New Zealand Agriculture Proposes To Tax Itself, But How Much?

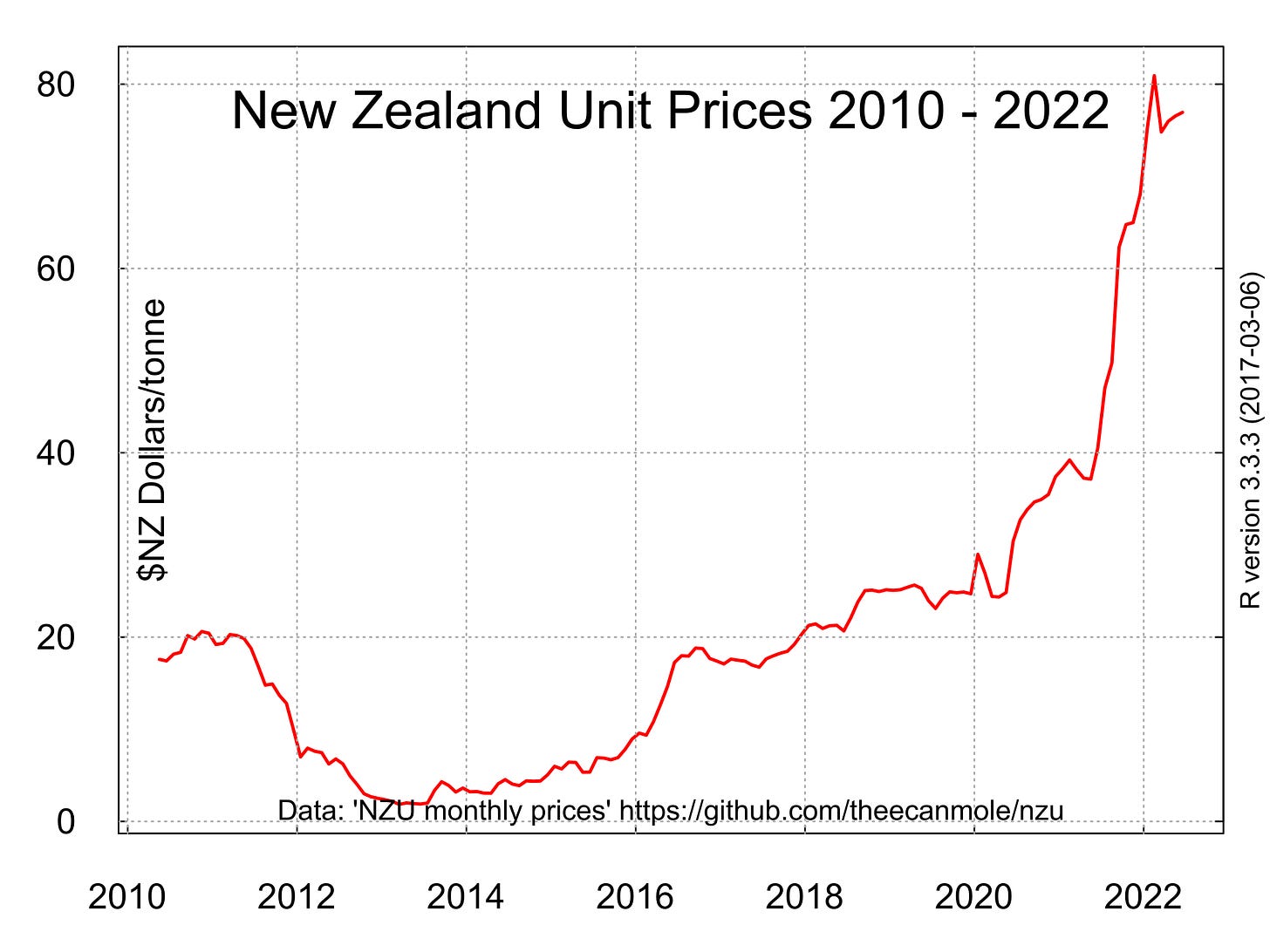

At the core of its climate policy, New Zealand has an emissions trading scheme (ETS) in which regulated firms must acquire an emissions credit for every tonne of greenhouse gas they emit. Agriculture is currently not required to participate in the ETS, but is slated to join in 2025.

Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture are not regulated anywhere in the world, as far as I know. There are programs that allow agricultural entities to get paid for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, such as in California's Low Carbon Fuel Standard, but none that tax emissions or require reductions.

When the ETS started in 2008, the plan was for agriculture to enter in 2015. We're seven years past that deadline. I would normally be skeptical that agriculture will meet the 2025 deadline, except a partnership between the government and the agricultural sector has been developing a viable proposal.

Last week, the partnership, known as He Waka Eke Noa, released their recommendations.

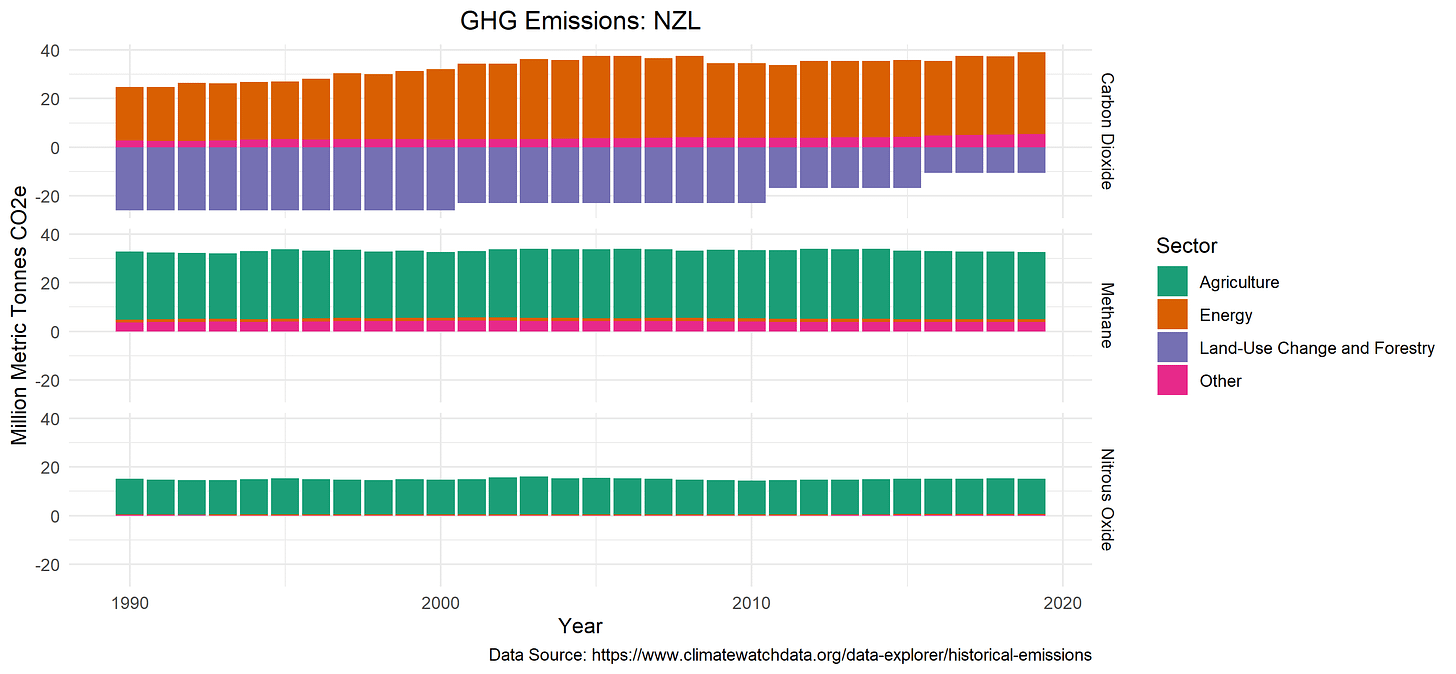

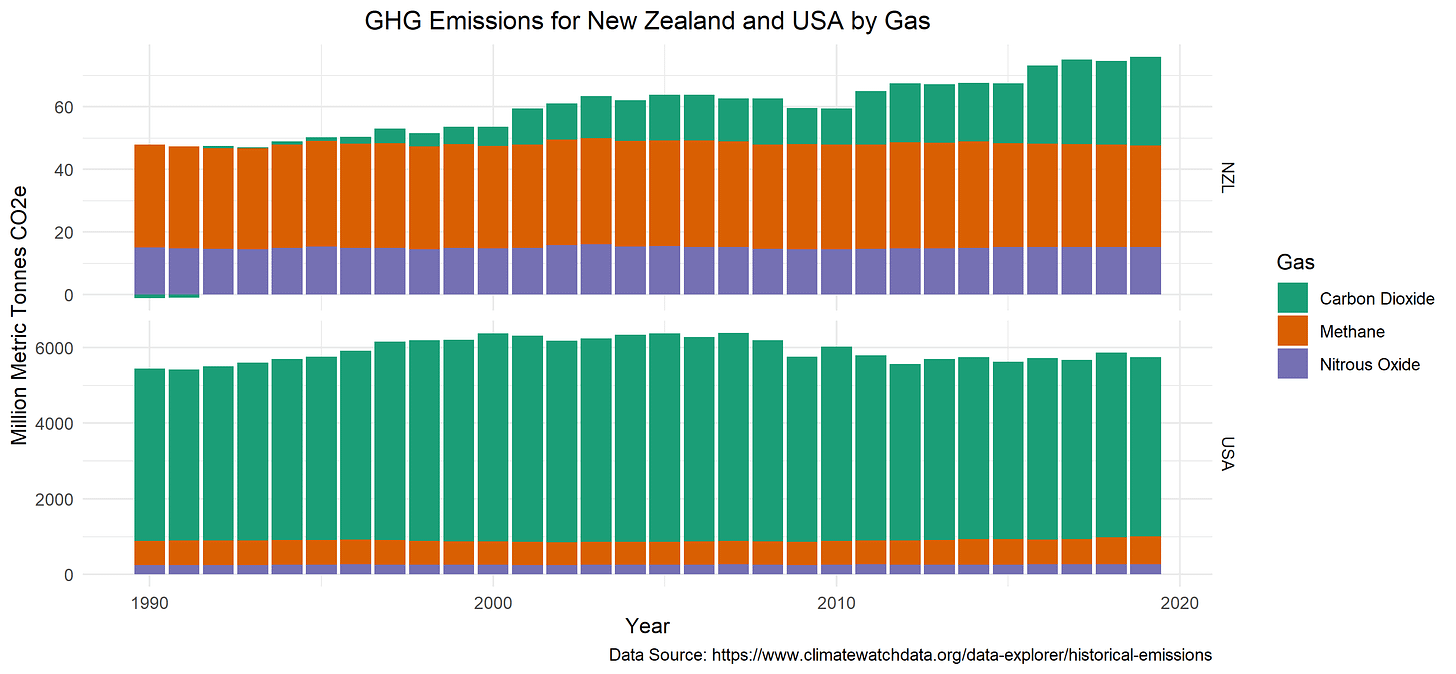

Before digging into the recommendations, here's some background. Greenhouse gases fall into three main categories: carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O). New Zealand's agricultural emissions are essentially all from either methane (mostly sheep and cattle burps and manure) or nitrous oxide (mostly from nitrogen fertilizer).

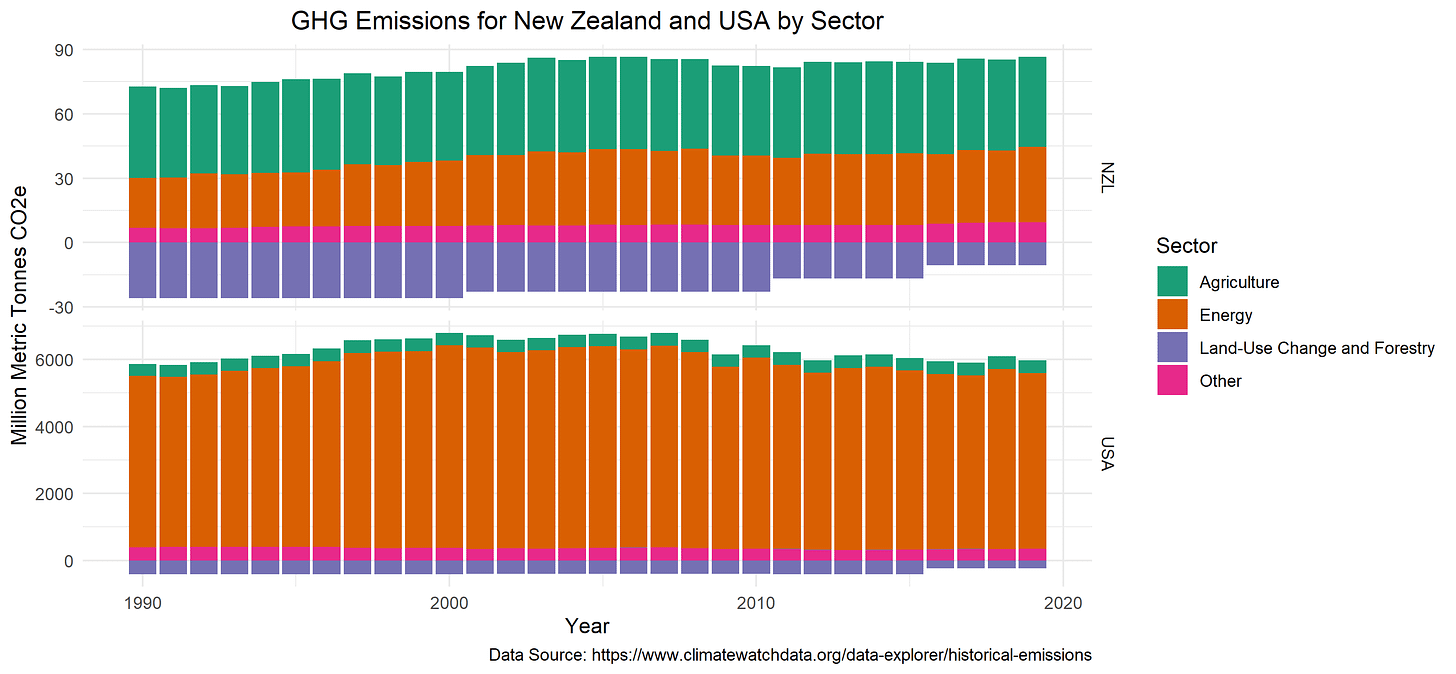

New Zealand's GHG emissions are dominated by agriculture. According to the models that estimate these things, the country emits as much methane and nitrous oxide from agriculture as CO2 it emits from energy for electricity, transportation, heat, and industry. In contrast, US emissions are dominated by energy provision.

New Zealand's CO2 emissions were estimated to be close to net zero in the early 1990s due to carbon sequestered from newly planted forests. The estimated amount of sequestration as declined in recent years as the estimated carbon removal benefits of the forests diminish. It is clear that New Zealand can do little to reduce its emissions without addressing methane and nitrous oxide from agriculture.

He Waka Eke Noa proposes a levy (tax) of $NZ110/t of methane in 2025 that rises to around $NZ170/t to $NZ350/t by 2030. They estimate that this levy would result in a 4% reduction in agricultural methane emissions. (To convert to US dollars, multiply by two thirds.)

One way to convert methane emissions to a CO2 equivalent is to multiply by 28. Converting to CO2 equivalent using this factor and converting to US dollars, the proposed levy is equivalent to a carbon dioxide tax of $US2.60/t in 2025, increasing to $US4 to $US8 by 2030.

For nitrous oxide, He Waka Eke Noa propose a levy of $NZ4.25 per tonne of CO2 equivalent, rising to $NZ13.80 in 2030 (i.e., $US2.80 rising to $US9.20). Both of these taxes are very low relative to the estimated social cost of carbon, which is typically at least $US50. They are also very low relative to the price of credits in the NZ ETS, which is currently over $NZ70 ($US47).

Methane affects the climate very differently than CO2 over time; it lasts about 12 years in the atmosphere, whereas CO2 lasts for centuries. This fact creates an argument for a lower tax on methane, but not that much lower. See this Ag Data News article for more on that topic.

To determine how much each farm owed, emissions of methane and nitrous oxide would be estimated using a model. Measuring these emissions is infeasible with current technology.

The He Waka Eke Noa proposal allows for farmers to reduce their levy in two ways. First, they can receive credit for sequestration of carbon in vegetation on their farm. They propose crediting sequestration at rates tied to the ETS. They project reimbursement at $NZ64/t in 2025, rising to $NZ104 in 2030. So farmers would receive 10 times the credit for sequestration as they would pay for emissions.

The report discusses the principle of additionality (i.e., paying farmers to do something they would do anyway doesn't reduce greenhouse gases in the atmosphere), but it recommends setting 2008 as the baseline year rather than 2025.

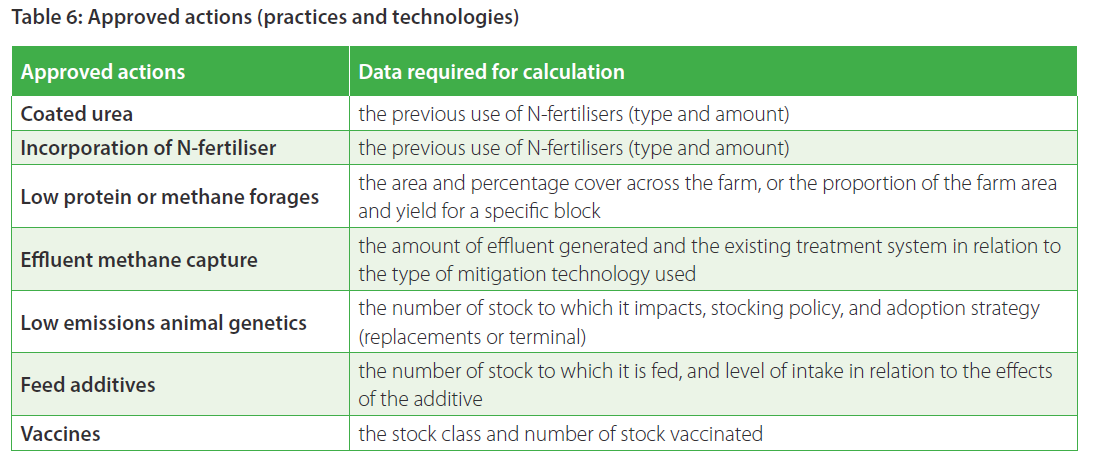

Second, farmers can receive a discount for actions that reduce emissions, including low-methane feed, low-methane genetics, and effluent methane capture. They rejected credits for soil carbon on the grounds that the science isn't there yet.

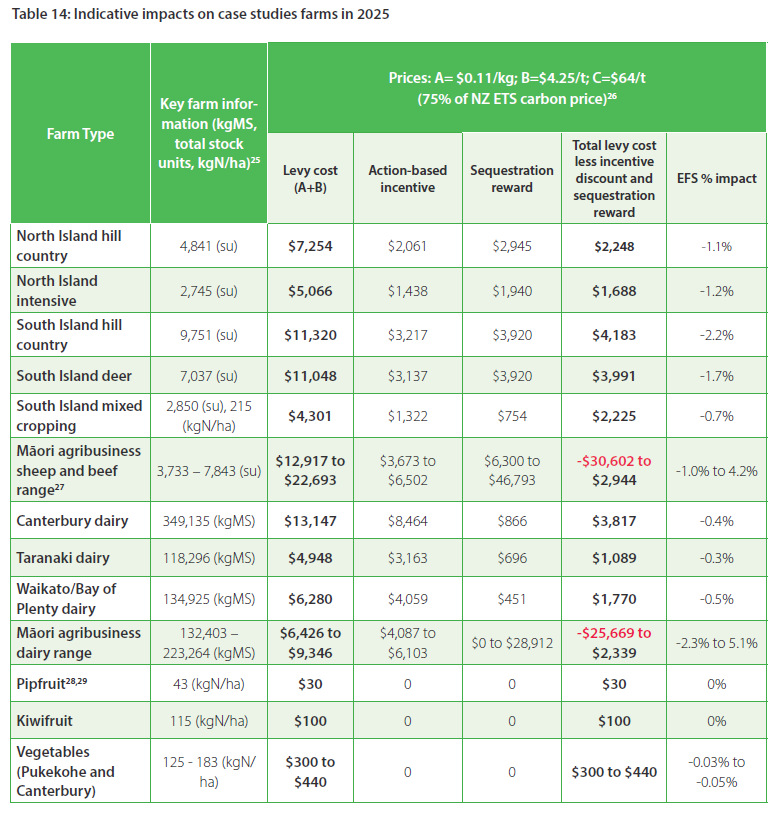

They modeled the likely levy amounts on several representative farms. For example, a South Island hill country farm on 1562 hectares with 9000 sheep and 700 cattle would owe a levy of $NZ11,320, which would be reduced to $NZ4,183 after credit for sequestration and emissions-reducing actions. That's less than 50c per animal on the farm. For more details on this and other sheep, beef and deer farms, click here.

A Canterbury dairy with 800 cows on 240 hectares producing 349,000 kg of milk solids would owe a levy of $NZ13,147, which would be reduced to $NZ3,817 after credit for sequestration and emissions-reducing actions. That's about $5 per cow. For more details on this and other dairy farms, click here.

So, the proposal is for a small levy that is much lower than the social cost of greenhouse gases. But, at least it's a levy, which is more than anyone else can say. And, as a small exporting country, it may be difficult for New Zealand farmers to pass the levy along to consumers.

He Waka Eke Noa is a Maori proverb that translates to "We are all in this canoe together". It means that everyone is coming together for a shared purpose. However, Google translates He Waka Eke Noa as "It's a Free Ride".

Let's hope this initiative reflects the true meaning of He Waka Eke Noa and not the Google translation.

Read the full He Waka Eke Noa report here. I made the emissions graphs using this R code.