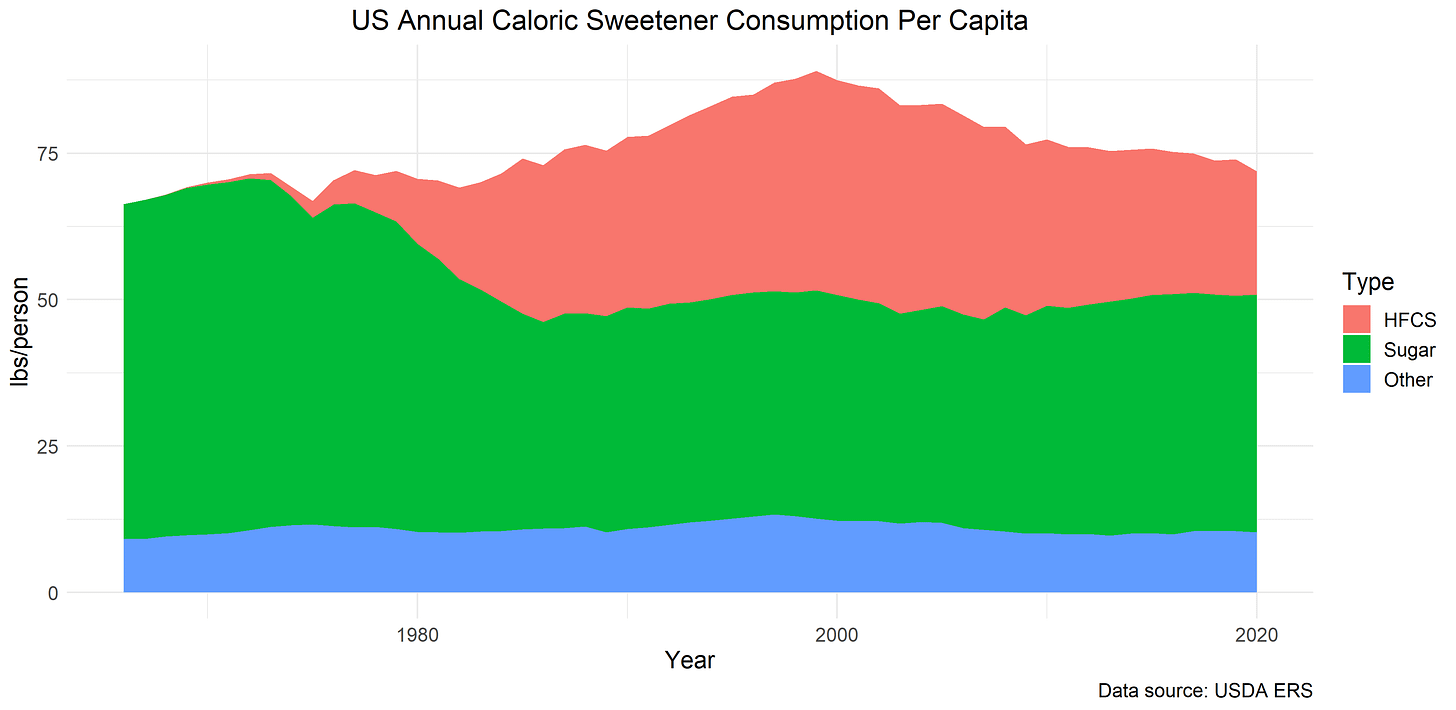

The average American consumes 73 pounds of caloric sweeteners per year, or about 22 teaspoons per day. This is 2-4 times what the American Heart Association recommends for good health, and it amounts to 350 calories per day. Just over half of this sweetener comes from sugar, 30% from high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), and the remainder from other products such as glucose syrup, dextrose, and honey.

US caloric sweetener consumption increased throughout the 1980s and 90s, reaching a peak of 89 lbs per person in 1999. It has since declined by 18%, and is now back to 1985 levels. Most of the decline since 1999 has been in HFCS, enabled in part by the rise of artificial sweeteners.

The caloric sweetener consumption data come from the Economic Research Service of USDA, which takes the quantity of sweetener supplied by food producers and importers and deducts 41% to account for food that is lost due to spoilage or uneaten portions. See here for more on loss adjustments to food availability.

Most of the HFCS is 55% fructose and half sucrose, very similar to sugar, which is 50% fructose and sucrose.

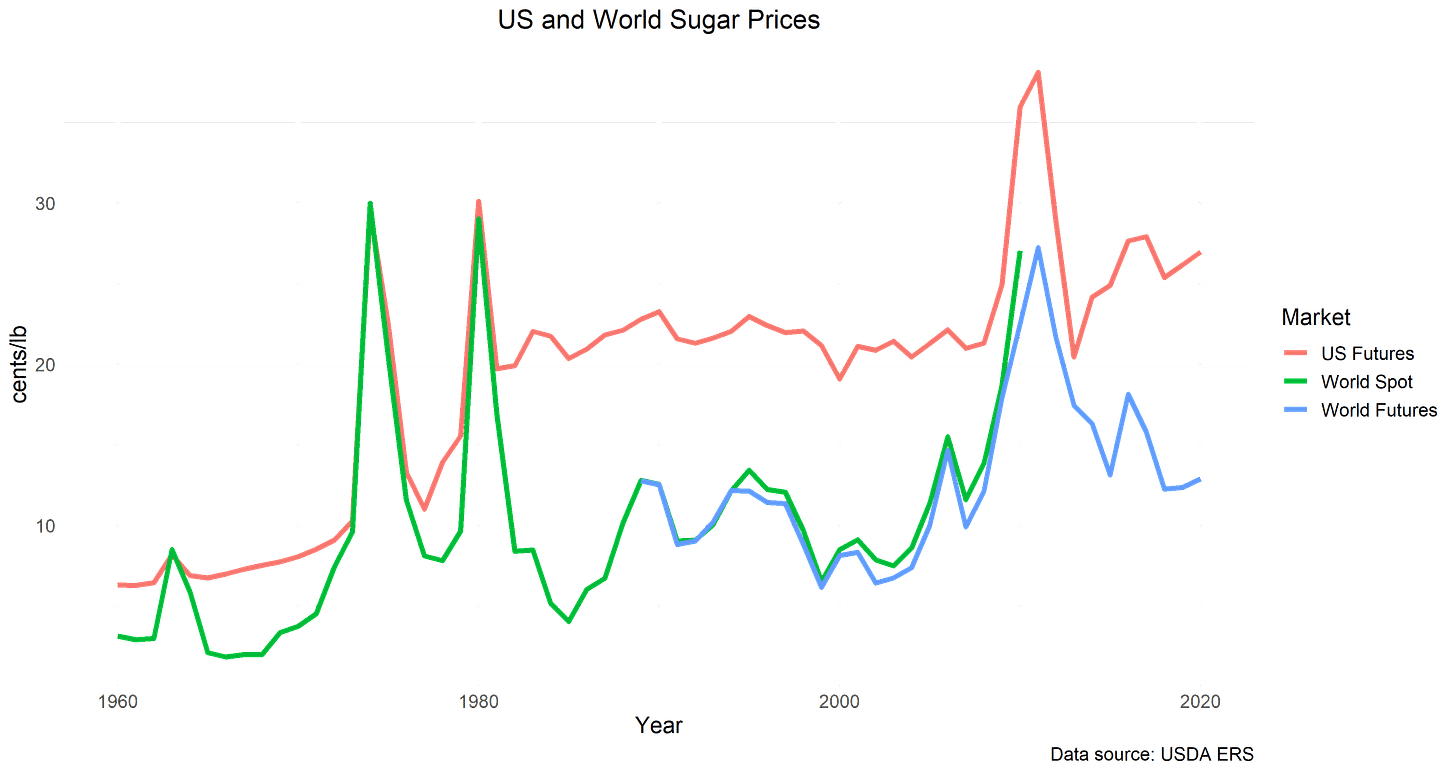

Americans consume much more HFCS than the rest of the world because of government policies that make sugar expensive. These policies have three components.

To keep the price high, USDA guarantees a minimum price to sugar processors, which in turn pay high prices to farmers. The prices for 2020-24 are 19.75 c/lb for raw sugar, and 25.38 c/lb for refined beet sugar.

To prevent over-supply at these high prices, USDA sets allowable production to 85% of estimated demand and assigns to each processor the maximum amount they are allowed to produce.

To prevent cheaper imports, the US imposes a tariff rate quota, which permits a small quantity to be imported duty free and then imposes a large tariff on imports above the quota. The current out-of-quota tariff is 15.36 c/lb for raw sugar and 16.21 c/lb for refined sugar.

The sugar program has taken this form essentially since 1981. Coke and Pepsi switched from sugar to HCFS around the same time.

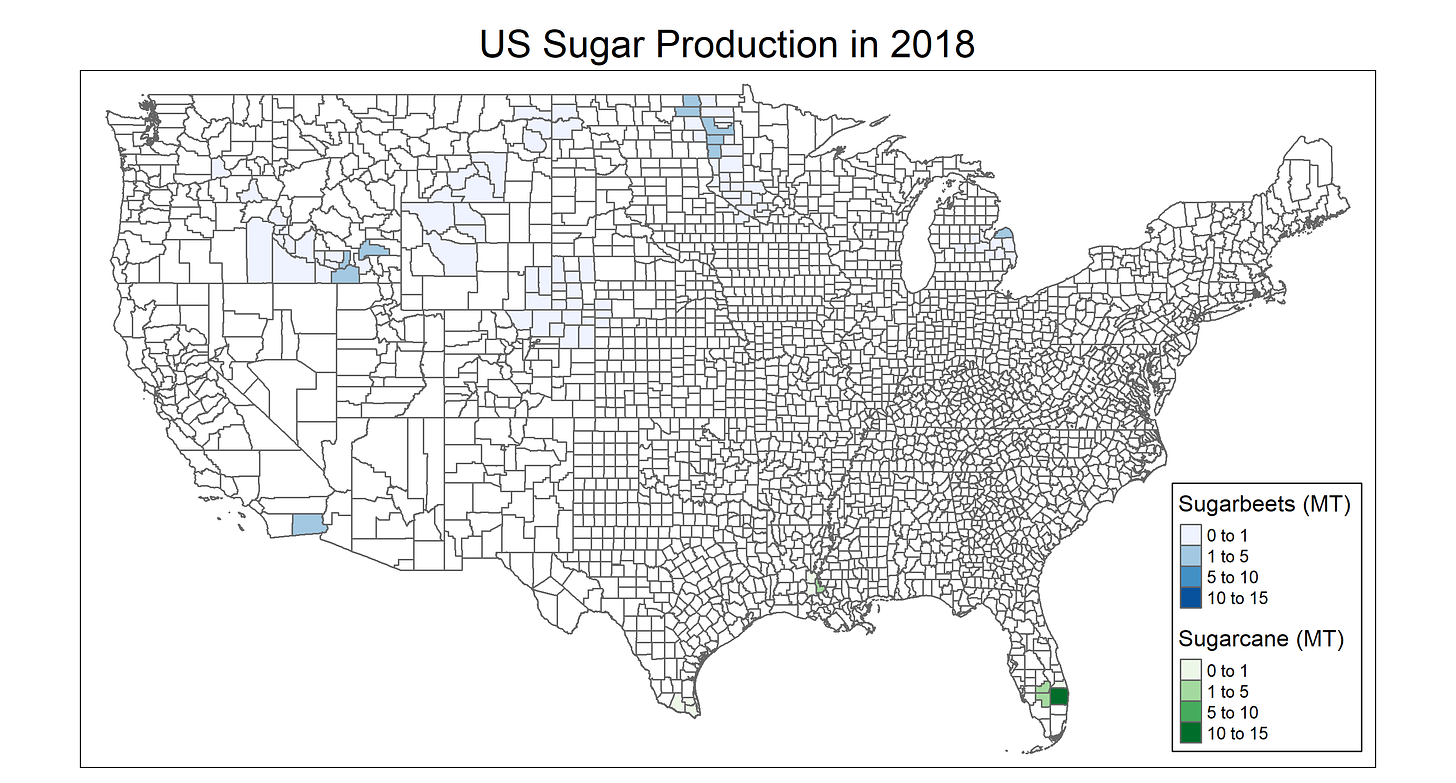

Half of US sugar comes from sugarcane and the other half from sugarbeets. Florida, Louisiana, and Texas produce all the sugarcane, with Florida the largest producer. Hawaii stopped producing sugarcane in 2017. Sugarbeets are produced in a larger number of states, with Minnesota the largest producer, followed by Idaho, North, Dakota, and Michigan.

So, does it matter whether your food is sweetened with sugar, HFCS, or something artificial?

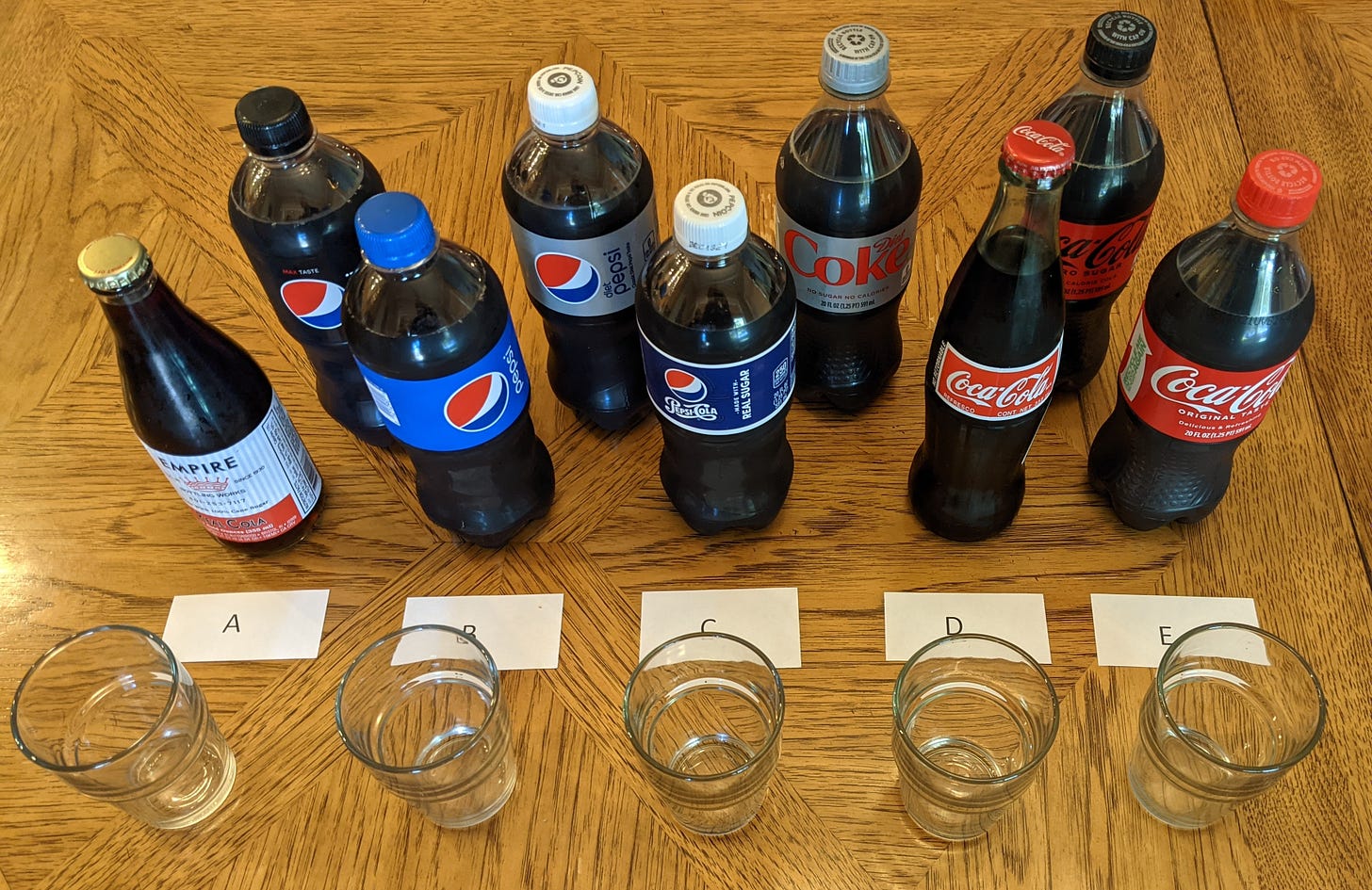

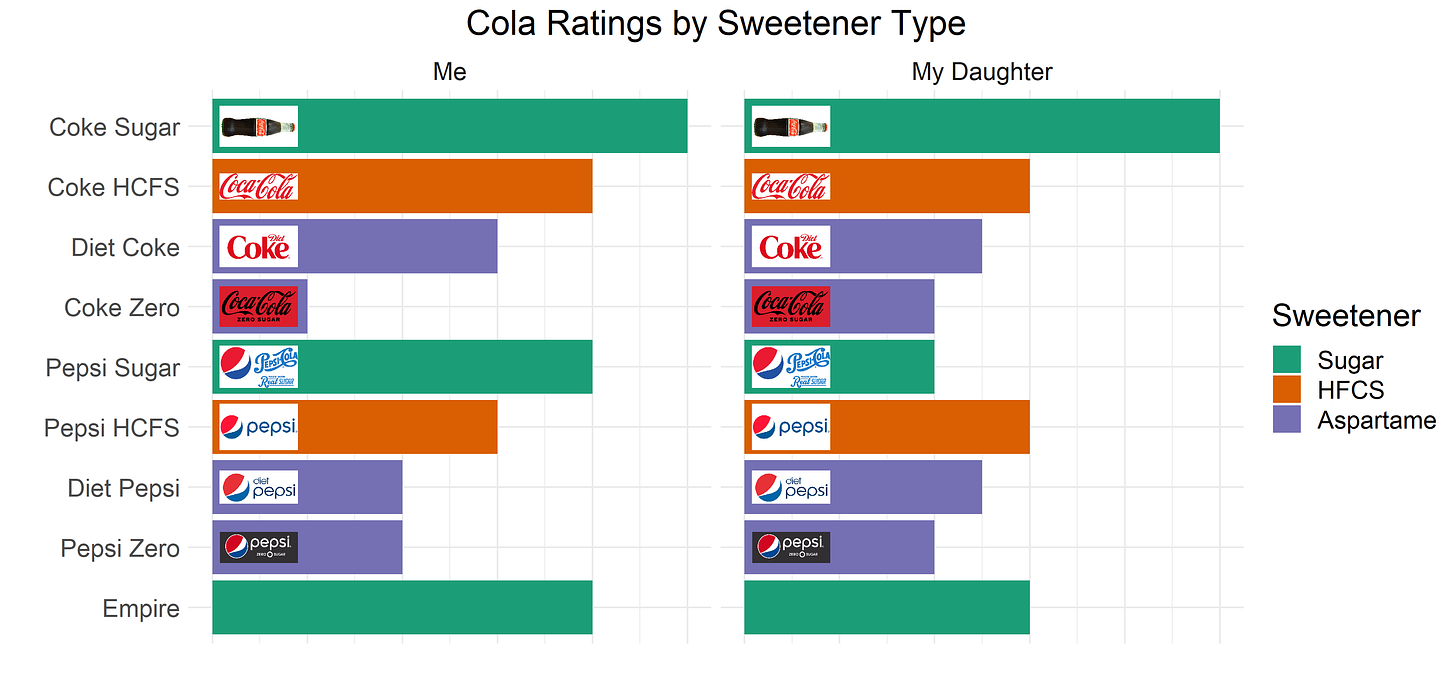

To answer this question, my daughter and I tasted four cola products from Coke and Pepsi. From each brand, we tasted one cola sweetened with sugar, one sweetened with HCFS, and two sweetened with aspartame. Both Coke and Pepsi have "diet" product and a "zero" product. It seems each developed their zero product in an attempt to improve their diet recipe. We also tasted a cola made by Empire and sweetened with sugar.

I bought one bottle of each product at the grocery store and stored them in the fridge for a few days. Coke made with sugar and the Empire cola came in glass bottles, and the others were in plastic bottles. Here is our protocol:

Person 1 pours some of each of the five caloric sweetened colas into glasses, and labels each glass with a letter from A to E so the taster doesn't know what they are tasting.

Person 2 tastes the five beverages and rates them on a 0 to 5 scale according to three three criteria: flavor, aftertaste, sweetness.

Person 1 directs Person 2 through a sequence of pairwise tastings, e.g., taste A and B and tell me which you like the best.

Switch roles and repeat 1-3.

Repeat 1-3 for the four artificially sweetened beverages.

Tasting the caloric sweetened drinks separately from the artificially sweetened made the number of simultaneous comparisons manageable. The taste of aspartame is so distinctive that we would never mistake a caloric sweetened drink for an artificially sweetened one. (Yes, I did verify this with additional blind tastings.) The results from our pairwise comparisons (step 3) were the same as implied by our quantitative ratings, so I won't show those results separately.

Our favorite was Coke sweetened with sugar, also known as Mexican Coke as it is typically imported from Mexico. I have always thought I liked it better. Apparently, I really do. My wife, whose palate is more refined than mine, observed that sugar seemed to mask some tangy flavors that HCFS did not. I also liked sugar better than HCFS in Pepsi, but my daughter disagreed.

We both liked Coke better than Pepsi.

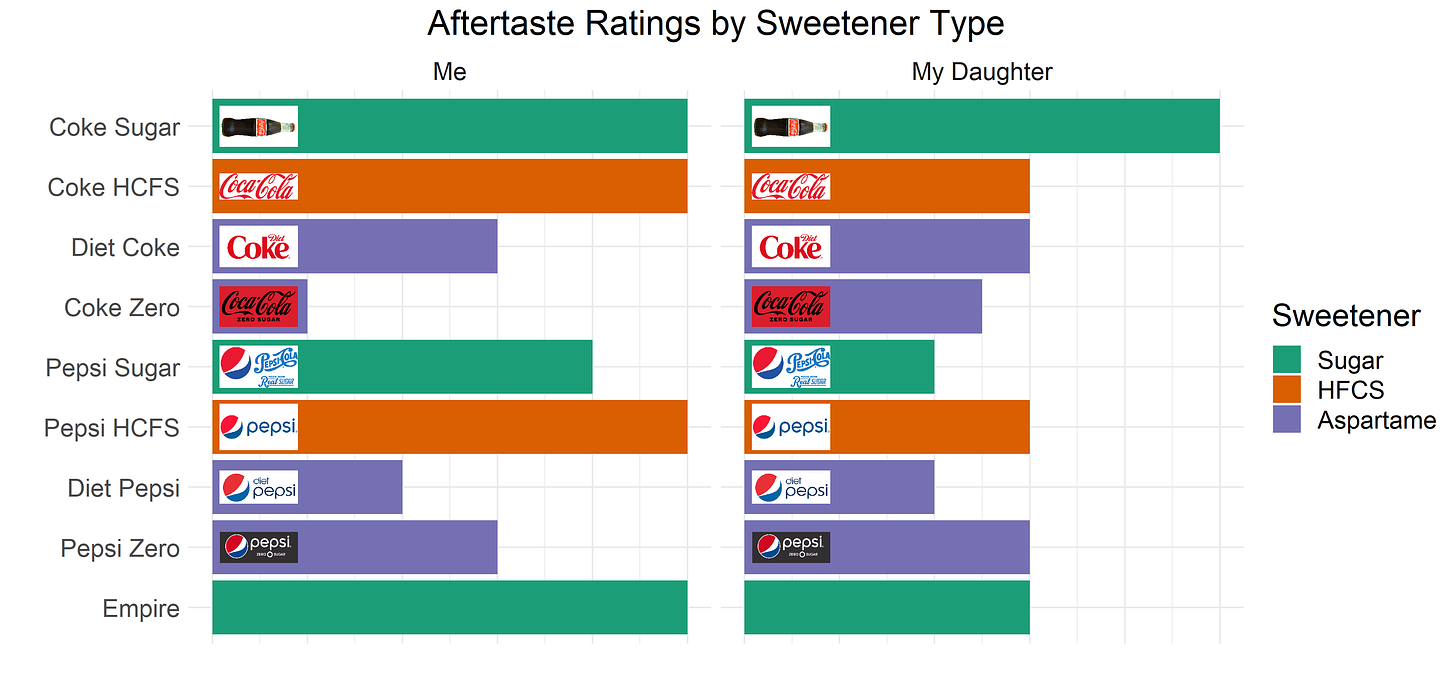

We both liked the caloric-sweetened drinks better than the diet products, and we liked the older diet-brand products better than the newer zero-brand products. Mostly, this was due to the unpleasant aspartame aftertaste, which I found most apparent in the brand new Coke Zero product.

All the calories in cola come from the sweetener, but our favorites were not necessarily the highest in calories. Empire Cola was slightly higher in calories than the others. There is little calorie difference between the Coke and Pepsi products.

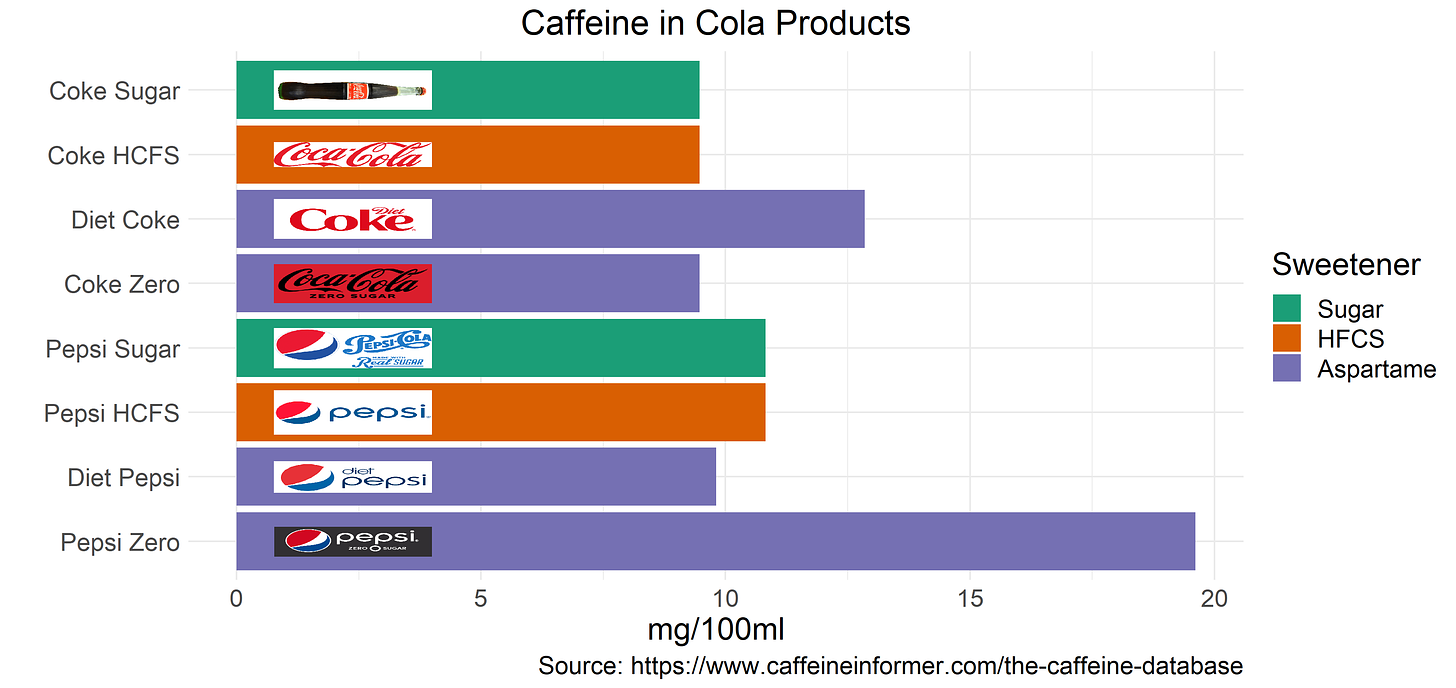

Some people drink cola for the caffeine. If that's you, you probably should go with Pepsi Zero. Or coffee, which tastes better than cola and has 3-5 times as much caffeine per 100ml.

In conclusion, Mexican coke wins the cola wars.

You can generate the figures in this article using this R code.

This article is the third in our sequence of taste-offs: