This article was written by UC Davis students Diogenes Cruz and María de la Paz Fraile. It is the fourth of several excellent articles written by students in my ARE 231 class in Fall 2023 that I'll be posting here.

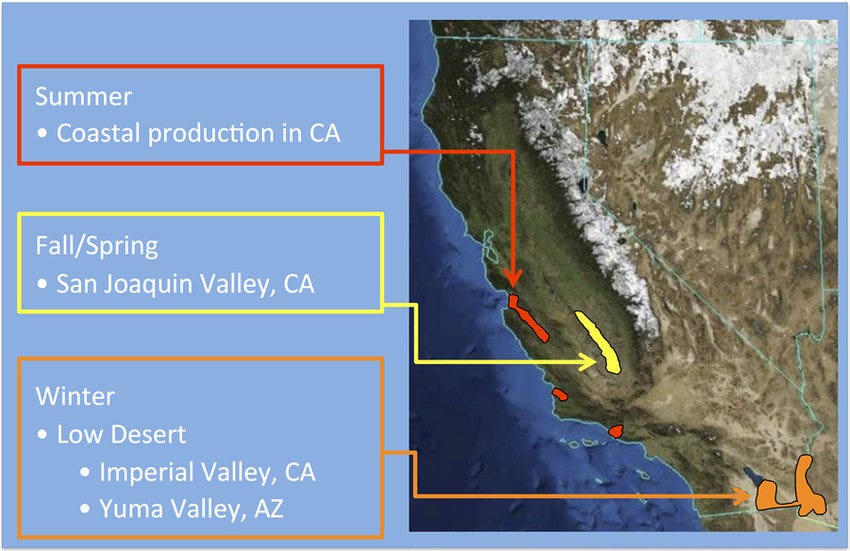

California and Arizona dominate production of lettuce in the United States. Production migrates from Yuma, Arizona and California’s Imperial Valley in the winter to Monterey County in the summer, with interludes in the San Joaquin Valley. On the front end, the lettuce supply chain operates with precision-like logistics, ensuring a year-round supply runs like clockwork (the Swiss kind). On the back end, this precision means dealing with a multitude of problems, including that of crop disease.

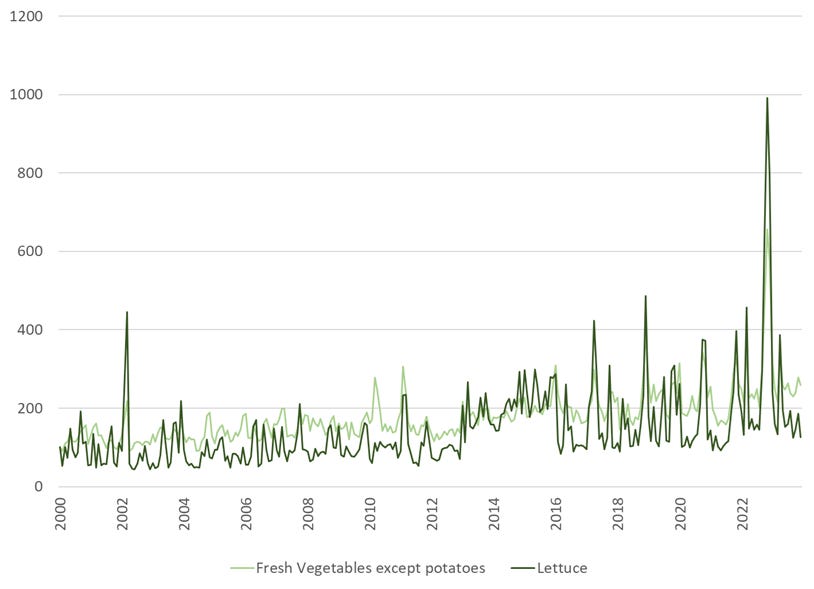

The concentration of production in the Southwest makes lettuce particularly vulnerable to weather fluctuations and diseases, including fungal, bacterial, and viral infections, whenever these hit the region. It almost seems to be a microbial conspiracy. Recent examples include the 2018 E. Coli outbreak and challenges with the impatiens necrotic spot virus (INSV), which hit Salinas Valley 2020 and 2022. In 2020, losses were estimated between $50 million and $100 million, according to Mary Zischke, former Executive Director of the California Leafy Greens Research Board.

INSV, as its name suggests, causes a disease that manifests as necrotic spots on the leaves, as well as yellowing and deformation of the leaves, and may even result in the death of the crop. Transmission of the virus usually occurs through the thrips insect, and until recently disease management was limited to avoiding sources of the disease.

USDA reports that between 1998 and 2019, 36 E. Coli outbreaks can be linked back to romaine lettuce harvested in California, mostly during the fall and winter seasons. A greater, more recent impact is 2022’s INSV, which caused lettuce prices to increase almost six-fold to an all-time high in October of that year.

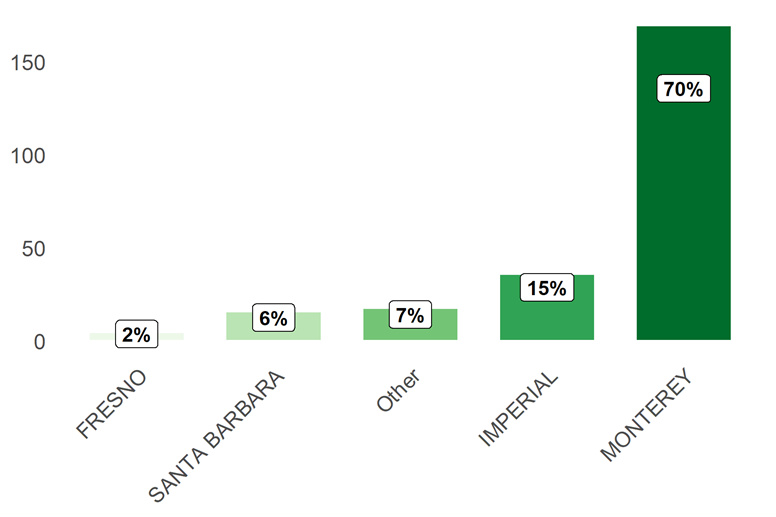

California's sun-drenched landscapes and agricultural expertise provide the state with a crucial advantage in cultivating lettuce year-round. California’s rotating lettuce production unfolds from the fertile Salinas Valley during summer, to the desertic Imperial Valley where production is concentrated during the winter season. During the summer, Monterey County accounts for most of California’s acreage dedicated to Lettuce alongside Santa Barbara; together they account for 76% of acreage, according to USDA’s Census of Agriculture. During Winter, production shifts south to Imperial County. During Spring and Fall, a lesser, but still noteworthy, share of the production takes place in the San Joaquin Valley.

Most of the lettuce acreage outside California is in Arizona, particularly concentrated in Yuma County. Yuma County is adjacent to California's Imperial County, and both regions share access to Colorado River water. This geographical proximity and shared access to water resources contribute to the significant lettuce production in the area.

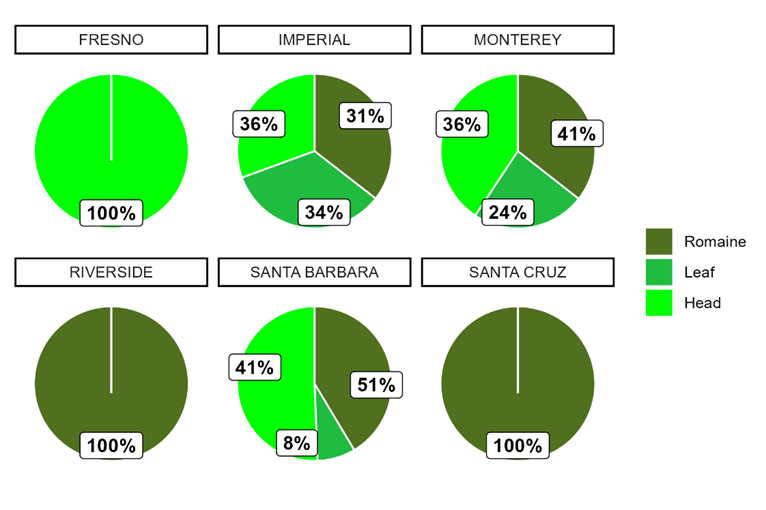

Seasons not only determine when lettuce is grown but also influence the specific types of lettuce cultivated in each county. In the three major production regions—Imperial/Yuma, Monterey, and Santa Barbara—acreage is predominantly diversified, encompassing various lettuce types.

However, lettuce production in smaller lettuce counties like Fresno, Riverside, and Santa Cruz, which specialize in one specific variety, could be more exposed to risks from diseases. Diversification becomes more important when considering that recent outbreaks have impacted mostly Romaine lettuce production.

Though it may appear that Fresno, Riverside and Santa Cruz are more exposed to disease, lettuce production in these counties is smaller compared to other crops, like grapes and dates in Riverside, or berries in Santa Cruz. For Monterey, however, lettuce production value, regardless of variety, exceeds any other cultivated crop in the area. Monterey was hit hardest by the INSV outbreak.

Take the 2019 annual crop report for Monterey County as an example. It revealed a substantial surge in romaine and head lettuce revenues, making lettuce the highest-grossing crop that year at $1.87 billion. However, the celebratory mood quickly soured as the coronavirus caused widespread worldwide. Reduced demand from restaurants led to losses for farmers in the Salinas Valley, with some sites reporting the large reductions in the land allocated to lettuce farming, as well as some farmers letting the crop to die. In 2020, lettuce production in Monterey showed a decrease of over 6,000 acres, and value of production dropped 16%.

In the face of these challenges, the government and industry have pushed efforts to build resilience. In 2022, USDA called for a research project for lettuce breeding that result in improved resistance to INSV, Pythium and other diseases. In 2023, Dutch company Rijk Zwaan launched two INSV resistant romaine lettuce varieties in the US market, with pellets seed available early in the year. The company claims it intends to launch other resistant varieties for different types of lettuce in the future.

Consumers and producers stand to benefit from a more dependable and diverse lettuce market, demonstrating the economic importance of investing in biotechnology and breeding practices that can overcome both agricultural and market challenges. Ultimately, success will depend on technological progress, and farmers willingness to adopt these newer technologies.

Thanks for continuing to share your students’ great work.