Does Insulating Houses Reduce Energy Consumption?

Following the 1973 energy crisis, US policymakers sought to reduce fossil fuel consumption by mandating improvements in energy efficiency. In 1975, the federal government established minimum fuel efficiency (CAFE) standards for new vehicles. In 1978, California adopted the nation’s first state-level energy building codes, establishing minimum energy efficiency requirements for new buildings.

Nowadays, we frame energy efficiency mandates as climate policies because they aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel combustion. Perhaps the large increase in energy prices over the past two years will cause a return to the energy-crisis motivation.

Do these policies even work? Does requiring buildings to be insulated, for example, actually reduce energy use?

You might think the answer is an obvious yes, but prior studies found that residential building codes may not reduce energy use, let alone pass a cost-benefit test.

This week in Ag Data News, I highlight a research paper addressing this question. The paper, which I co-wrote with my colleague Kevin Novan and our former PhD student Tianxia Zhou, came out this month in the Review of Economics and Statistics. This is a slightly different topic from the usual Ag Data News fare, but it does contain a lot of data.

Now, some of you may be thinking "wait, haven't I heard about this before?" The economics publishing process is a long and winding road. We submitted the paper to this journal almost four years ago. We went through several rounds of review before it was accepted just under two years ago. So it's quite possible you heard about this paper. In fact, Meredith Fowlie wrote about it on the EI blog five years ago.

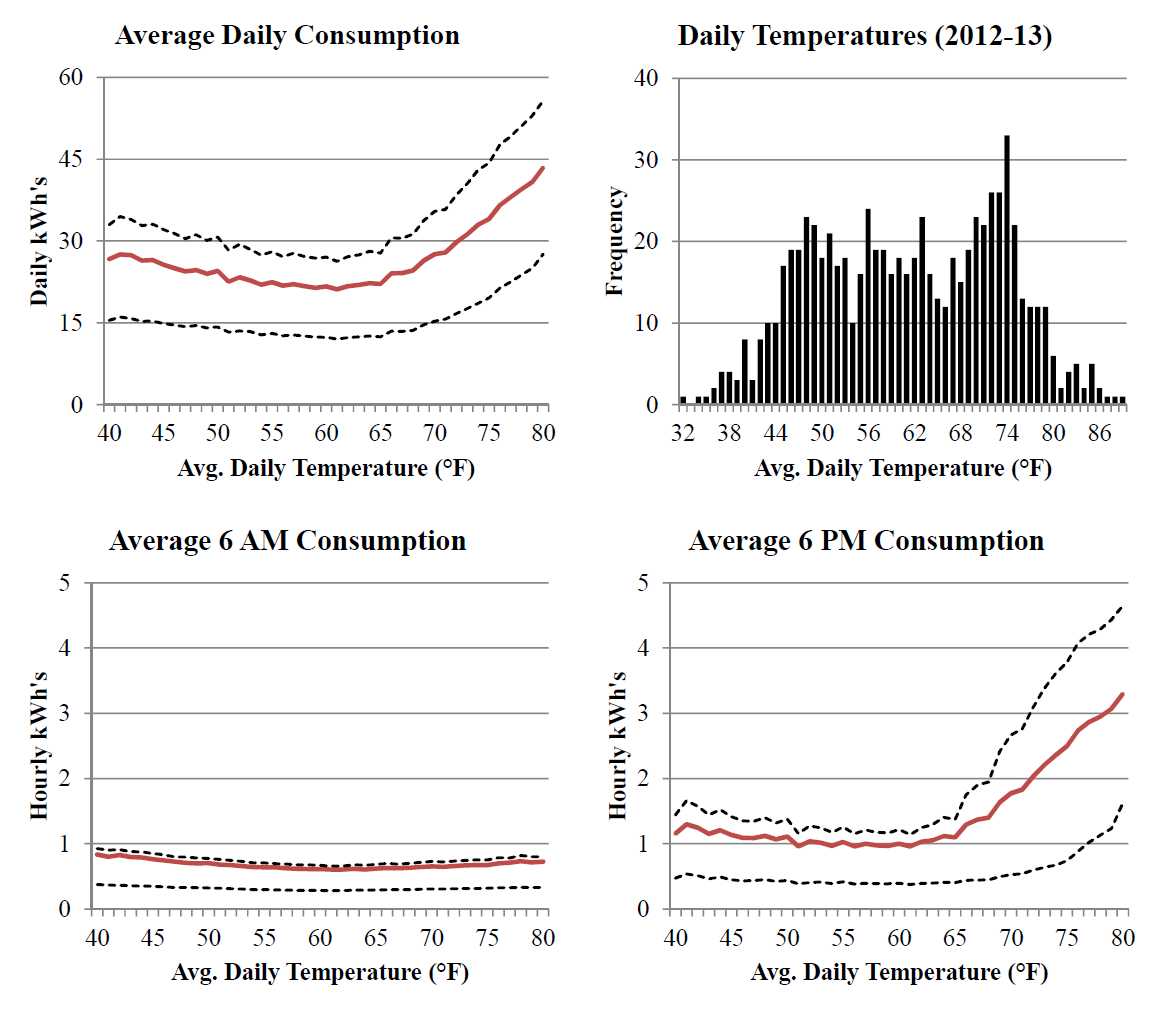

We use a rich dataset containing electricity consumption for every hour during 2012 and 2013 in 158,112 Sacramento houses. By using more granular data than other studies, we are able to see reductions in energy use that they missed.

Most of these houses use gas for heating, so electricity consumption is driven much more by air conditioning on hot days than heating on cold days.

California started requiring building codes in 1978. The codes specified minimum standards for wall, ceiling, and raised-floor insulation, allowable heat loss through windows, and the efficiency of climate control systems in new buildings. We ask whether houses built just after 1978 use less electricity when it gets hot than similar houses built just before 1978.

In Sacramento, an average daily temperature of 62ºF implies a high of about 75ºF and a typical day with an average of 80ºF will reach 100ºF. When the average daily temperature moves above 62ºF, electricity consumption increases by less in the post-building code houses. They require less energy for air conditioning.

We estimate that the average house built just after 1978 uses 8% to 13% less electricity for cooling than a similar house built just before 1978. These reductions occur in the late afternoon or early evening on hot days.

Comparing the estimated savings to the policy’s projected cost, our results suggest the policy passes a cost-benefit test. In settings where market failures prevent energy costs from being completely passed through to home prices, building codes can serve as a cost-effective tool for improving energy efficiency.

Our analysis takes advantage of the long-lived nature of the housing stock; we estimate energy savings more than thirty years after the codes were adopted. The durability of the housing stock also underscores the importance of ensuring that society is not underinvesting in the energy efficiency of new houses.

Here ends our detour from agriculture into electricity. Regular programming resumes next week.

Kevin Novan, Aaron Smith, Tianxia Zhou; Residential Building Codes Do Save Energy: Evidence from Hourly Smart-Meter Data. The Review of Economics and Statistics 2022; 104 (3): 483–500. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00967