Government Intervention in India and Taiwan Affects Global Rice Markets

This article was written by UC Davis ARE PhD students Parth Chawla and Tzu-Hui Chen. It is the third of six excellent articles written by students in my ARE 231 class this fall.

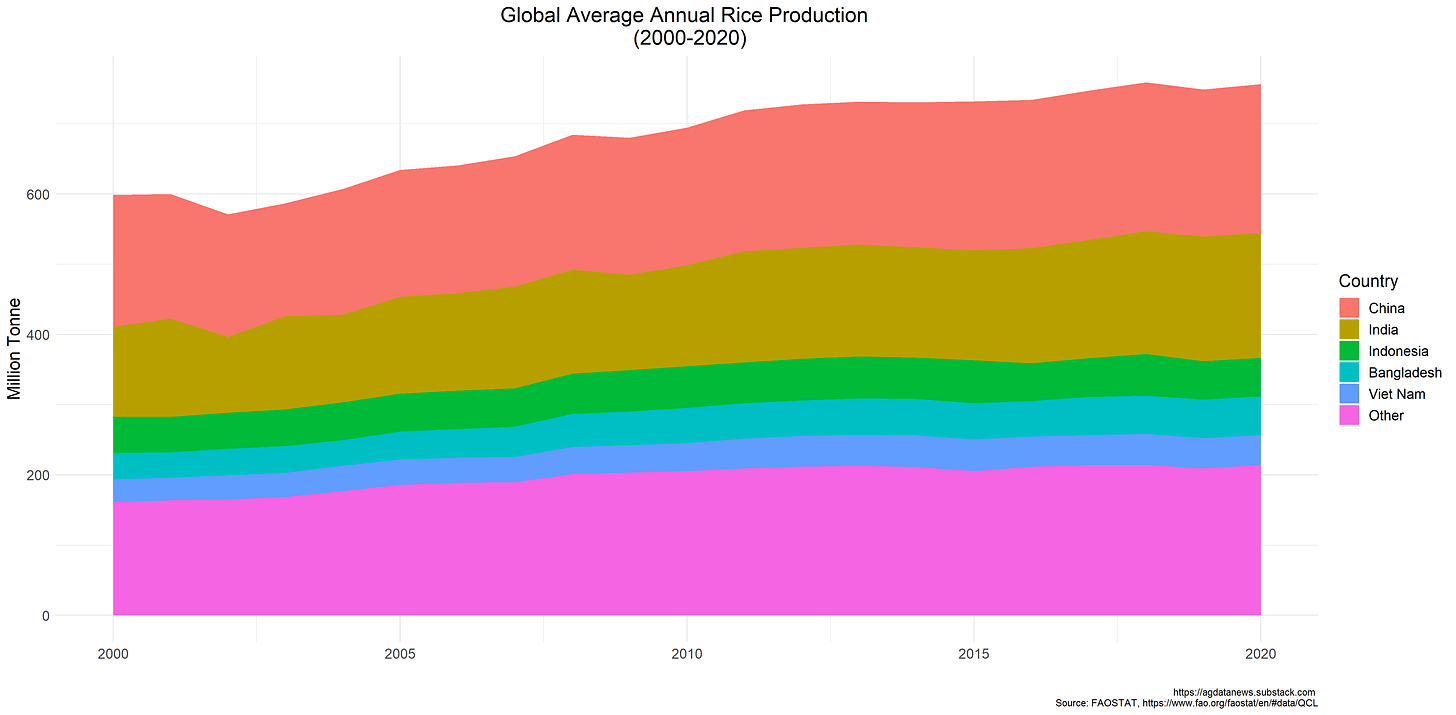

Rice is the third-highest produced agricultural commodity in the world and accounts for a fifth of the calories consumed by humans worldwide. As a staple food for several billion people, particularly in Asia and Africa, it plays an important role in the food security of the global poor. Governments around the world use various measures to maintain its supply and price.

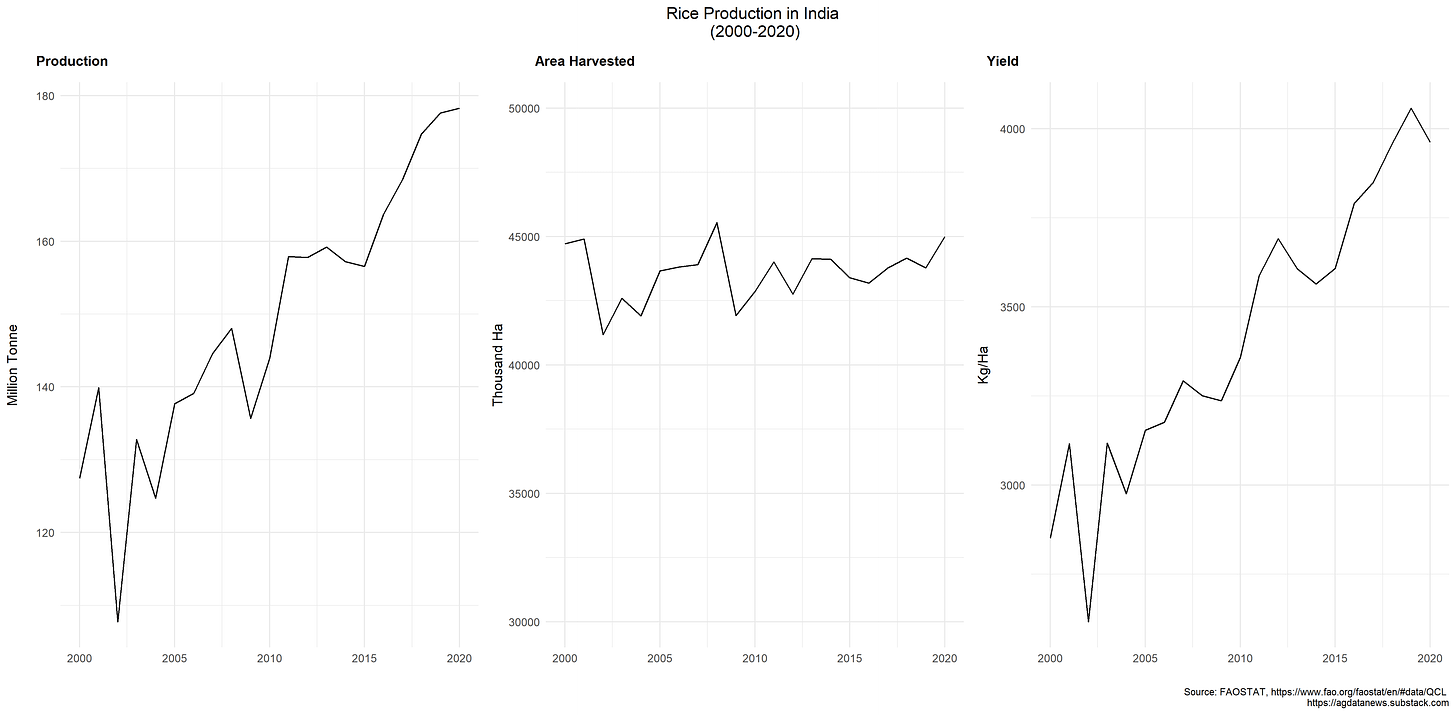

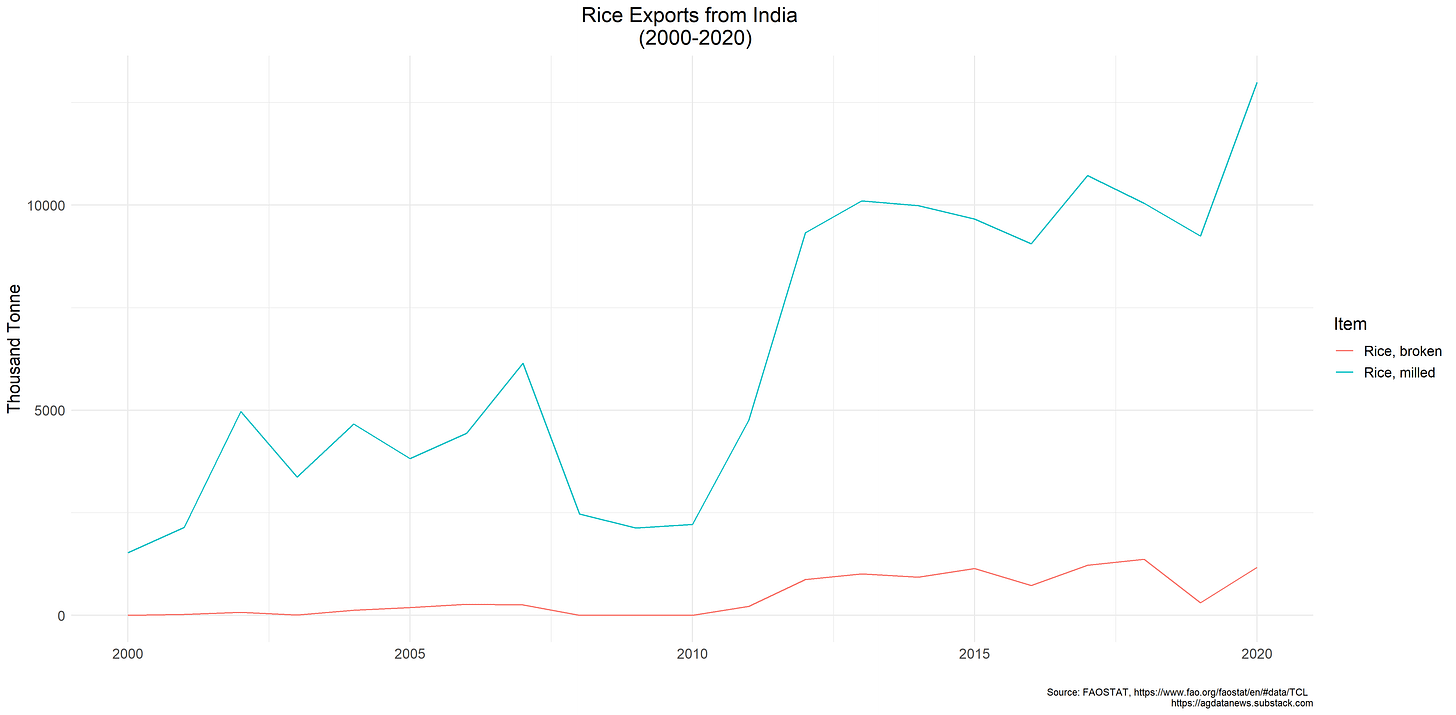

India is the second-largest producer of rice with a total production of 130 million metric tons (MMT) during the 2021-22 crop year. It is also the largest exporter of rice in the world accounting for 40 percent of global shipments. Despite a sharp increase in rice production from India from 2000-2020, the area harvested has remained relatively stable owing to a consistently rising yield.

The sharp rise in rice production in India over the past two decades can only be partly explained by the rise in exports. Production has increased by 50 MMT since 2000, but exports increased by only 10 MMT over the same period. Increasing population and domestic demand might also be factors driving the production increase.

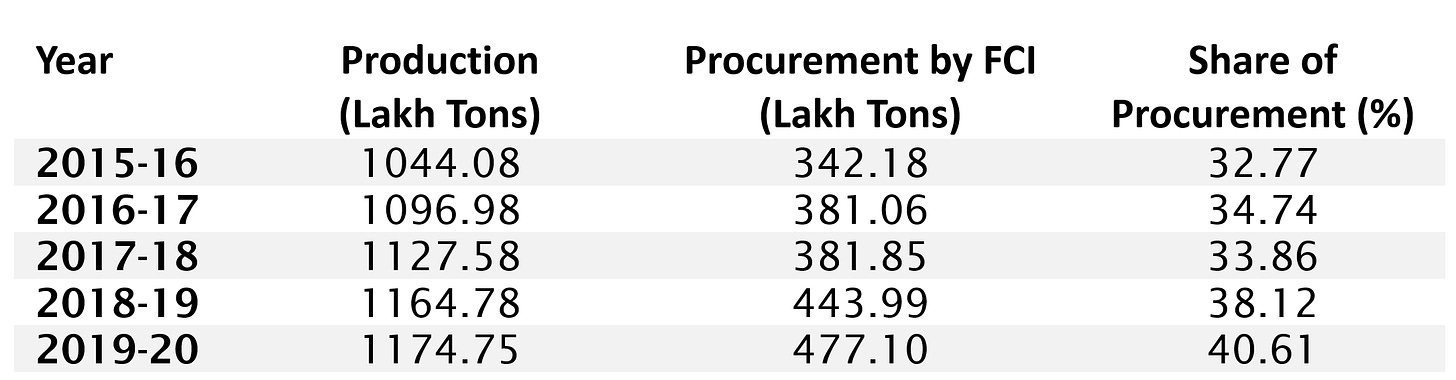

However, perhaps the most important factor is the incentives created by government. The Food Corporation of India (FCI) buys rice and other agricultural commodities from farmers at a minimum support price (MSP), set by the government on an annual basis. The MSPs act as price floors for farmers and ensure that domestic prices never fall below it.

The government essentially guarantees procurement at the minimum price every year, so it has built massive stockholdings of rice and other food commodities. These stocks are used by the government in their public distribution schemes to the poor. The MSP policy therefore allows the government to control the domestic price of rice and isolate it from fluctuations in the international price. Although there is significant geographic inequality in procurement by the FCI, the amount of rice procured in recent years amounts to over a third of all rice produced in India. Therefore, the policy has a large effect on rice production.

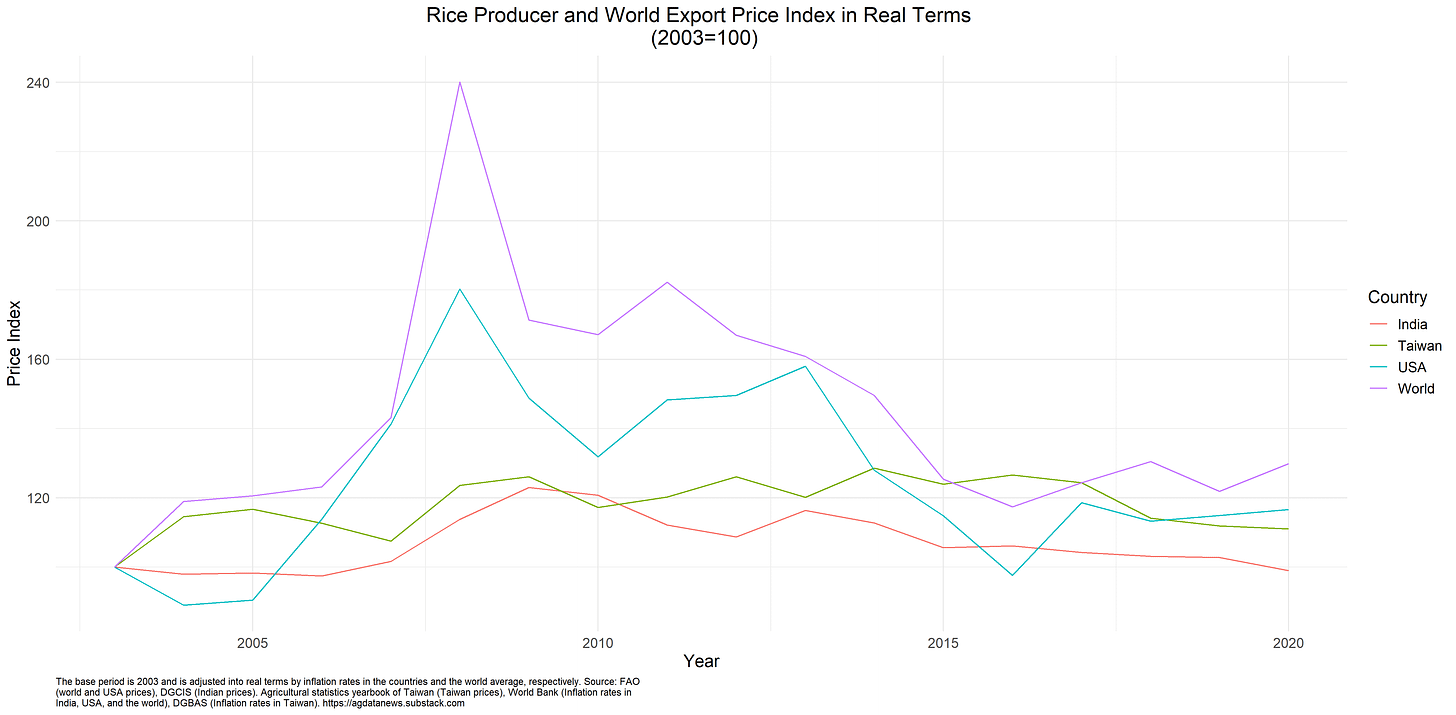

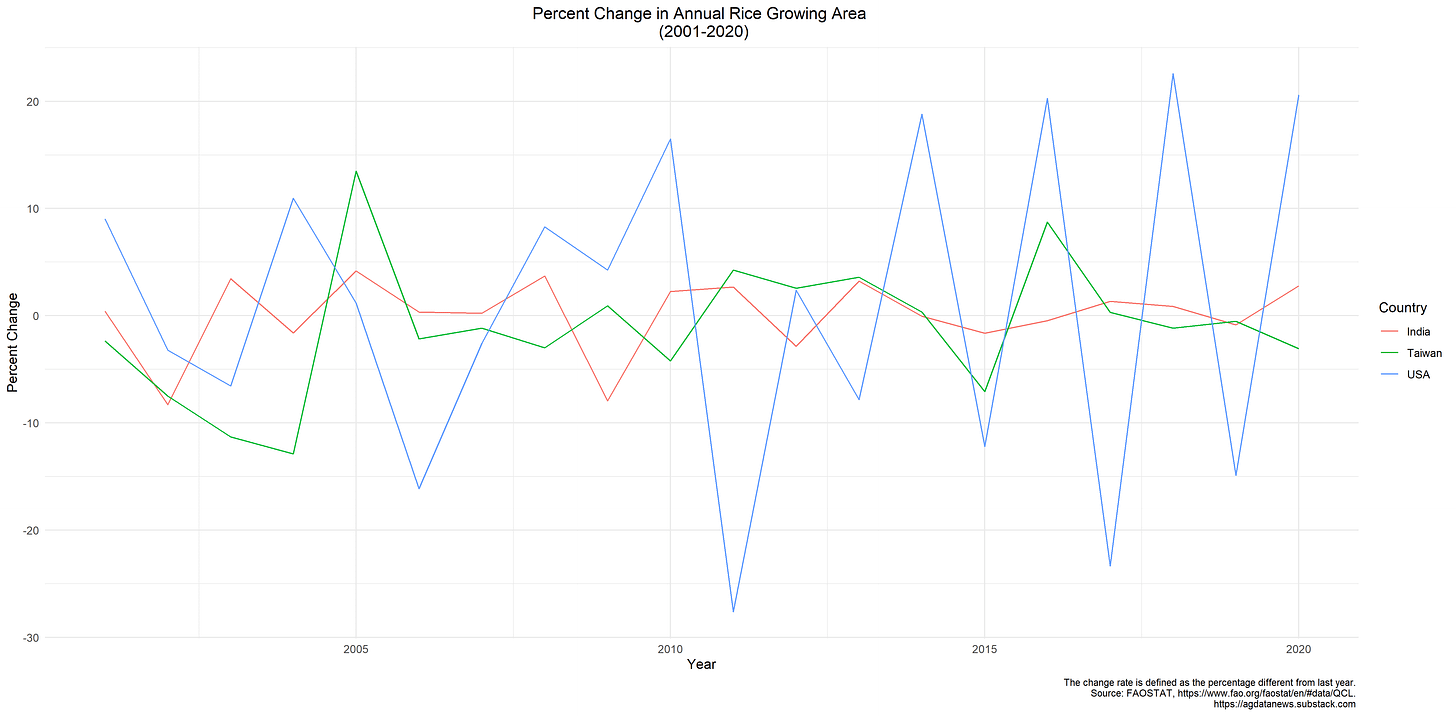

Farmers in India, and other emerging markets with similar government interventions, do not base their production decisions solely on market prices. The incentives created by government schemes play a huge role in their choices and might influence the prices themselves. This makes rice production and prices in India relatively more stable than an economy like the United States and explains why the area used for rice cultivation remains relatively steady.

Since India is the world’s largest rice exporter, the policies implemented by the government also affect the rest of the world. Indian government subsidies are passed onto to the international market in the form of stable supply and prices. That is one reason why rice prices haven’t been as volatile as other agricultural commodities in the past decade.

However, the reliance on India also exposes the international market to potential shocks. For example, this year in September, the Indian government banned the export of broken rice and imposed a 20 percent export tax on several other varieties. This might have huge implications for global rice prices and food insecurity in developing countries.

Taiwan is another example of a country where rice production isn’t as tightly connected to the international market because of government intervention. Producer prices in Taiwan have some correlation to the world price, but they are much more stable. Like in the Indian case, the change in the area harvested and prices for rice are also more stable in Taiwan than the United States.

Taiwan also has a price support program for rice, which has existed since 1974. Farmers can sell a fixed amount of rice per hectare to the government at a guaranteed price. Businesses are allowed to import and export rice freely since 2002, but they must pay an import tax if they exceed a quota (10 percent of total rice consumption). The tax is about twice the average world price per kilogram.

Under these conditions, farmers’ decisions aren’t influenced very much by global prices. Dramatic changes in production occur because of government policies, not prices. In 2021, the area harvested with rice dropped 14.4 percent compared to the previous year when the world price had only dropped by 0.23 percent. The major reason for the decrease in production was that the Taiwanese government had stopped about 20 percent of irrigation services because of a severe drought.

Markets for essential food commodities in many countries, especially developing countries that have an incentive to prevent fluctuations in these markets, get distorted by government intervention. The production decisions of farmers in these countries are largely determined by local government policies that either try to control the price directly or offer other incentives that make prices less important in the decision.

Separating production decisions from world prices can affect the incentive to invest in improving productivity and can have massive implications for the availability of food commodities to the world, especially in the case of large exporters like India.

Parth and Tzu-Hui made the graphs in this article using this R code.