I Hear the RD Train a Comin'

This article is co-authored with ARE PhD candidate Dan Mazzone.

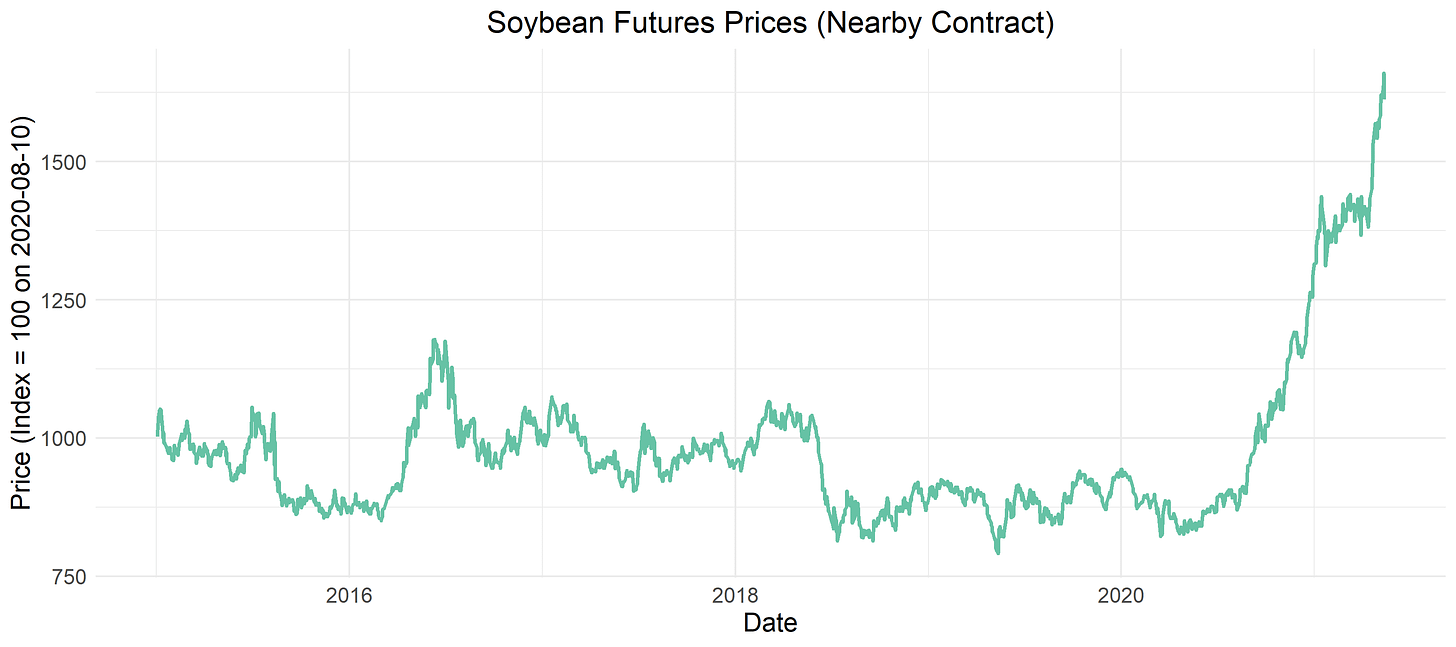

Prices for the major US crops are booming. Soybean prices have almost doubled since August 2020 and are now around the values from the 2011-14 boom. The proximate cause of the soybean price runup is increased demand from China, which raises costs to other soybean users. It also obscures the renewable diesel (RD) freight train that is about to hit the soybean market.

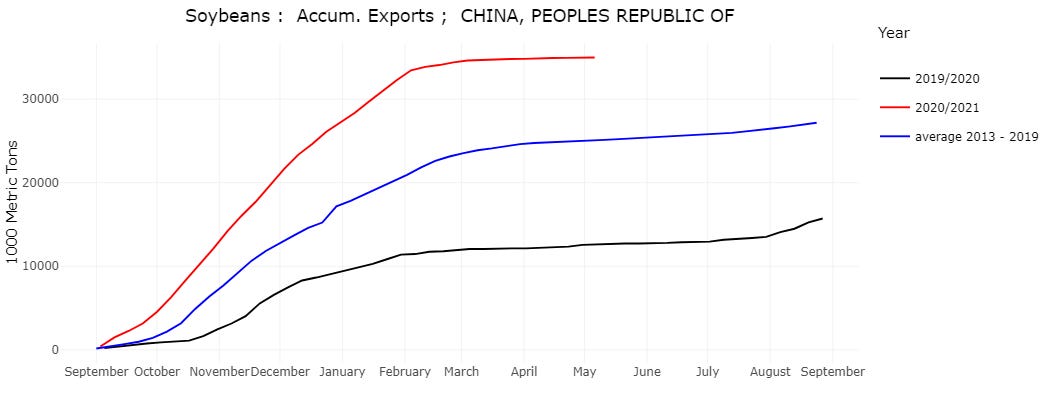

US soybean exports to China reached record levels in late 2020 and early 2021. They have rebounded strongly from the trade-war induced lows of 2018-20, and are the main reason that agriculture is the only covered sector to be close to meeting the targets set by the US-China phase one trade agreement.

About half of US soybeans are exported. The remainder are crushed into meal and oil; most soybean meal is fed to animals, and most soybean oil enters the food system. By weight, just over 80% of the soybean becomes meal. In the past decade, an increasing percentage of soybean oil has been used to make biodiesel, reaching 34% this year.

Under the Federal Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS), about 4% of diesel consumed in the US is produced from biomass. The RFS requires at least 2.43 billion gallons of biomass-based diesel be used for transportation in both 2020 and 2021. About 1.3 billion of these gallons will be made from soybean oil in each year; the remainder will come mostly from used cooking oil and animal fat.

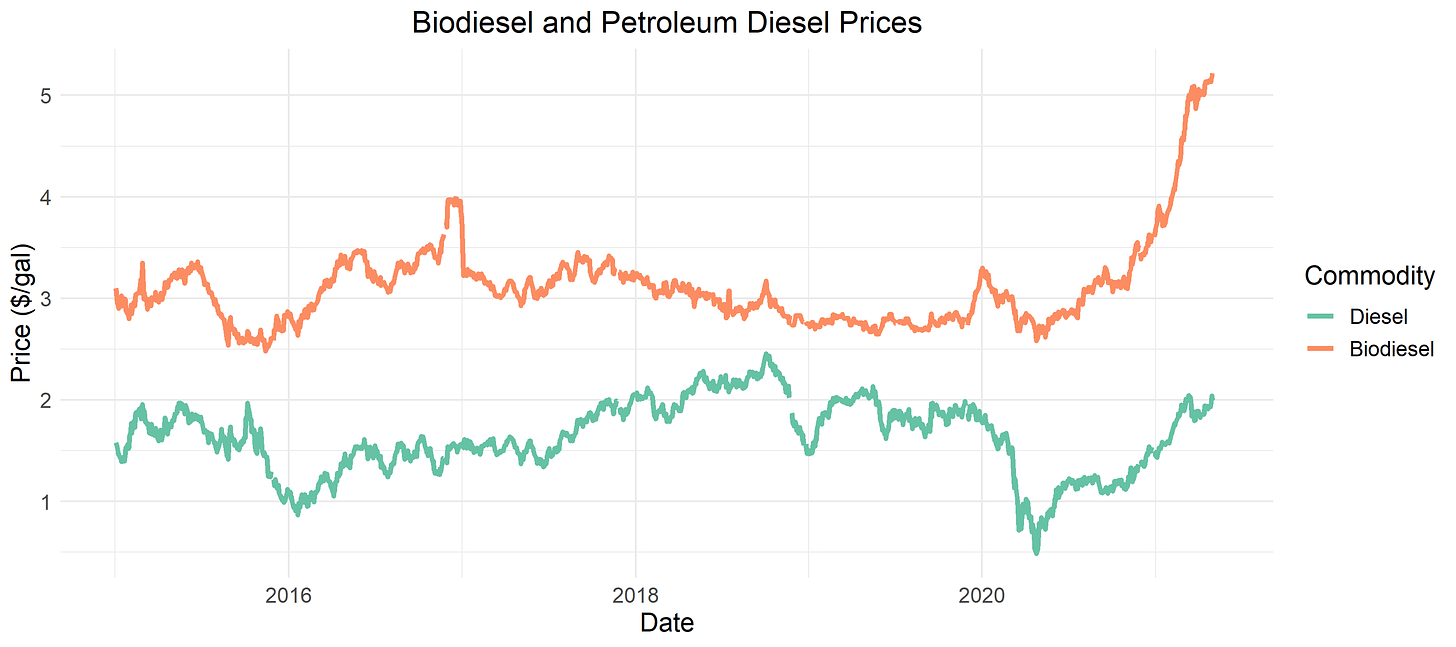

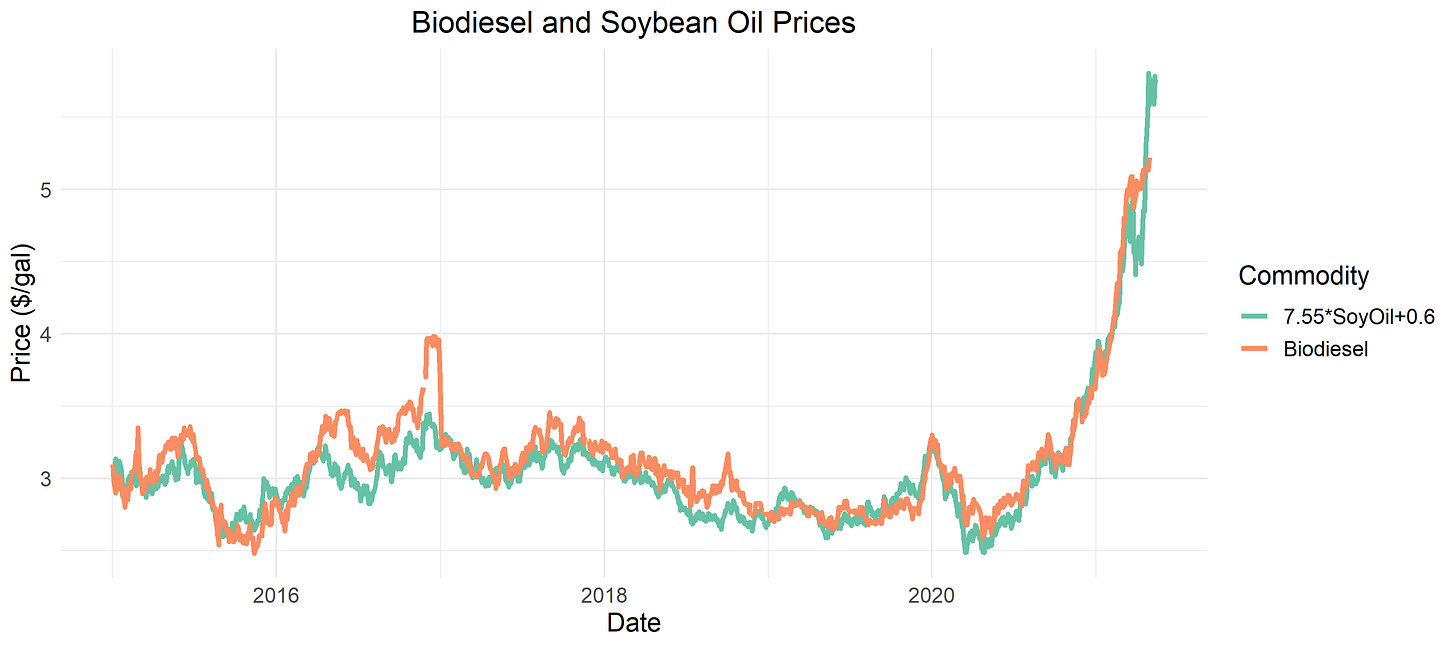

The increasing price of soybeans has raised the price of soybean oil, which in turn has raised the price of biodiesel. About 7.55 pounds of soybean oil are required to make a gallon of biodiesel. The per-gallon price of biodiesel equals 7.55 times the price of soybean oil plus $0.60. The $0.60 incorporates other costs and profit margin for biodiesel producers.

Biodiesel is substantially more expensive than petroleum diesel. Without government policies to compel its use, no biodiesel from soybean oil would enter the fuel supply. The main justification for requiring biodiesel is that it emits 60-70% less carbon per gallon than petroleum diesel.

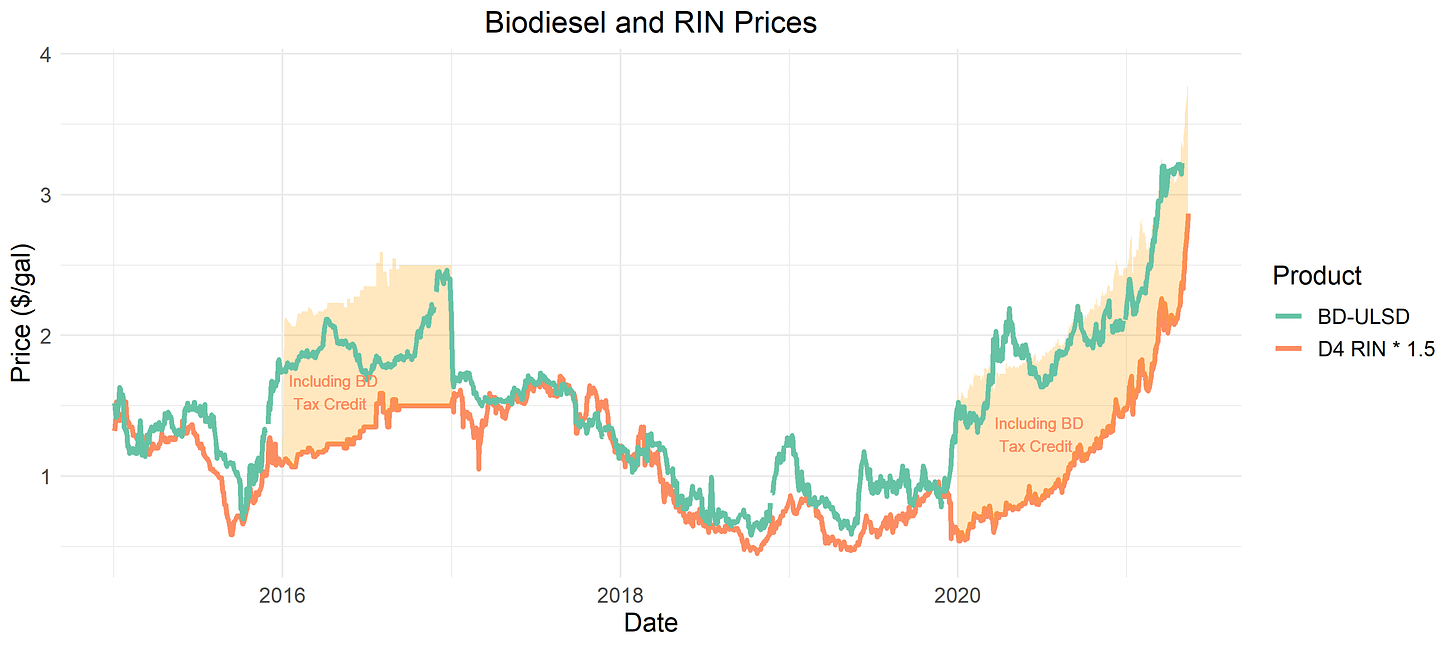

To compel fuel suppliers to blend biodiesel into their fuel to reach the RFS mandate, EPA uses a system of tradeable credits known as RINs. Fuel suppliers that sell biodiesel generate 1.5 RINs for every gallon. They sell these RINs to oil refiners, who must acquire RINs to demonstrate that the mandated amount of biodiesel has entered the fuel system.

Fuel suppliers will sell biodiesel if the RIN value is high enough to compensate them for the higher cost of biodiesel. In some years, suppliers also received a $1 per gallon tax credit for blending biodiesel. In those years, fuel suppliers will sell biodiesel if the RIN value plus the tax credit is high enough to compensate them for the higher cost of biodiesel. The RIN price has risen in the past 10 months to cover the gap created by rising soybean prices.

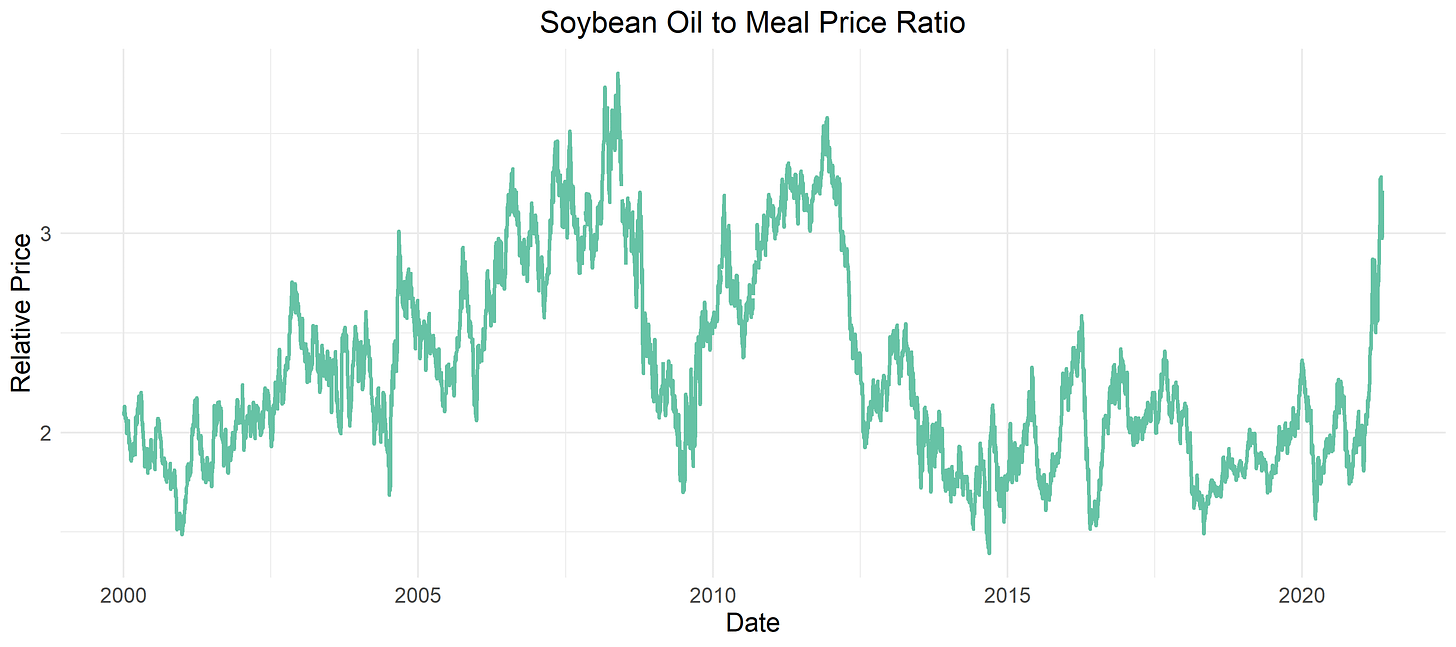

But that isn’t the end of the story. There is more going on in the soybean market than an increase in export demand. The price of soybean oil has risen much more than meal in the latest runup. Since August 2020, soybean meal has risen 50%, whereas oil has risen 120%. Oil is typically worth twice as much as meal, but that ratio now exceeds three (h/t Sebastien Poulliot).

The relative price of soybean oil to meal was also high in 2007/08 and 2010/11 but has fluctuated around two since 2012. In a 2017 farmdocdaily article, Scott Irwin argued that biodiesel demand did not drive the relative value of oil in the 2007-17 period. This time may be different due to the new kid on the block, renewable diesel (RD).

RD is a biomass-based diesel product like biodiesel. However, RD is a drop-in fuel, meaning it can be seamlessly blended with petroleum diesel, and refineries can use existing infrastructure to produce it. Several major oil companies such as Exxon, Valero have announced plans to build out significant RD capacity, most of which is expected to begin operation in the next 3 years.

RD production capacity is expected to increase nearly 5-fold to 2.65 billion gallons by 2024. That’s enough RD to cover the entire 2021 RFS mandate for biomass-based diesel. It is two thirds of California diesel consumption, so it would go a long way to reaching the state's low carbon fuel standard goals. Producing this fuel will require an additional 17 billion pounds of feedstock. With used cooking oils and animal fats being “nearly tapped out”, much of the new RD production is likely to come from soybean oil. The divergence of soybean and soybean meal prices foretells an increase in relative demand for soybean oil.

This paragraph was updated to clarify the effect of expanding RD on biodiesel production. This year, USDA projects that 9.5 billion pounds of soybean oil will be used to make biofuel, almost all of which will go to biodiesel rather than renewable diesel. Total domestic supply is 27.7 billion pounds, so using an additional 17 billion pounds for RD would leave little for food, feed and industrial uses (14.1 billion this year), exports (2.3 billion this year), or biodiesel. Even if biodiesel production goes to zero, accommodating RD will require a substantial increase in soybean production or a substantial decline in consumption by other users.

In addition to RD, biodiesel has another competitor for oil and fat feedstocks – sustainable aviation fuel, which is similar to RD, but for airplanes. As sustainable aviation fuel policies get implemented over the next several years, air travel will further increase demand for soybean oil.

Exports to China are driving the soybean market at the moment, but the RD train is a comin'.

We generated the graphs in this article using this R code. (Because the OPIS and Bloomberg data we use here are not publicly available, the code will not be able to replicate figures that use those data.)