Changing Ethanol Policy Isn't Going to Help

How do you know if your industry is a political football?

Answer: people think the solution to the latest crisis is to change the policies regulating your industry.

To counteract high gasoline prices, ethanol advocates have proposed relaxing restrictions limiting the percent of ethanol that can be blended into gasoline. Their theory is that ethanol is cheaper than petroleum, so using more of it will lower gasoline prices.

To counteract high wheat and corn prices ethanol opponents have proposed waiving or eliminating the ethanol mandate. Their theory is that ethanol is more expensive than petroleum, so removing the ethanol mandate will allow more corn into the food system thereby reducing food commodity prices.

Who's right?

Answer: Neither of them. They're both wrong. Neither policy would do much of anything to gas or food prices.

Ethanol has a long history as a motor fuel. In 1920, the U.S. Geological Survey estimated that peak petroleum production would be reached within a few years. Two years later, Henry Ford advocated for using ethanol as fuel. At the time, corn prices were low because European supply had recovered after being decimated during World War 1.

There is fuel in corn; oil and fuel alcohol are obtainable from corn, and it is high time that someone was opening up this new use so that the stored-up corn crops can be moved.

Then they discovered cheap oil in Texas. Ethanol disappeared until 1970s when oil got expensive again, but it didn't become significant until the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) mandates in the 2000s. For more background, I highly recommend episode 2 of the Corn Saves America podcast. (Listen to all the episodes, but episode 2 covers the ethanol origin story.)

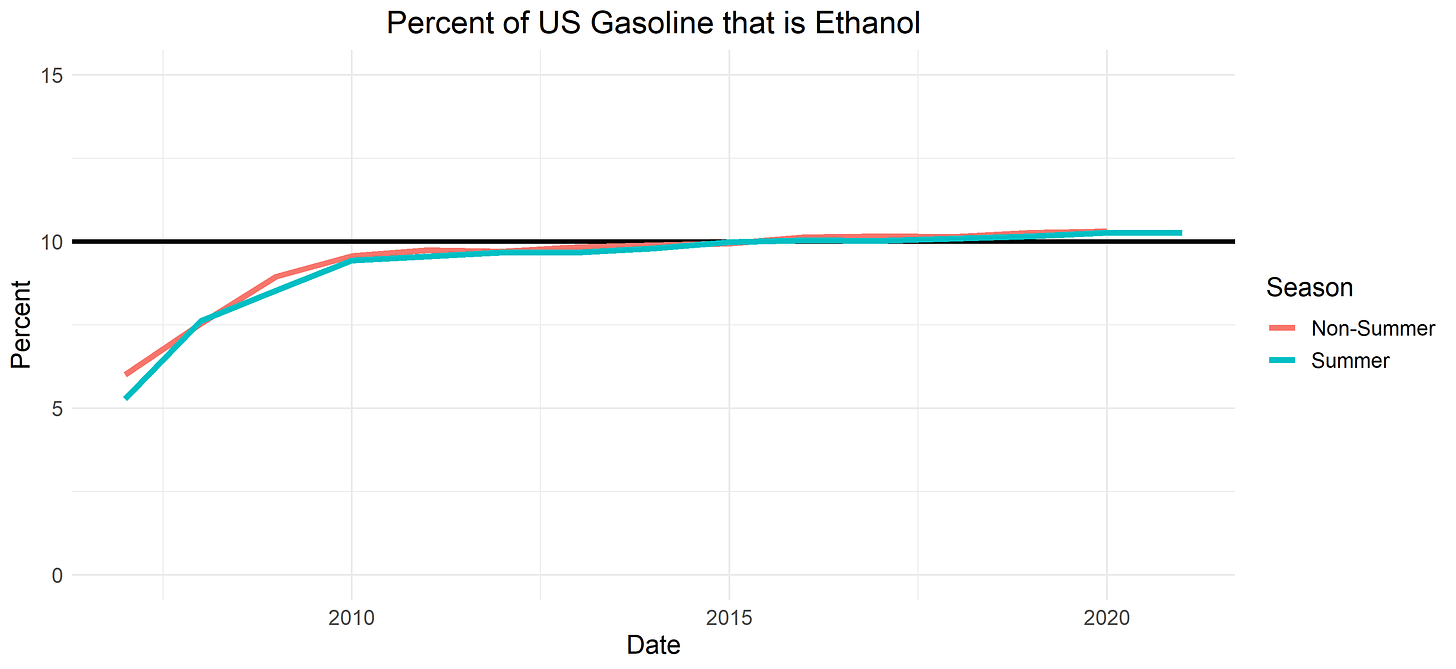

Under the RFS, about a quarter of US corn is used to make ethanol, which makes up 10% of US gasoline.

What are ethanol advocates proposing?

They want Congress to allow ethanol to be blended up to 15% year round (a fuel known as E15). EPA tried this in 2019, but it was overruled by the courts on the grounds that it violated provisions in the Clean Air Act.

Ethanol advocates imply that approving year-round E15 would increase the ethanol blend from 10% to 15%, replacing expensive gasoline and reducing prices at the pump. However, ethanol blends are only limited to 10% in the summer (June 1 through September 15) and only in conventional gasoline markets, which cover about two thirds of the country. In other markets, suppliers can blend up to 15% year round.

In the non-summer months when higher blends would be allowed, the total blend was a hair over 10% in 2020 and 2021. Allowing E15 in the summer would not change this.

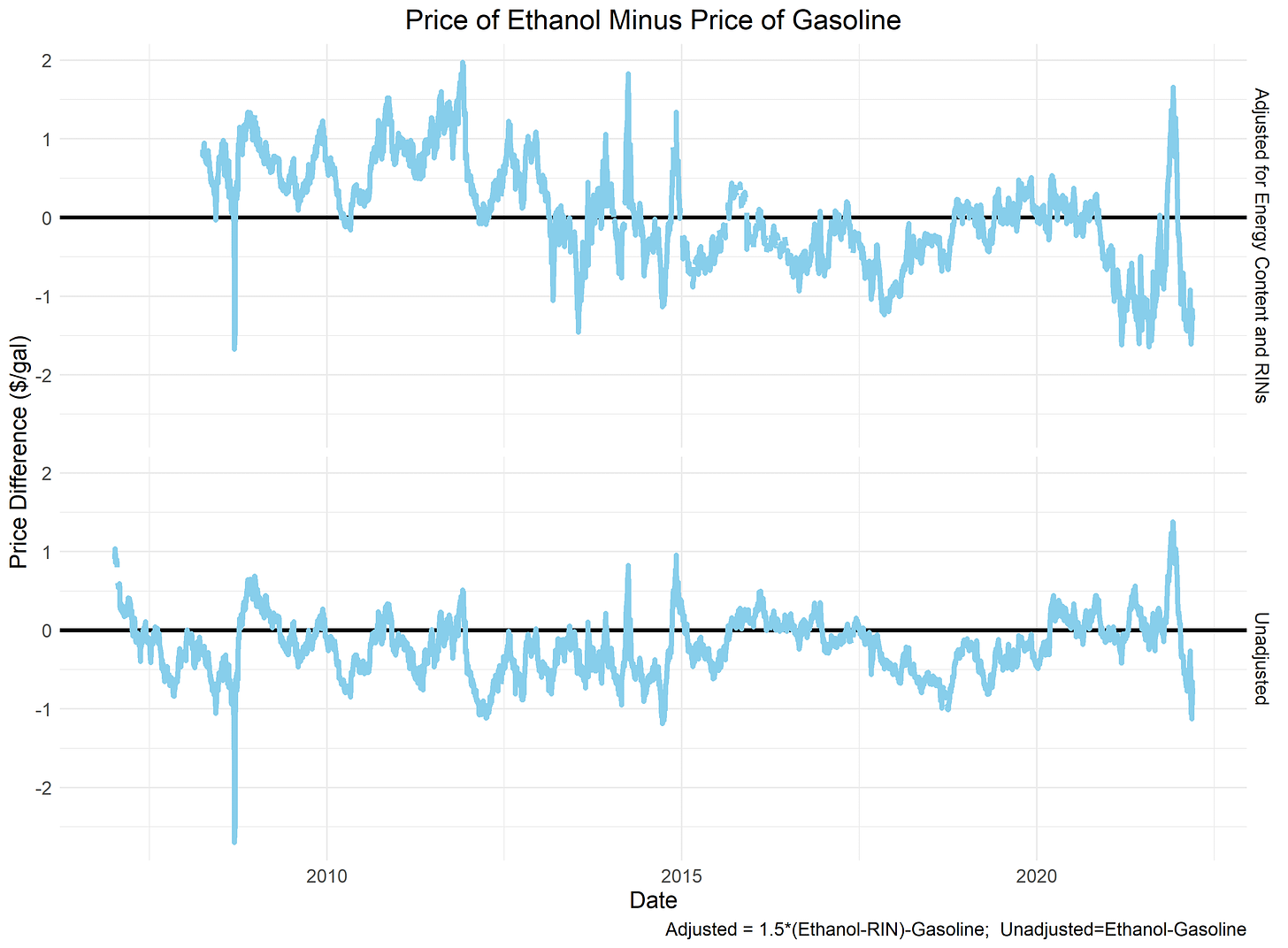

The recent increase in gas prices does not change these facts. Ethanol prices have been below gasoline prices for much of the last 15 years. Fuel suppliers did not voluntarily expand ethanol blends in 2018 when ethanol was 70c cheaper than gasoline, which suggests they would not do it now.

Two factors mean this comparison of ethanol and gasoline prices is not quite right. First, a gallon of ethanol contains a third less energy than a gallon of gasoline. Second, blending ethanol into gasoline allows suppliers to earn RFS credits (RINs). After adjusting for these factors, ethanol in 2022 is no cheaper relative to gasoline than it was in 2021.

A cynic might hypothesize that ethanol advocates want first to legalize year-round E15 after which they will push to mandate it. Expanding the ethanol mandate would be bad policy.

What are ethanol opponents proposing?

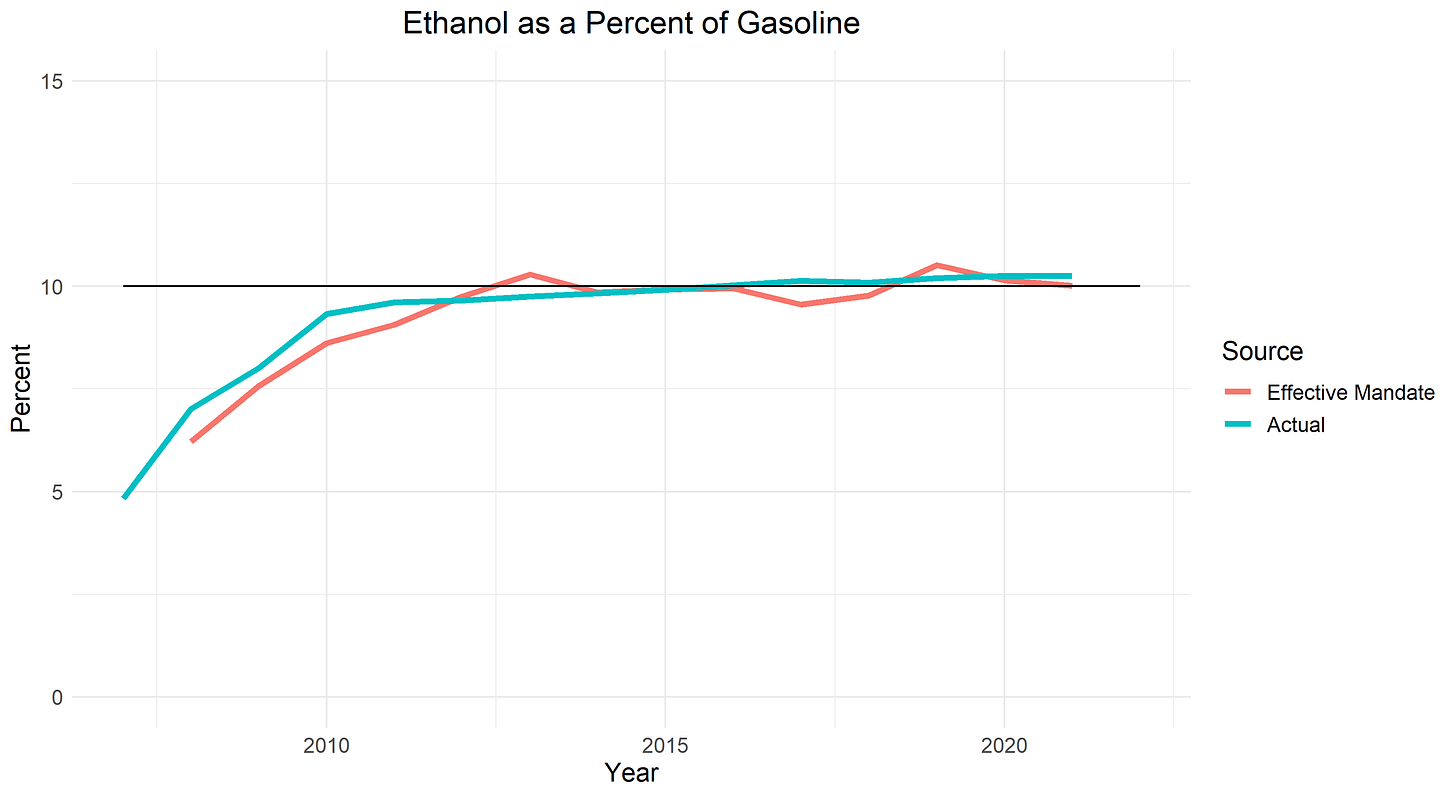

They want the RFS to go away. However, eliminating the RFS would not change the ethanol blend rate in the short term. Refiners have adapted to blending ethanol at 10%. They use it as a cost-effective octane enhancer.

They had an opportunity to reduce ethanol blending in 2017 and 2018 when the EPA exempted "small refiners" from complying with the RFS. These exemptions totaled 8.6% of the petroleum fuel supply in 2017 and 6.7% in 2018, and thereby reduced the mandate by these same percentages. The industry could have blended below 10% in those years but it chose not to.

So, please, leave ethanol out of the discussion of how to respond to the fallout from Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

I made the figures in this article using this R code.