Governments Like to Support Farmers

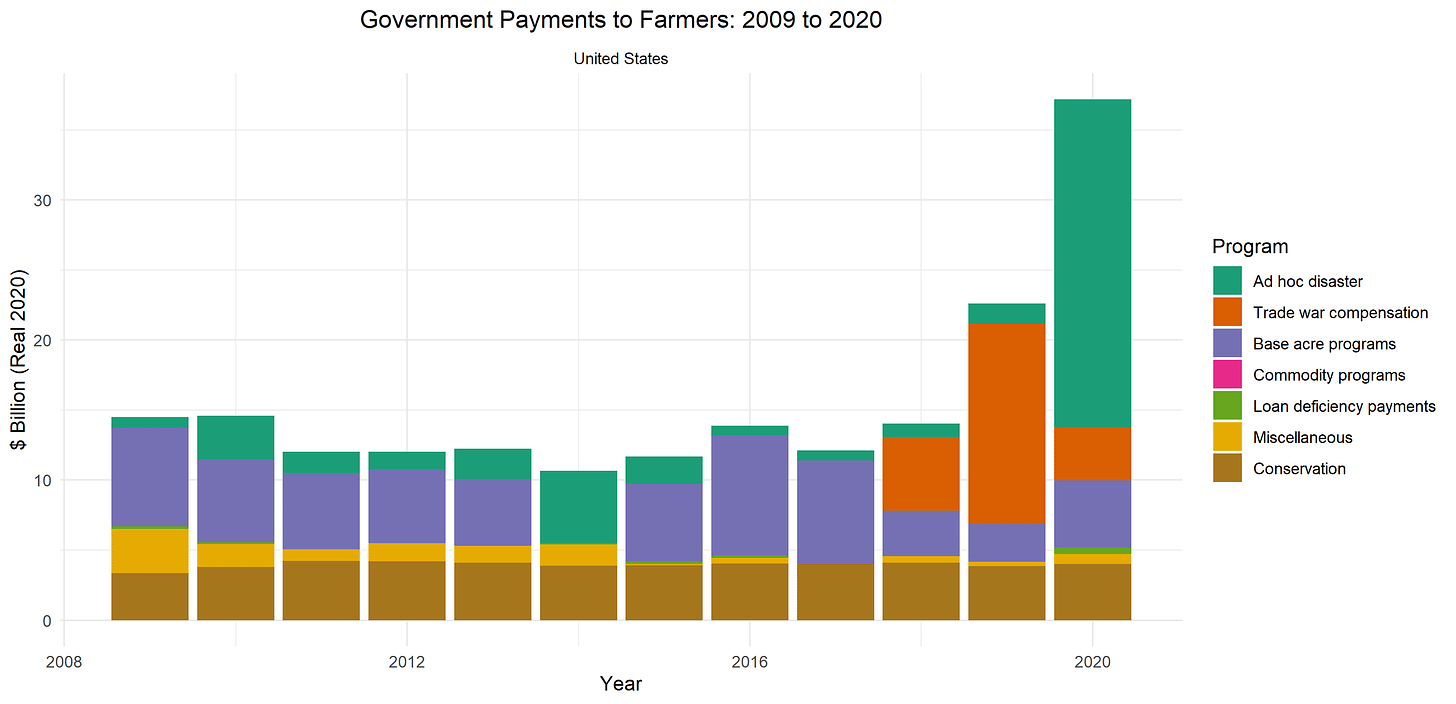

In 2020, the United States Government is expected to send $37.2 billion in aid to farmers, which exceeds inflation-adjusted payments in any previous year and is almost triple the average from 2009-2018. The 2020 payments are significantly higher than the 2019 payments, which were higher than in any year since 2005.

Much of the 2020 aid has been distributed through the Coronavirus Food Assistance Programs (CFAP1 and CFAP2), which USDA classifies as ad hoc disaster assistance. Most of the 2019 aid was to compensate farmers for losses due to the trade war with China, known as the Market Facilitation Programs (MFP1 and MFP2). These programs exist outside the farm support programs that Congress legislates periodically through the farm bill.

The trade war compensation (MFP1 and MFP2) focused on major crops such as corn, soybeans, and cotton. Research by UC Davis alumni Joe Janzen and Nathan Hendricks shows the payments significantly exceeded trade war losses on average.

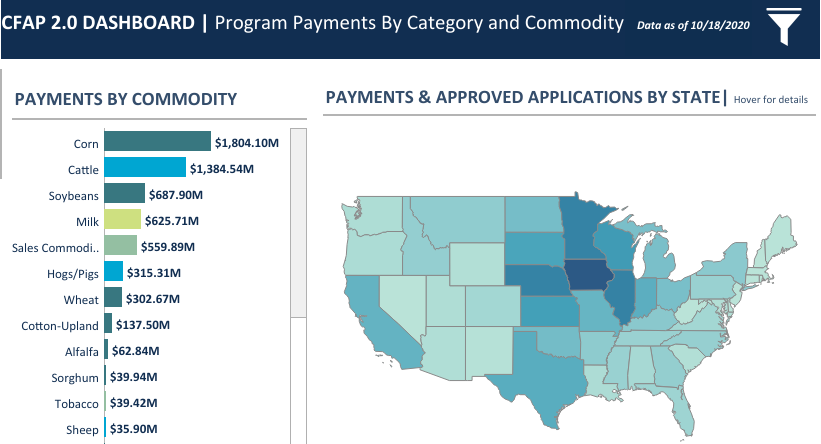

USDA's farmers.gov website contains detailed information on CFAP1 and CFAP2, including data dashboards that I used to obtain the two images below. These programs have delivered money mostly for corn, soybeans, and cattle (including dairy), which means that cornbelt farmers have received the most support. The payment formula was based on the amount that prices declined between January and April or July. For further analysis of these programs, see the farmdocdaily articles here for CFAP1 and here for CFAP2.

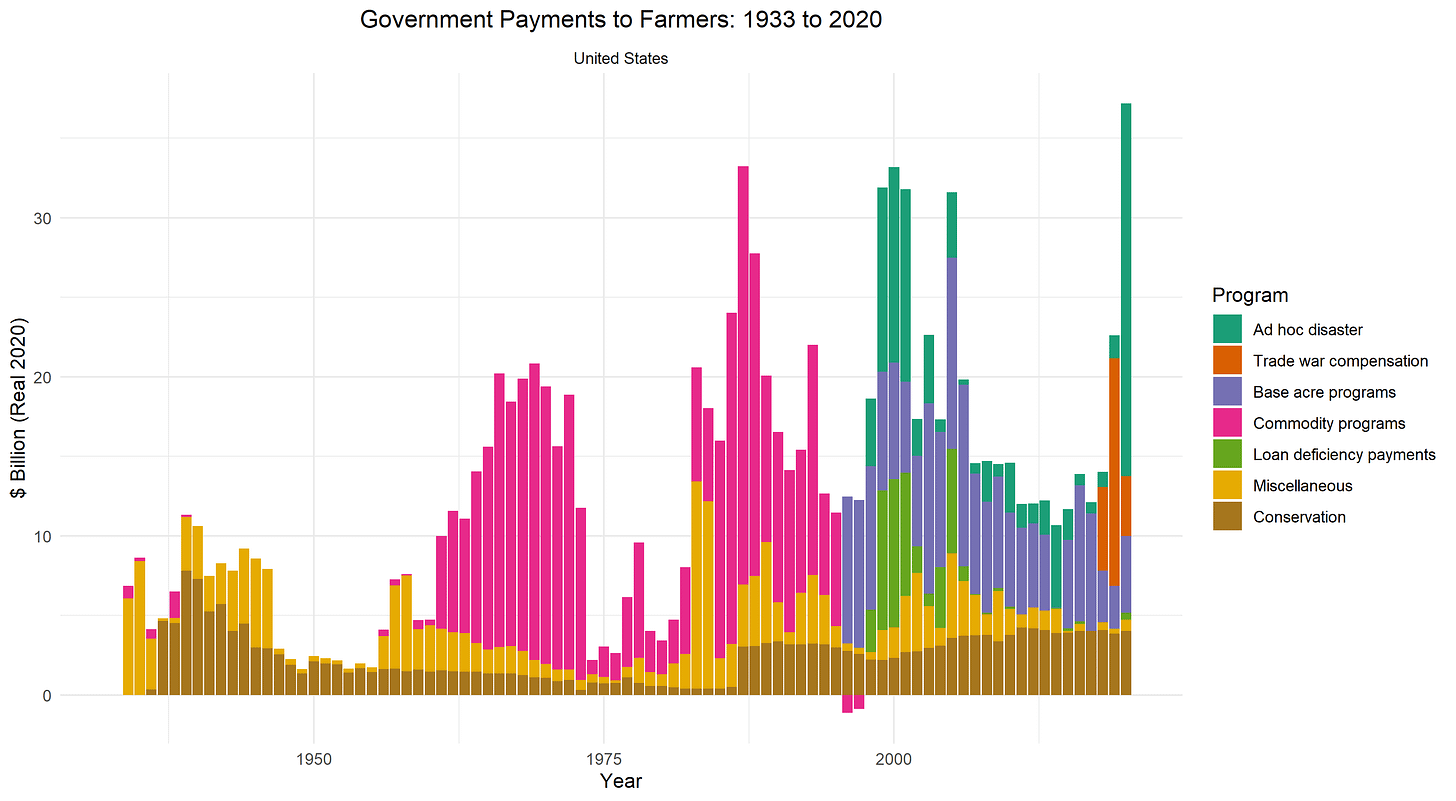

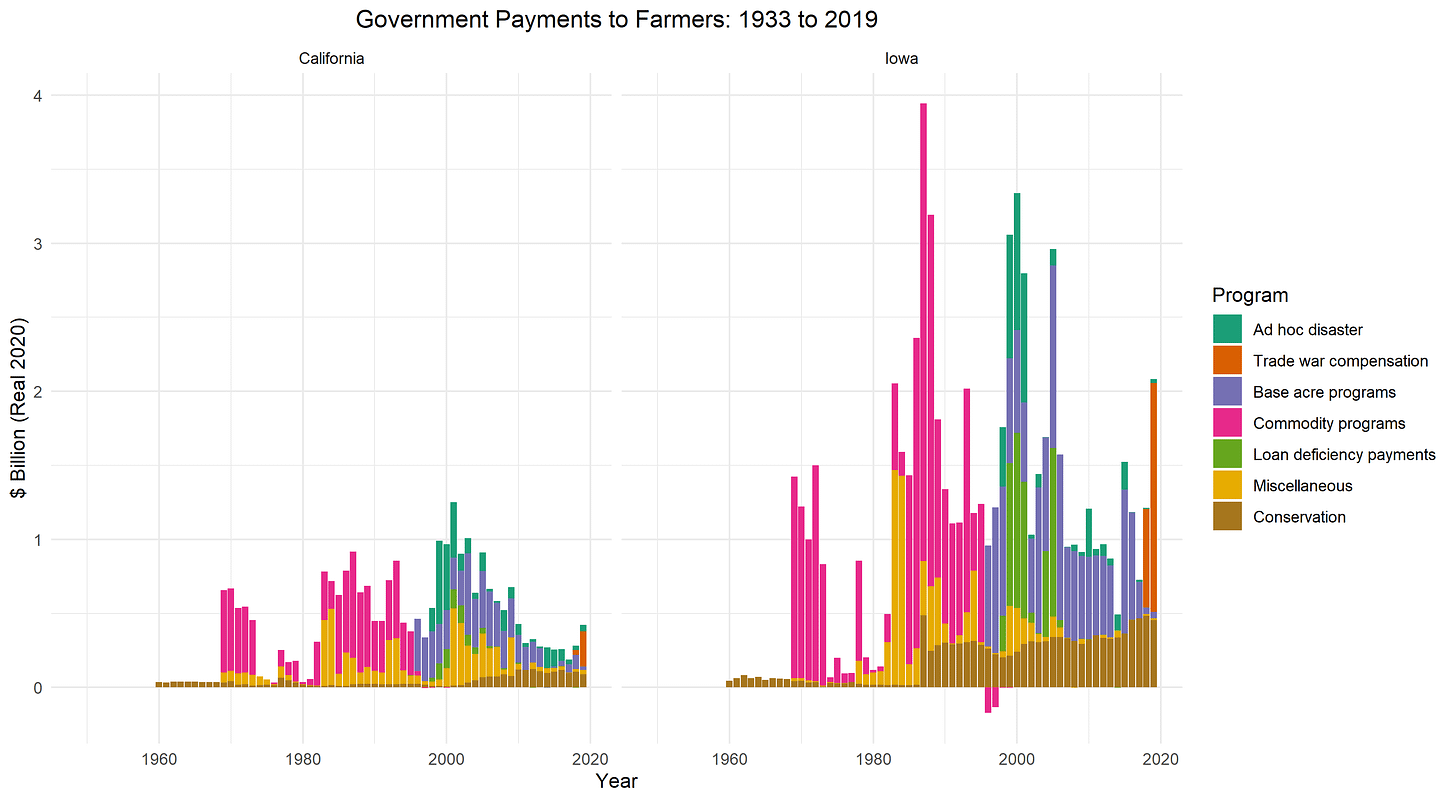

Substantial government payments to US farmers have persisted since the 1960s, apart from a period in the mid to late 1970s when high crop revenues reduced the demand for aid. Until 1996, most payments were subsidies for growing major crops such as corn, wheat, cotton, and rice (commodity programs).

Beginning with the 1996 Freedom to Farm Act, payments were decoupled from current production and instead tied to historical production (base acre programs). This change allowed farmers to make production decisions independently of the government, but it did not lead to a long-term decline in subsidies.

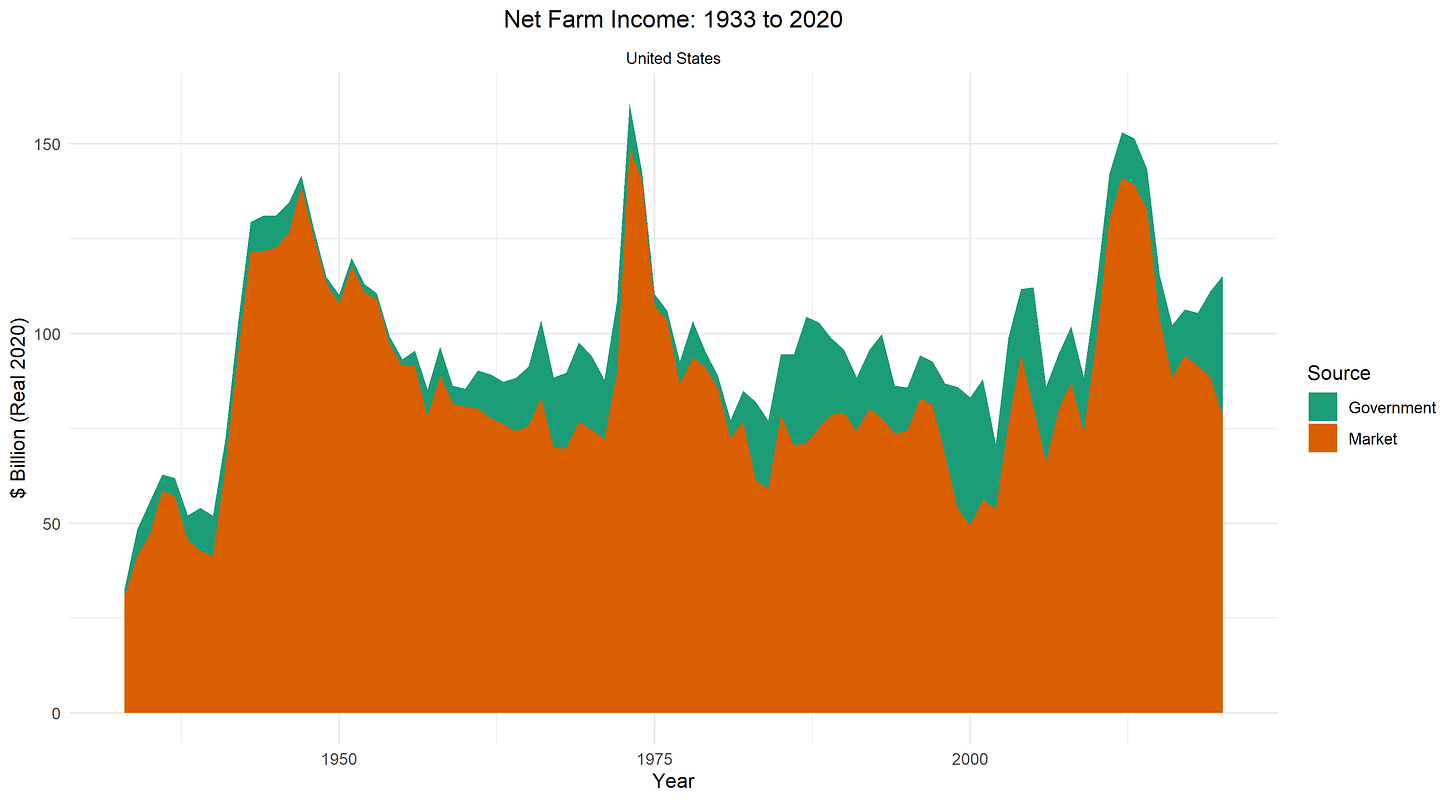

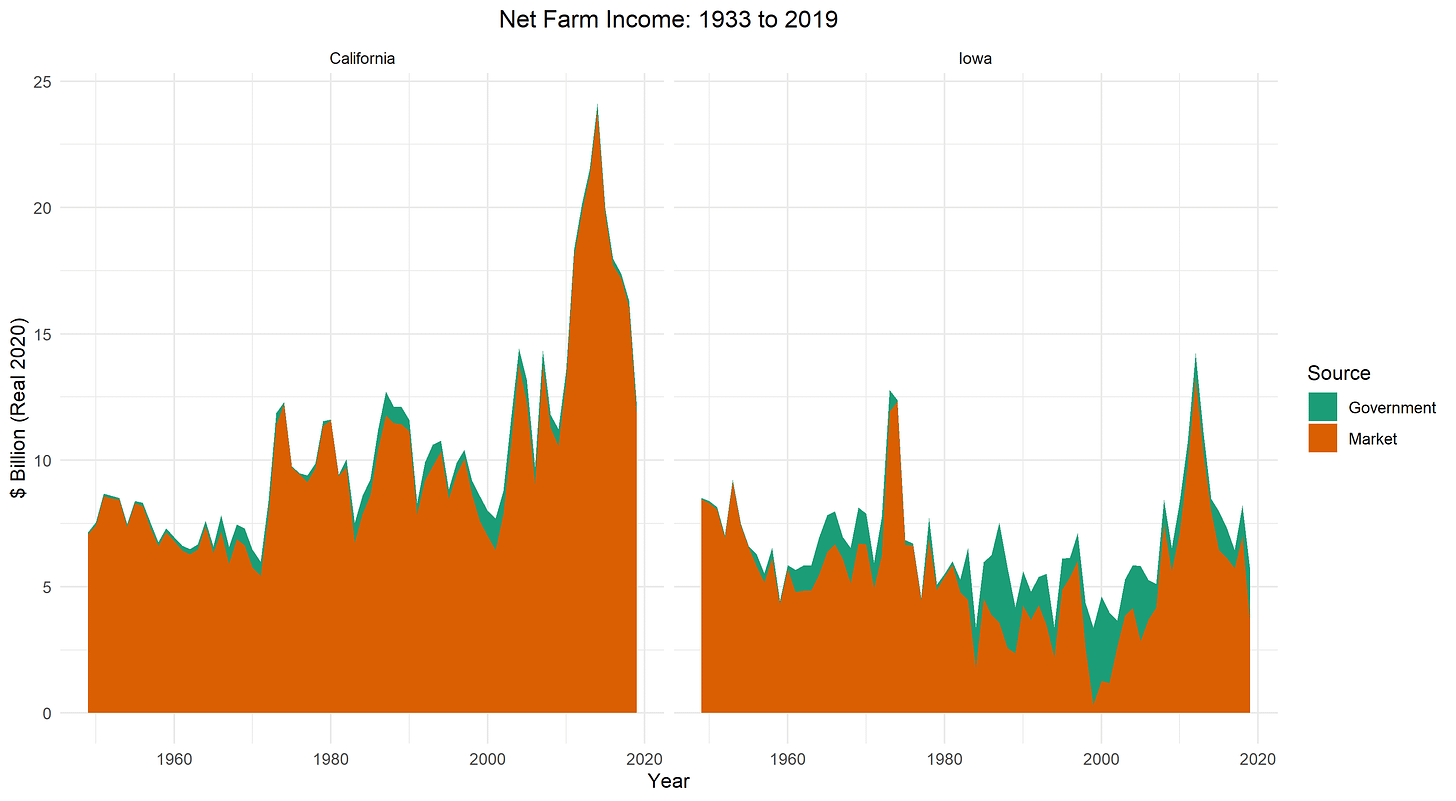

In 2020, USDA projects that government payments will be a third of net farm income. With this support, real net farm income will be higher than any year since 2015. Real net farm income this year will be lower than the boom years of 2011-2014, but it will exceed any other year since the 1970s.

Although US net farm income is high in 2020, there are significant differences across states. Tree nuts, in particular, have generated high profits in California in recent years. However, in Iowa, real net farm incomes are substantially below the prosperous levels that began in 2007 with the ethanol boom and persisted through 2018. In 2019, Iowa farmers made $5.6 billion, which is only slightly above the $5.3 billion average during the doldrum years of 1985-2005.

These state plots end in 2019 because the Economic Research Service of USDA has not yet published 2020 projections at the state level. It remains to be seen what 2020 net incomes will look like in these states, but the CFAP payments will certainly help.

Because government payments to farmers tend to focus on the major grains, they are distributed unevenly across states. California is a large state and the value of its agricultural production is about double that of Iowa. In 2019, Iowa farmers received $2.1 billion in aid and California received less than $0.5 billion. So far in 2020, California farmers have received about $1 billion and Iowa farmers about $1.5 billion in CFAP payments.

Representation in the US Senate skews rural relative to the population as a whole, President Trump has greater support in cornbelt states than coastal states, and Iowa occupies a unique spot as an early barometer in presidential election primaries. These features of the US political system may partially explain the high support payments in 2019 and 2020, or why relatively more farm support goes to corn than almonds.

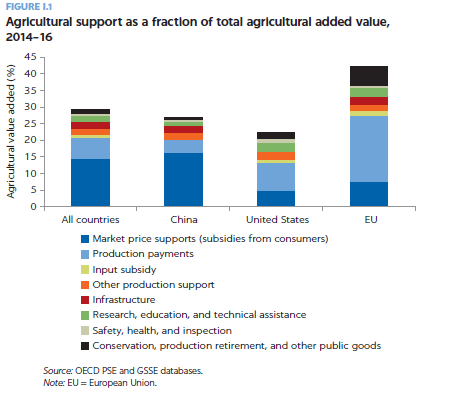

However, many countries support agriculture with direct payments to farmers, often at higher rates than the US. Thus, nuances of the US political system are an incomplete explanation for the high rate of support for farmers.

It doesn't have to be this way. In a future article, I will write about my home country of New Zealand, which eliminated direct payments to farmers in the 1980s. Their agricultural sector is better for it.

Postscript

The farm support data in this article do not include crop insurance subsidies, which have averaged about $7 billion per year since 2008. More on those numbers in a future article after we release our crop insurance data app.

We do not yet have a data app for farm income or government payments. I created the graphs in this article using R code that pulls data from spreadsheets posted on the USDA Economic Research Service website.

Link to code: govtsupport.R

Links to data sources: Government Programs, Farm Income