In Arguments About Soccer and Ethanol Ask What Would Have Happened?

Frenchman Karim Benzema was awarded the Ballon d’Or as the world best soccer player in 2022. The award capped a roller coaster career in which he first played for France as a 19 year old. He was left out of the team that won the 2018 World Cup before returning in 2021 and immediately forming a potent scoring partnership with Kylian Mbappé.

French fans became increasingly optimistic that the two stars would lead them to World Cup victory in 2022, becoming the first nation to repeat as champions since Brazil in 1958 and 1962.

Unfortunately, Benzema tore a thigh muscle just before the World Cup and was unable to play for most of the tournament. It initially appeared that France didn’t need him as they cruised through the tournament. They played Argentina for the championship last Sunday. Benzema had recovered from his injury by then, but the manager chose not to play him.

In a compelling contest that some called the best game ever, France lost. Argentina was crowned the World Cup winner.

What would have happened if Benzema had not gotten injured? Would France have won?

To answer these questions, you need to articulate the counterfactual. You need to describe what would have happened if Benzema had been playing so you can compare it to what did happen.

The same is true when evaluating government policies. The Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) essentially mandates that an area the size of Kentucky be used to grow corn to make ethanol for transportation fuel in the United States. To make an argument about how this policy has affected greenhouse gas emissions, you need to articulate what would have happened absent the policy.

Since February when my co-authors and I published our paper estimating environmental outcomes of the RFS, I have read multiple critiques that fail to grapple with the fundamental question: what would have happened absent the policy?

Some critics say the price of corn in recent years was similar to its value prior to the RFS, so the RFS didn't cause corn prices to go up. Some say that crop yields have increased by enough to cover the RFS mandate, so the policy didn't require more cropland. These arguments describe what happened but not what would have happened in the absence of the RFS.

This week, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences published a response we wrote to the latest such critique of our paper.

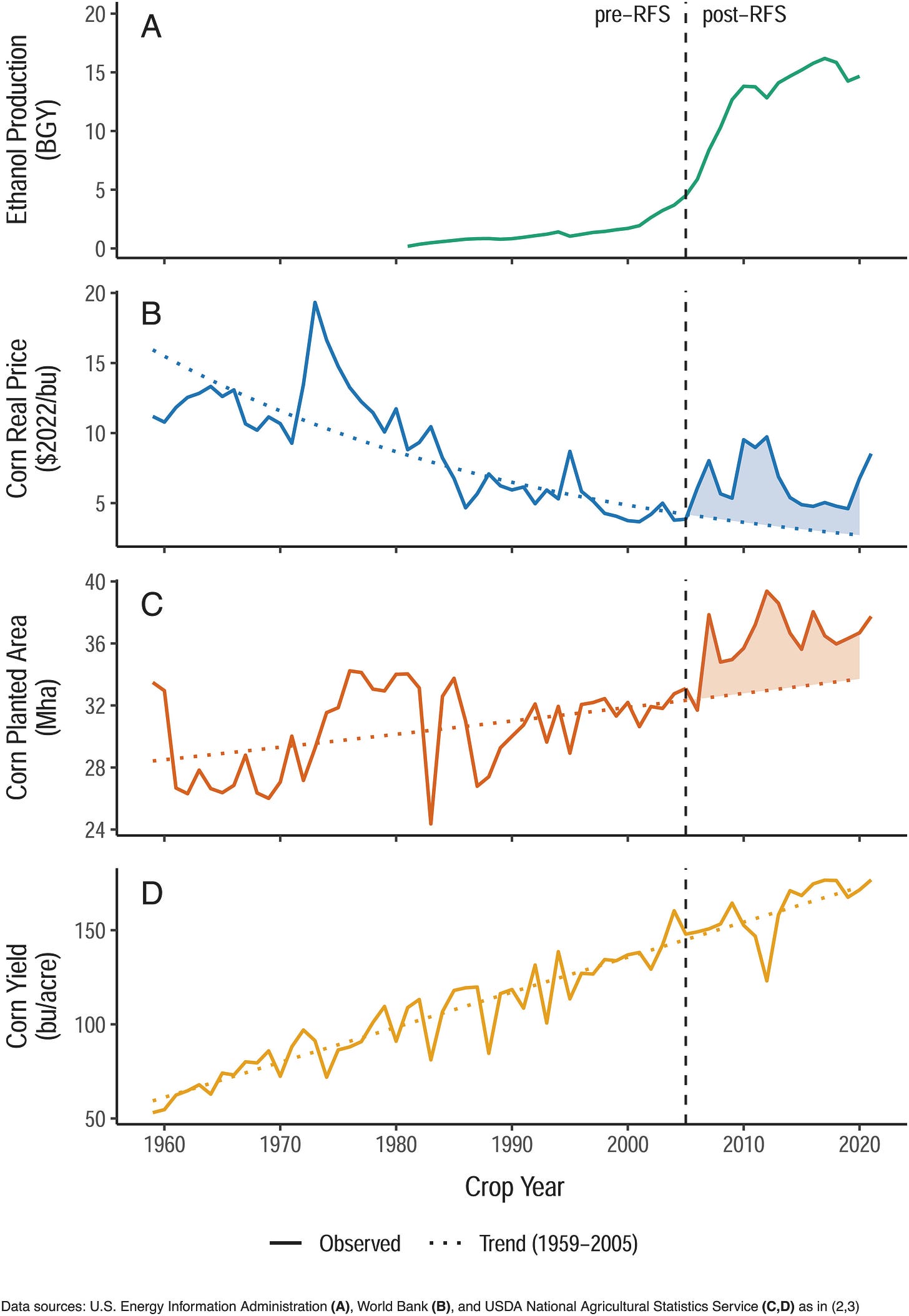

It includes the figure below, which illustrates our findings that (i) corn prices were higher after the RFS than they would have been, (ii) corn planted area was higher after the RFS than it would have been, and (iii) yield was similar after the RFS to what it would have been.

Our model is richer than a comparison of actual data to their trendlines, but such comparisons illustrate the main findings. Agricultural productivity has increased over time, generating an upward trend in yields. This increase in supply has caused a downward trend in prices. At the onset of the RFS, corn prices jumped above their trend, which caused farmers to plant more acres than they would have absent the price jump.

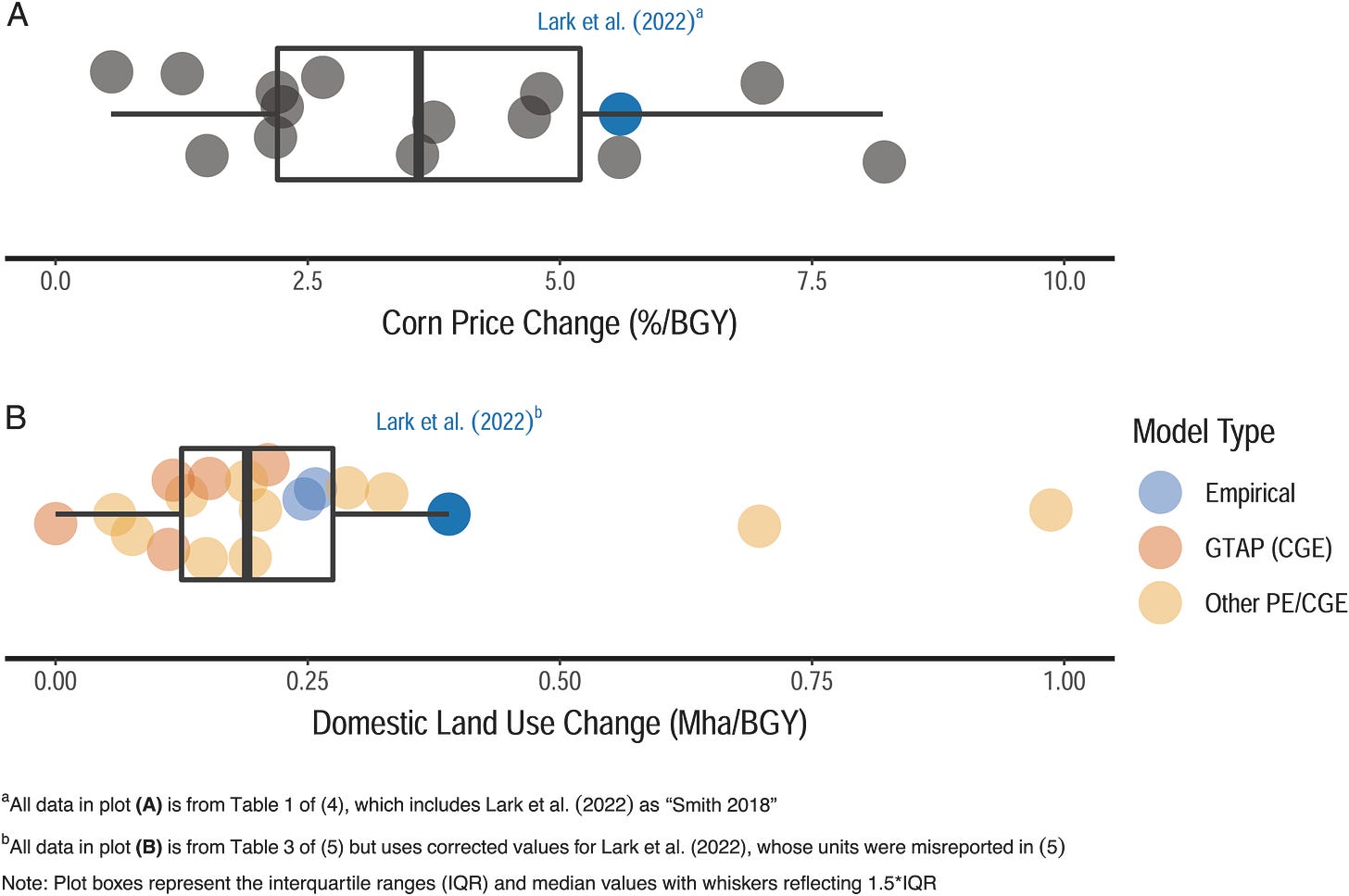

In our reply, we also address a critique that our findings are less credible because they differ from those from prior studies. We believe departing from entrenched modeling frameworks was necessary to advance knowledge in this domain. Regardless, our results for both corn prices and LUC responses actually fall within the ranges of prior studies. Our larger carbon intensity estimates for expanded corn ethanol instead arise largely from variation in LUC emissions per unit area and likely stem in part from systematic underestimation bias in some previous works.

So, whether it's Benzema in the World Cup or ethanol in our fuel tanks, claims about how much something matters require you to articulate what would have happened otherwise.

Postscript: Yes, I call it soccer. New Zealand, where I grew up, and the US, where I now live, are two of the few countries in the world where a different version of “football” is much more popular than soccer. William Webb Ellis created what is now New Zealand’s most popular sport when he picked up the ball and ran with it during a soccer game. My grandparents called the resulting sport football, but it’s now mostly known as rugby. The sport we now know as American football evolved from rugby football and association football (soccer).