Discover more from Ag Data News

Big Drop in California Rice Acres

On Monday, the USDA published the year's first data on which crops farmers have planted this year, which allows us to assess the effects of the ongoing drought on California crop acres.

The data contain two pieces of information that indicate how the drought is affecting land use. First, farmers report prevented-planting acres, which is land they had intended to plant a crop but were prevented from doing so by a natural disaster, such as inadequate irrigation water. Second, farmers report fallowed or idle acres, which is cropland not planted to a crop.

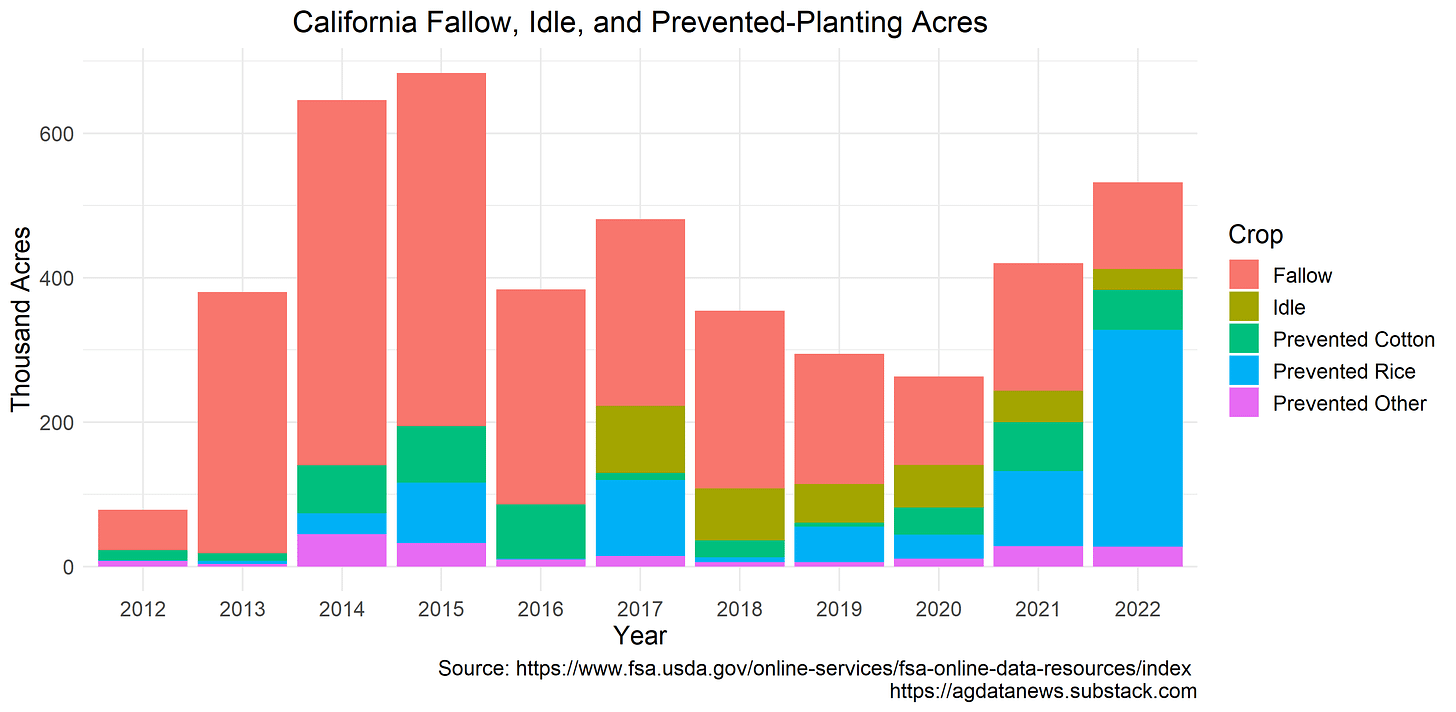

The reported number of unplanted crop acres in California is 532,000, which is an increase of 112,000 acres from 2021. Total unplanted acreage is about 7% of the state's cropland, but it remains lower in 2022 than it was at the height of the previous drought in 2014-15. Most of these acres came from prevented planting of cotton and rice.

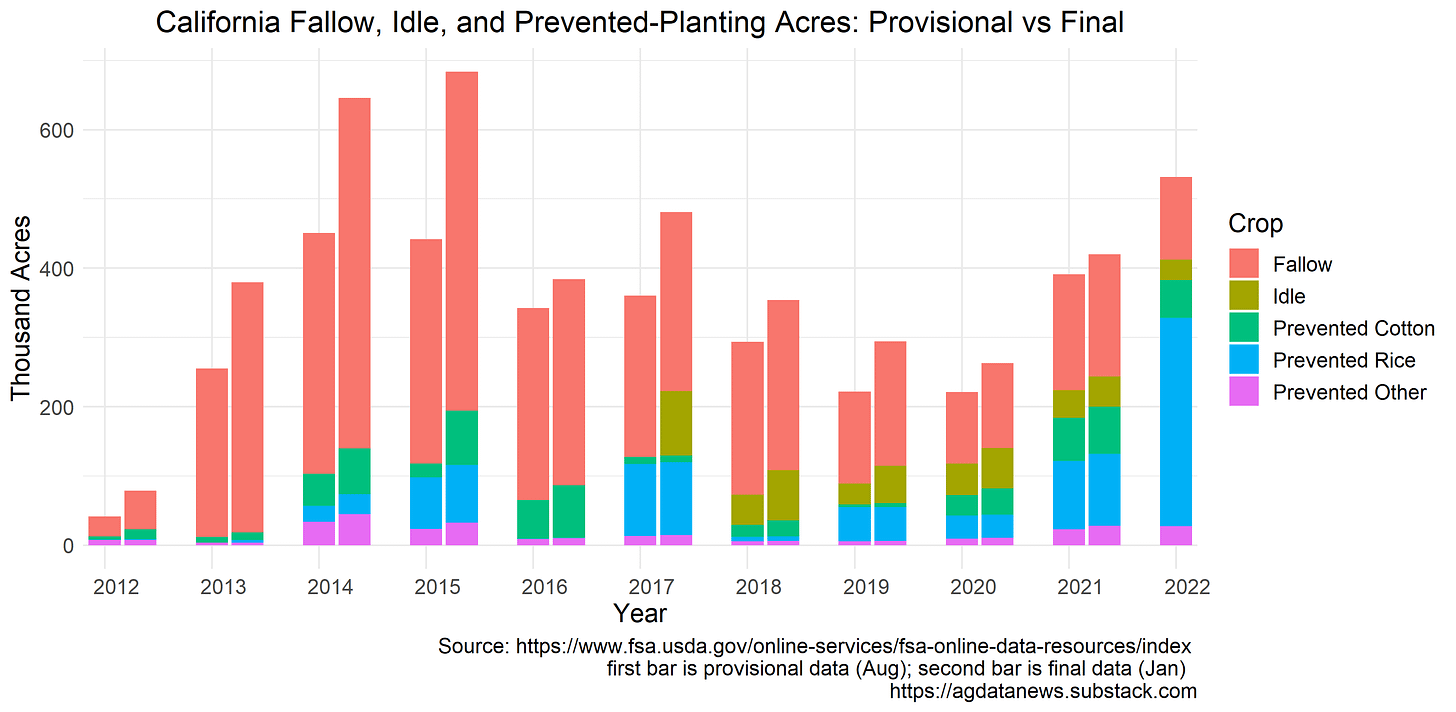

These data are provisional. They will be updated each month until the final numbers are released in January. The final numbers have exceeded the provisional every year since 2012. In the previous drought in 2014-15, the provisional estimates were revised upwards by about 200,000 acres. A similar revision this year would put 2022 fallow, idle, and prevented-planting acres above 2014-15.

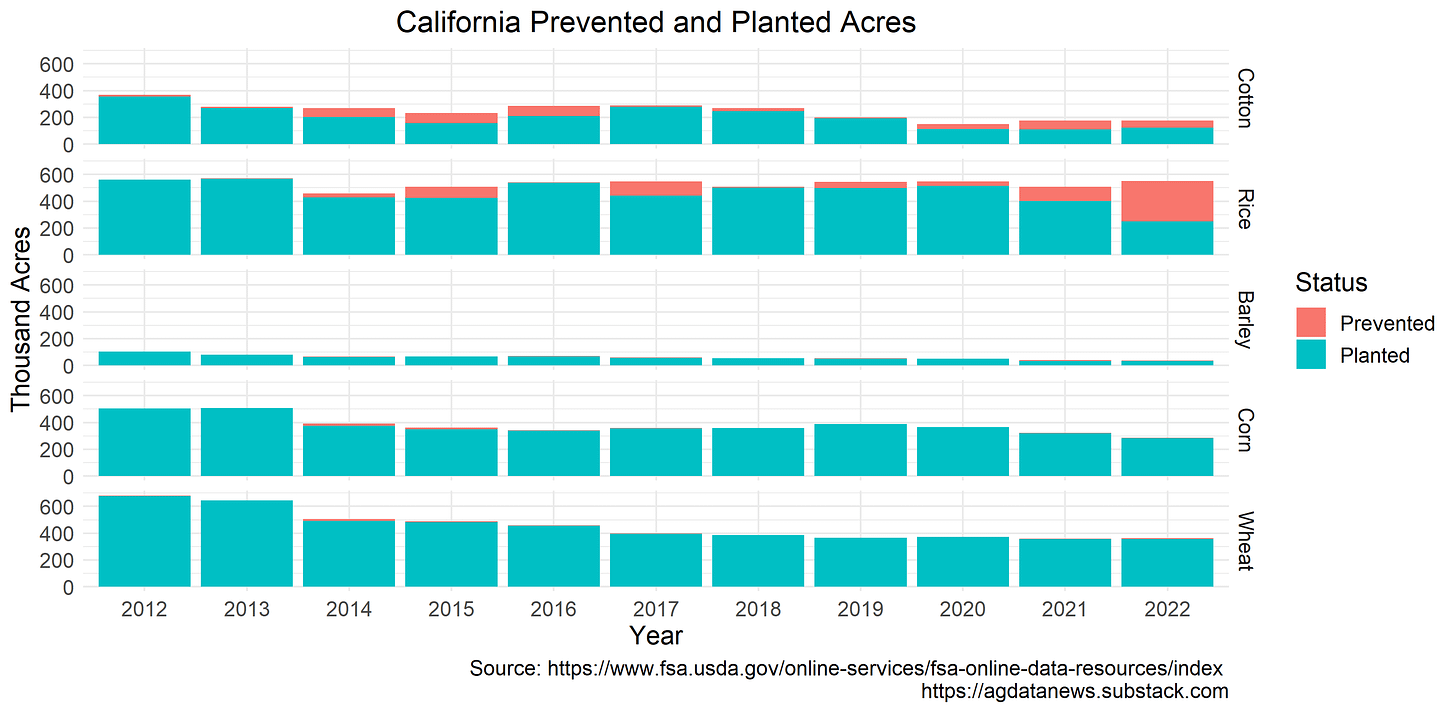

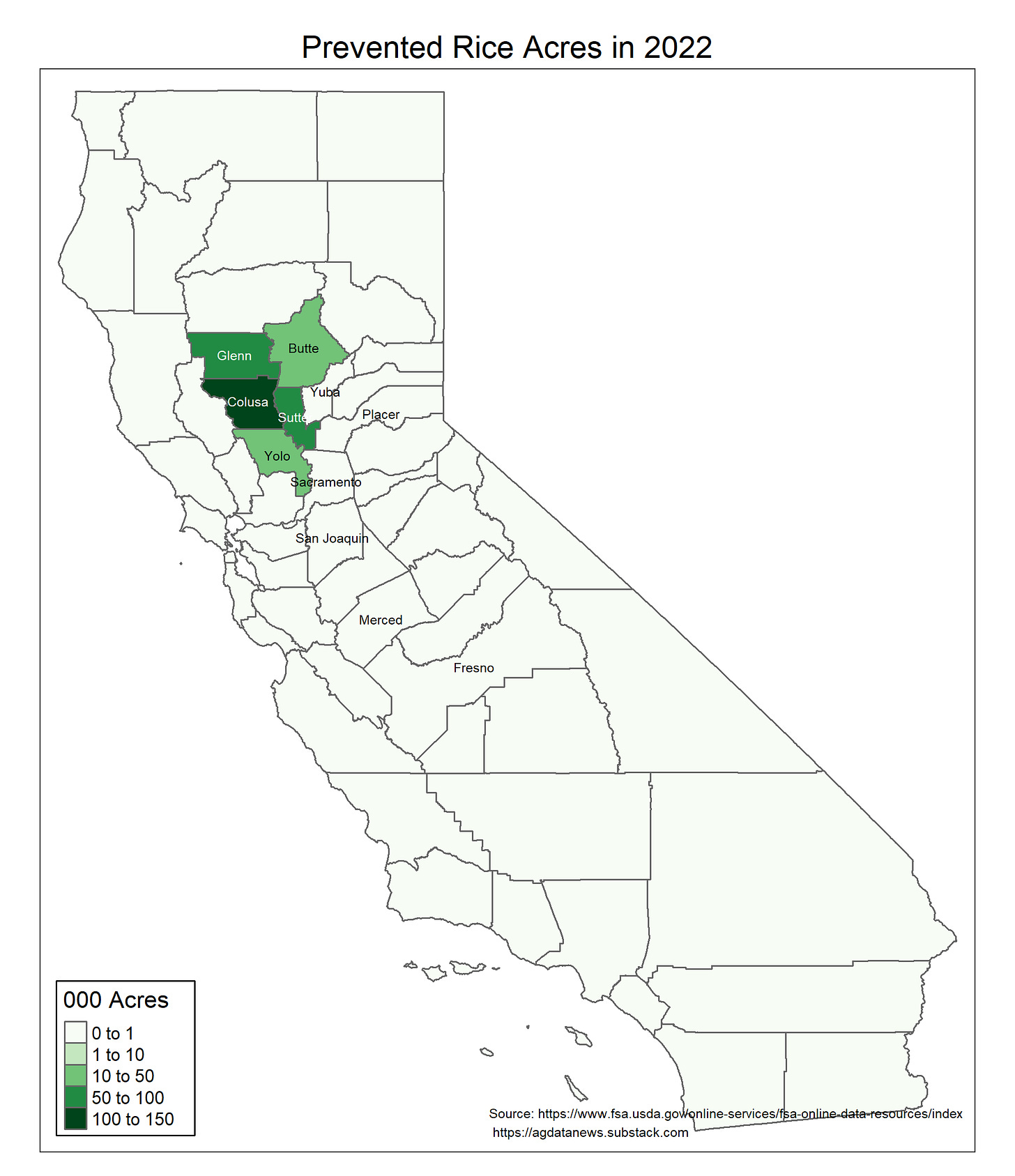

Prevented planting reduced rice acres by 55% in 2022, which is much larger than observed in any other crop in recent years. There were almost no 2022 prevented-planting acres in California crops other than cotton or rice.

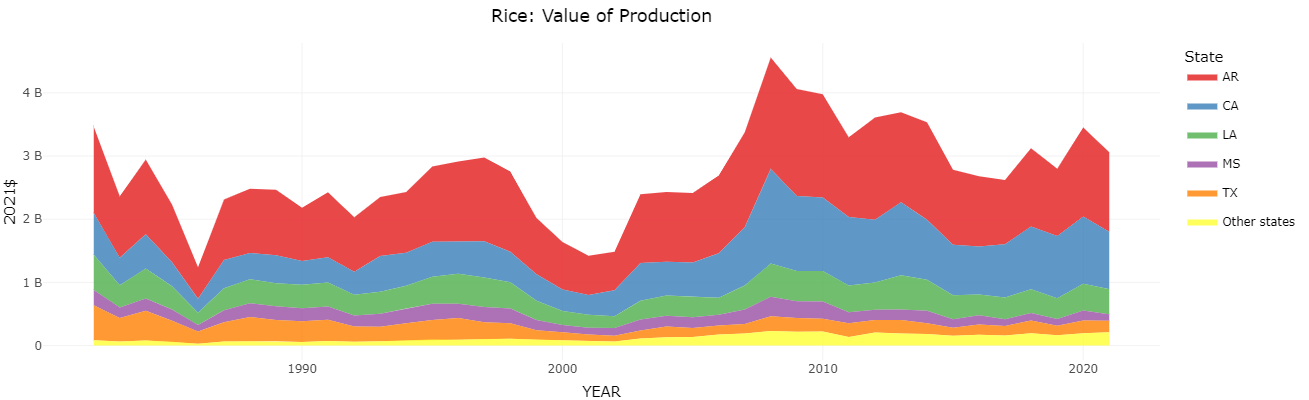

This is a big reduction in US rice production. California is the second largest rice-producing state behind Arkansas, producing about $900 million in production value per year. Most California rice is medium-grain Japonica for use in Asian and Mediterranean dishes such as sushi, paella, and risotto. Other US states produce mostly long-grain rice. In a typical year, about half of California's rice production is exported.

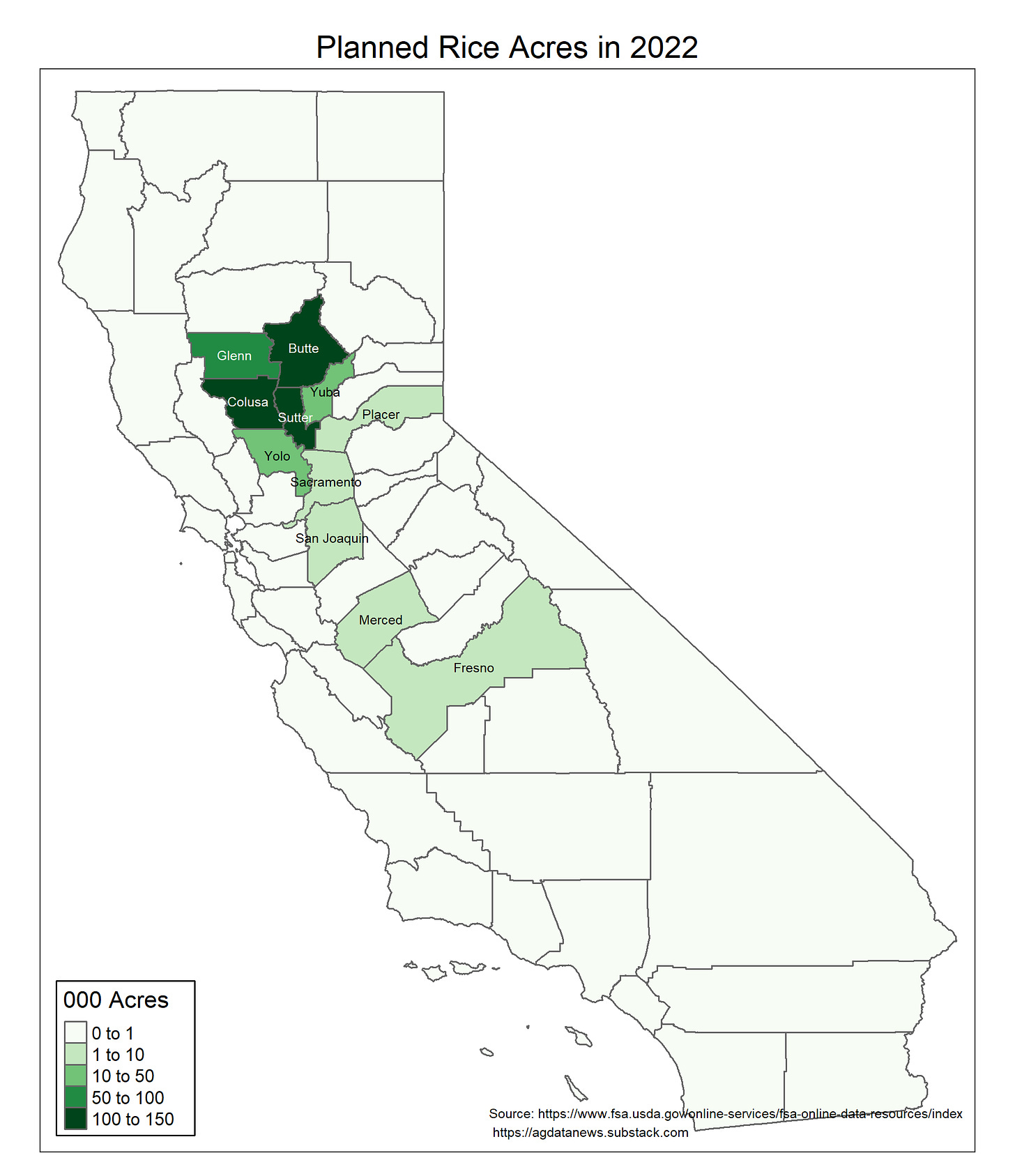

Most California rice is grown in the northern Central Valley. Farmers planned to plant more than 100,000 acres in each of Butte, Sutter, and Colusa counties this year. Small quantities of rice are grown as far south as Fresno county.

The drought reduced rice acres more in the western counties than those further east. Colusa County lost 84% of its acreage and Glenn lost 75%, whereas Butte lost just 17%. Butte County has greater groundwater resources, so it was less affected by reduced allocations from the Central Valley Water Project. These acreage reductions imply a market revenue loss of about $500 million, about 40% of which will be covered by crop insurance (more on that another time).

Update (8/25/22): Butte County rice growers also got Feather River water, which was curtailed much less than the CVP water from the Sacramento River (h/t @WadeWarrens on Twitter)

These data come from the Farm Service Agency (FSA), the part of USDA that administers farm programs. FSA requires all farmers who participate in crop insurance, farm credit, or disaster programs to report all cropland use on their farm. Thus, they represent only a subset of acres. Last year, I compared the acreage numbers from FSA to two other sources for several crops using data from our California Crops data app.

All three acreage numbers are quite close for rice, which implies that the FSA's prevented-plant data are a good estimate of how many rice acres the state lost this year. The FSA acreage numbers are less comprehensive for many other crops, especially perennials such as almonds, grapes, and pistachios, so they reveal little about the 2022 responses of farmers to the drought. It is possible there were acres outside of the FSA umbrella that were taken out of production.

In addition to prevented planting, FSA records both fallow and idle land. Fallow land is an intentional part of a rotation, e.g., a farmer may plant tomatoes, cotton, and fallow in a three-year cycle, with the fallow year intended to let the field "recover its fertility and conserve moisture for crop production in the next growing season". Idle cropland on the other hand, is just land not planted.

Fallow and idle acres have declined in recent years, perhaps partly due to acres the were formerly in row crops being planted to tree nuts. You can't temporarily fallow or idle an almond orchard.

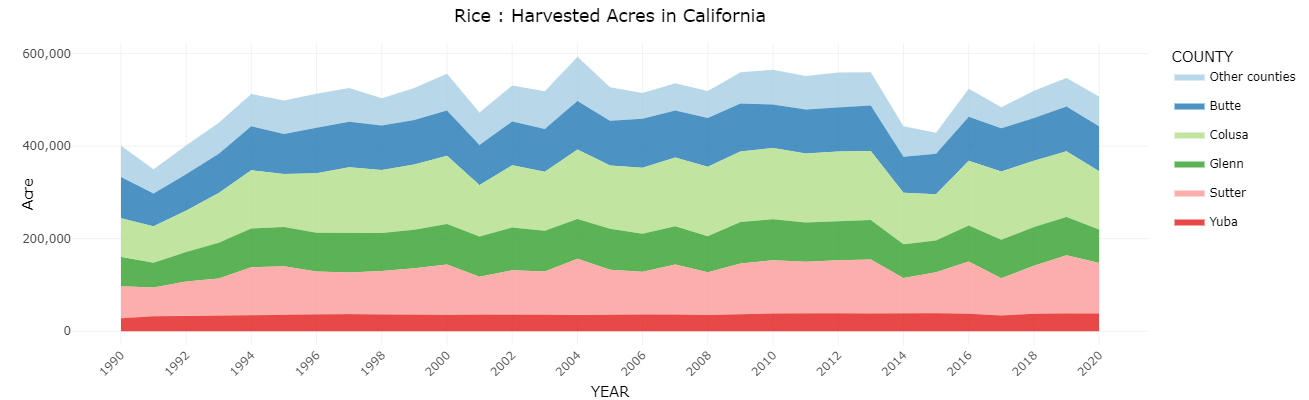

The growth of almonds and pistachios, along with the increasing scarcity of water, has been pushing crops like alfalfa, cotton, and wheat out of the state. Rice acres have been more resilient, dropping in the 2014-15 drought, but reverting back to previous levels by 2020.

Rice acreage will likely rebound again once this drought ends, but this year's massive reduction feels like a harbinger of tough times ahead for California rice.

The head picture in this article was created by AI. I typed "a dry California rice field on a hot day with an empty irrigation canal running through it and a sad farmer nearby" into DALL-E and that is one of the four pictures it generated.

I made some of the figures in this article using this R code and pulled others from our US Crops and CA Crops data apps. Use these apps to view or download agriculture data from the comfort of your web browser.