Discover more from Ag Data News

Agricultural Prices Aren't Driving Food Price Inflation

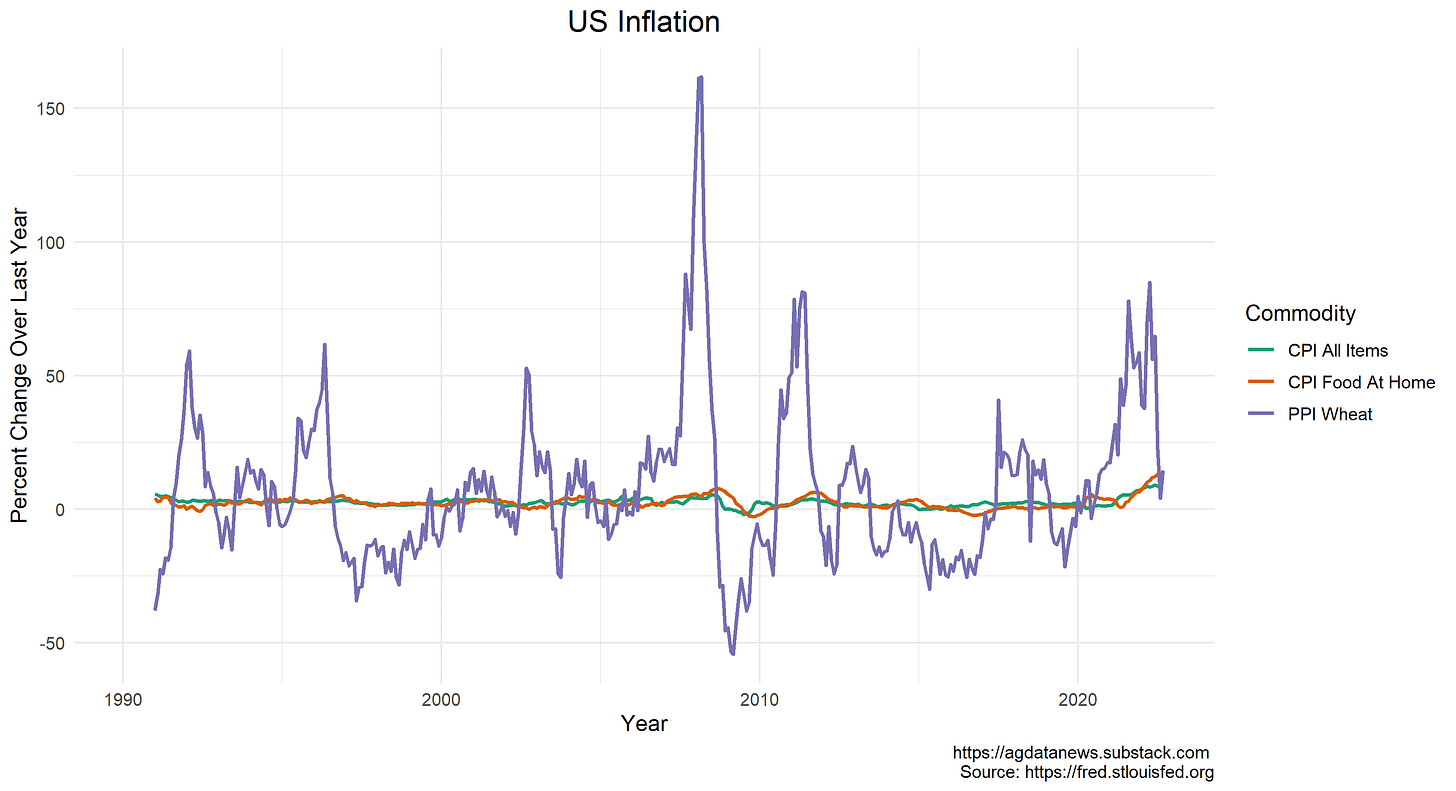

Prices in the grocery store have increased in the past two years, and it seems reasonable to look at the prices of agricultural commodities such as corn and wheat for signs of where food inflation is going. We have all read countless articles asserting that Russia's invasion of Ukraine caused grain prices to spike (a dubious assertion in itself), which means Americans will now face high bread prices.

Most of the price of food is processing, packaging, transportation and marketing. Agricultural commodity prices jump all over the place, but they have relatively small effects on grocery store prices. Annual wheat price inflation has ranged from -50% to 150% in the past 30 years with only minor implications for consumer food prices.

I am not the first to make this point. Cortney Cowley and Francisco Scott of the Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank made it very well in a recent blog post and associated video.

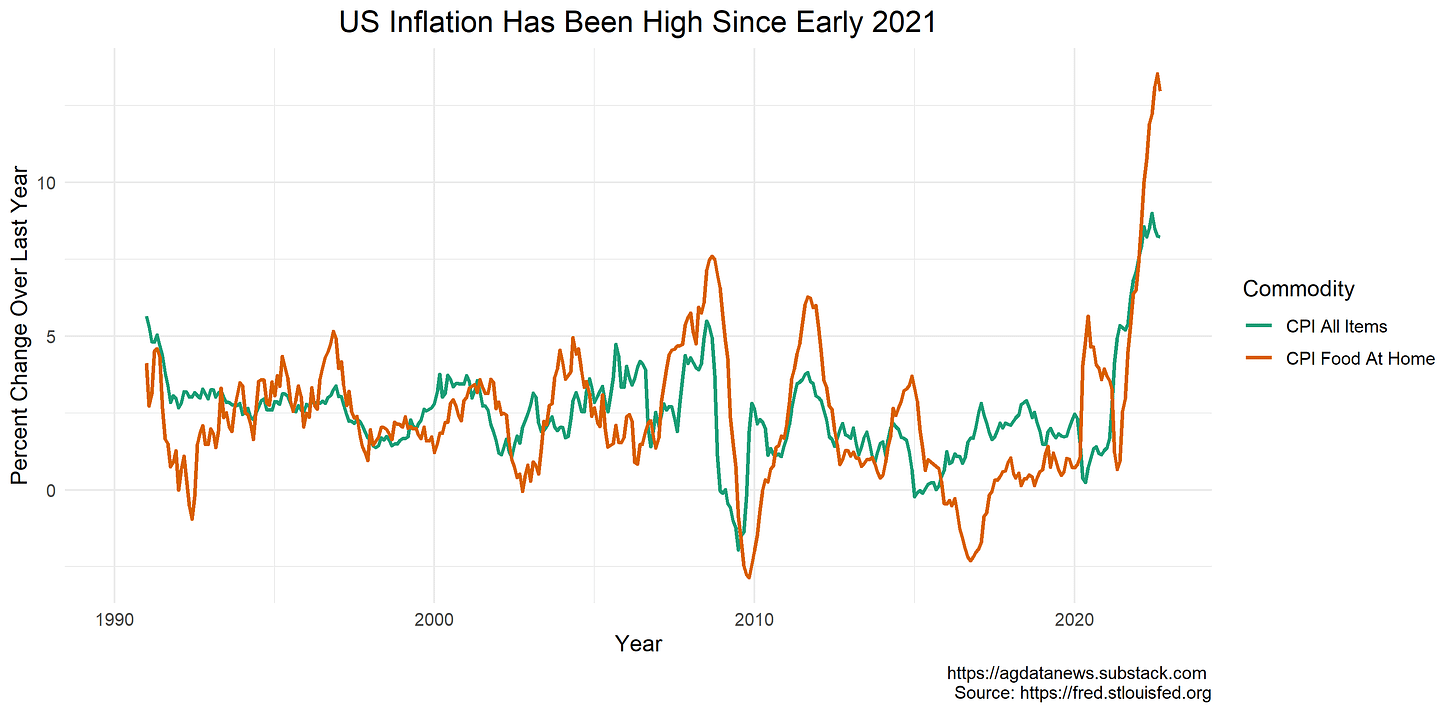

Yet, it is true that food price inflation is high. The consumer price index (CPI) for food at home is up 13.0% in the past year, whereas the CPI across all items is up 8.2%.

So, what is going on with food prices? Are they going to come down?

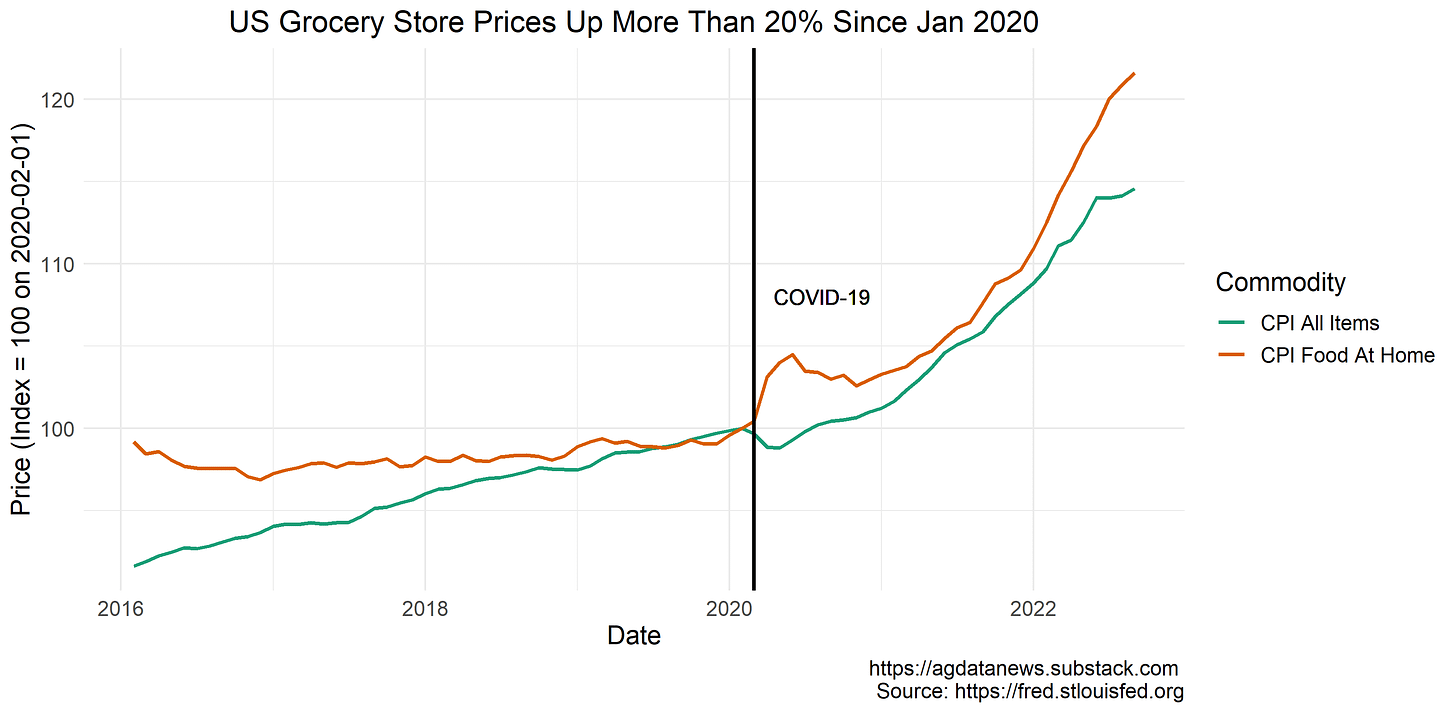

At this point, I am going to switch to showing prices rather than inflation. Economists often focus on inflation, which is the rate at which wages and prices throughout the economy are increasing. Normal people care about prices: do the things I want to buy cost more than they used to?

Imagine climbing a hill. Think of the price as your current elevation. Inflation is how steep the hill is where you are currently standing. In the past two years, the CPI for all items has climbed to a great height (high prices) and reached a plateau (low current inflation). The plateau is likely only a brief respite.

Since January 2020, grocery store prices are up 22%. Over the same period, the all items index is up 15%, which tells us that food prices are up more than other goods and services. Food prices jumped up at the beginning of the pandemic due to supply chain issues. By mid 2021, they were almost back to the level of other prices before they accelerated again.

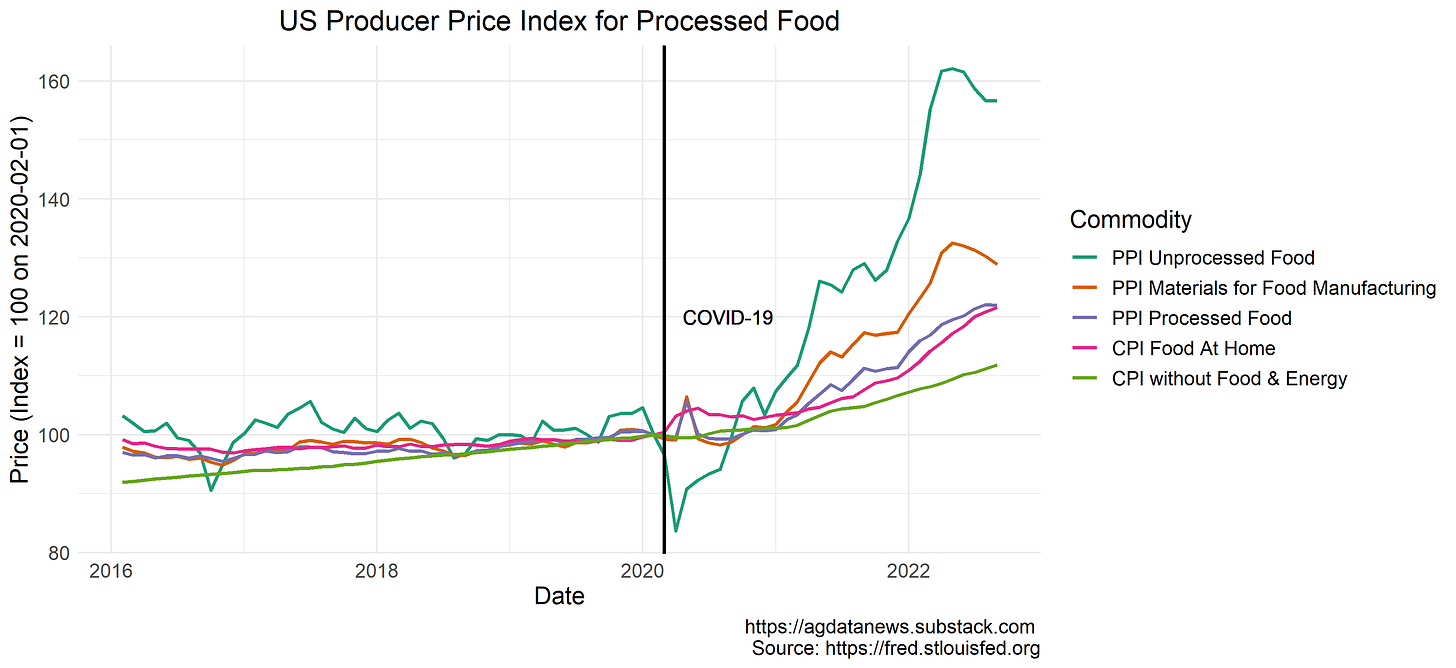

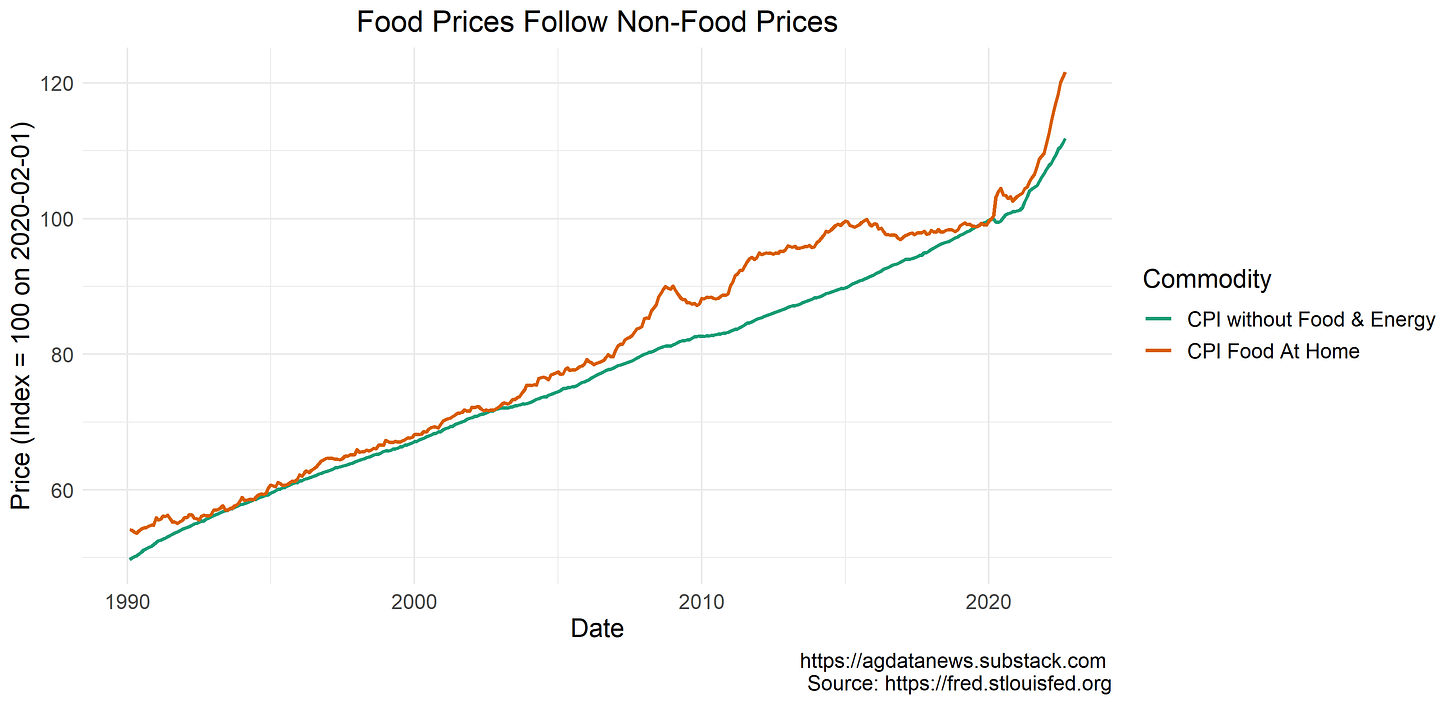

To understand the present and potential future, I look at two indices. First, the consumer price index for things that aren't food or energy, also known as the core CPI. This index strips out the things that bounce around a lot, so it is better indicator of future inflation.

Second, I look at the producer price index to see how prices are changing at different points in the supply chain. The consumer price index only shows prices at the end of the supply chain. The further up the supply chain you go, the more volatile prices are and the less informative they are about current and future consumer prices.

Prices for unprocessed food, such as fresh fruit that will be canned or raw corn, are up 87% from their low point in April 2020. They are up 57% since January 2020, and have declined from their early-summer peak. Materials for food manufacturing, such as milk products, frozen fruits and vegetables, or processed sugars, are up 29% since January 2020. They have also declined from their early-summer peak.

The price of food in the store is up 22% over the same period, but it has not declined since early summer. In these past few months, its changes better match the core CPI.

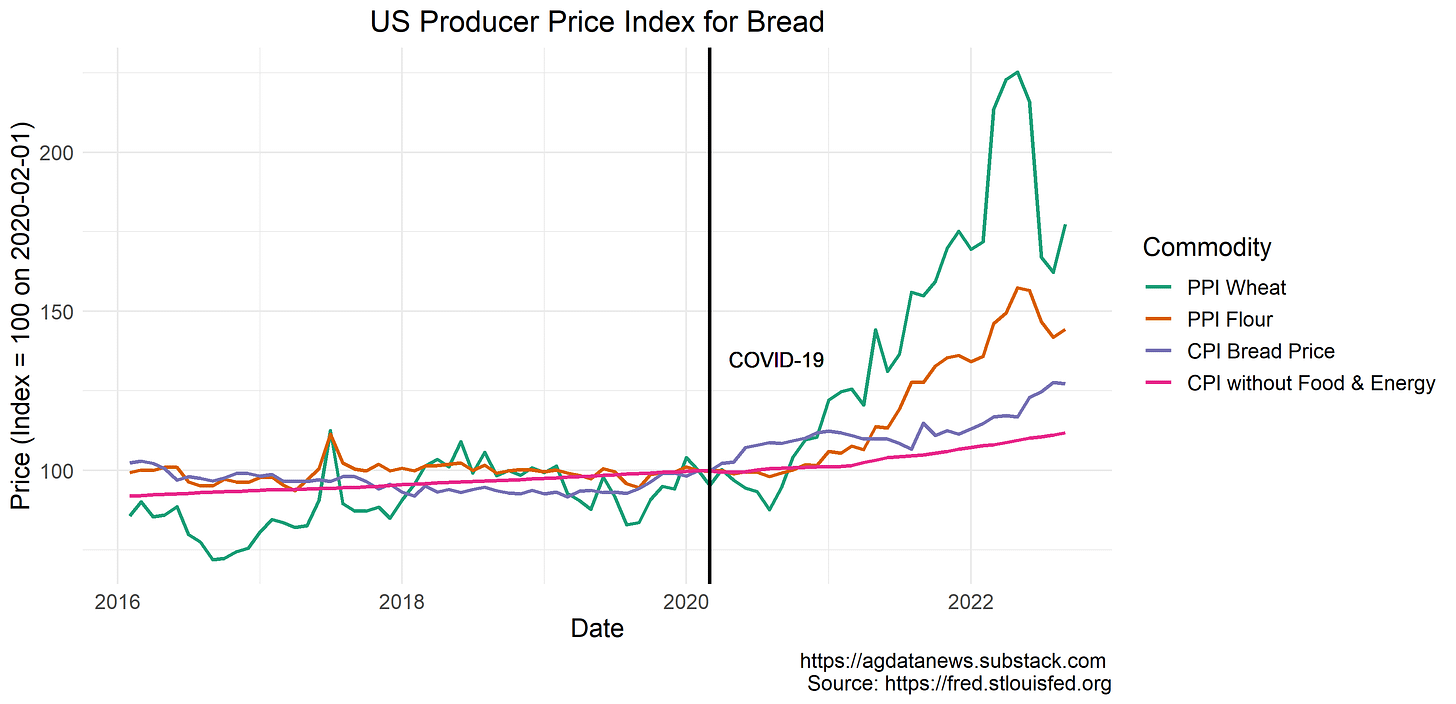

The same phenomenon is more apparent for individual products, such as bread. Wheat prices went up and down but remain high. Flour prices went up and down by less, but remain high. Bread price increases have been closer to the core CPI, although they are more volatile.

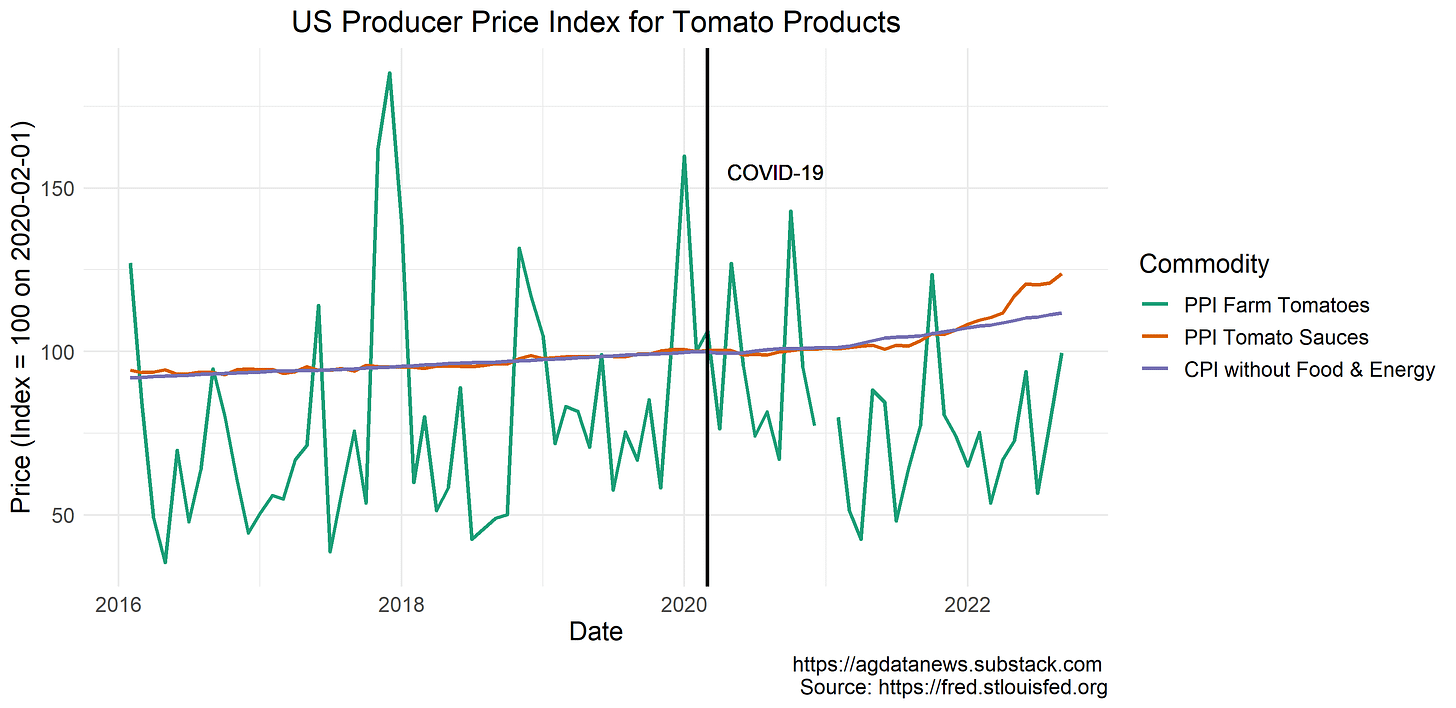

Here are tomatoes. The farm price is very volatile and the price of canned ketchup and other tomato sauces mostly follows core CPI (except for a curious bump up in April 2022).

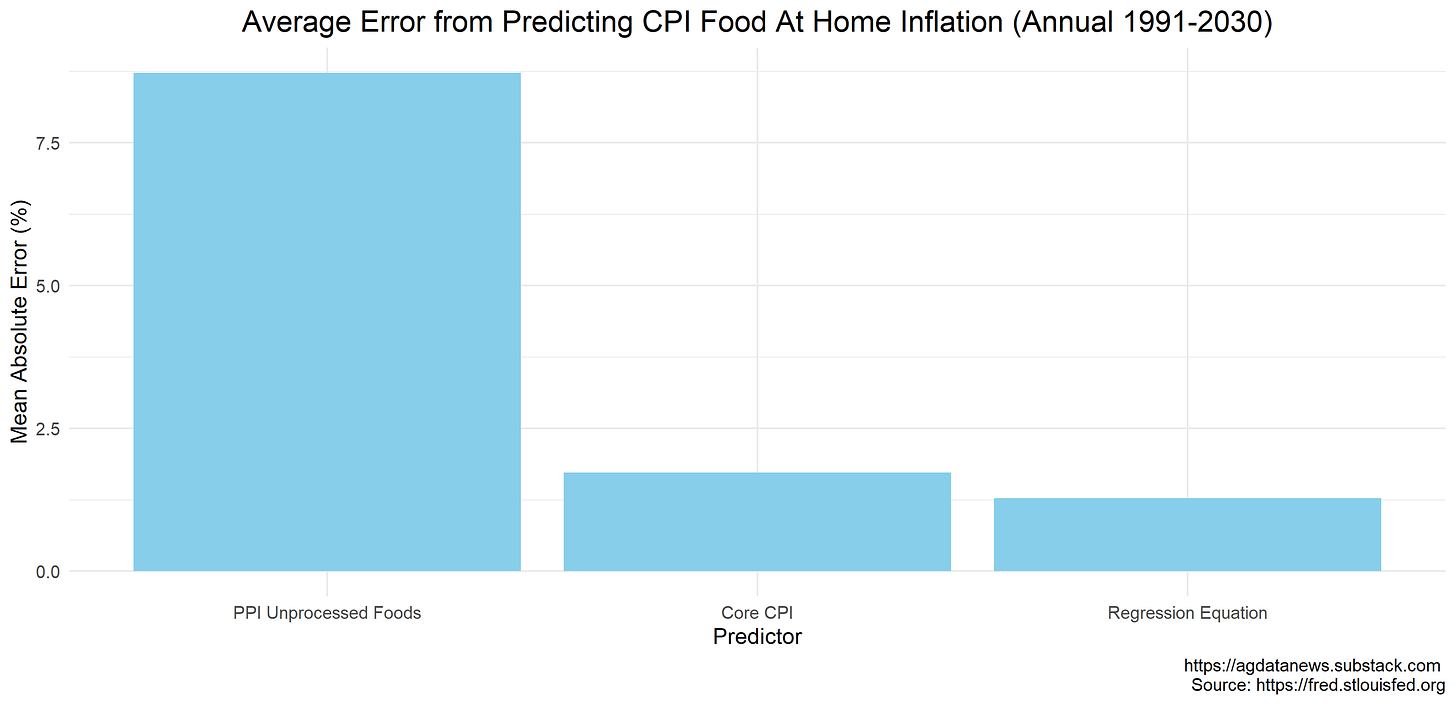

To put some numbers on this, imagine three models to predict inflation in grocery store prices.

% Change in CPI Food At Home = % Change in PPI Unprocessed Foods

% Change in CPI Food At Home = % Change in CPI without Food & Energy

% Change in CPI Food At Home = 0.10*(% Change in PPI Unprocessed Foods) + 1.18*(% Change in CPI without Food & Energy) + 0.05*(% Change in CPI Energy) - 0.85

The third prediction is from a linear regression model that predicts annual CPI food at home inflation using the three predictors. The model puts by far the most weight on the core CPI.

In the years from 1991-2022, predicting annual food inflation using the price of unprocessed foods yields an average error of 8.7%. The average error is 1.7% if we use the core CPI to predict and 1.3% if we use the regression model. For these calculations, I used annual September-to-September inflation since 1991 because September 2022 is the latest inflation data we have.

The USDA estimates that farm gate sales of food commodities made up 14% of the retail value of food in 2019. If farm prices were to double, we would expect food in the grocery store to increase by just 14%. Similarly, my regression model predicts that if farm prices were to double, then food in the grocery store would increase by 10%, all else equal.

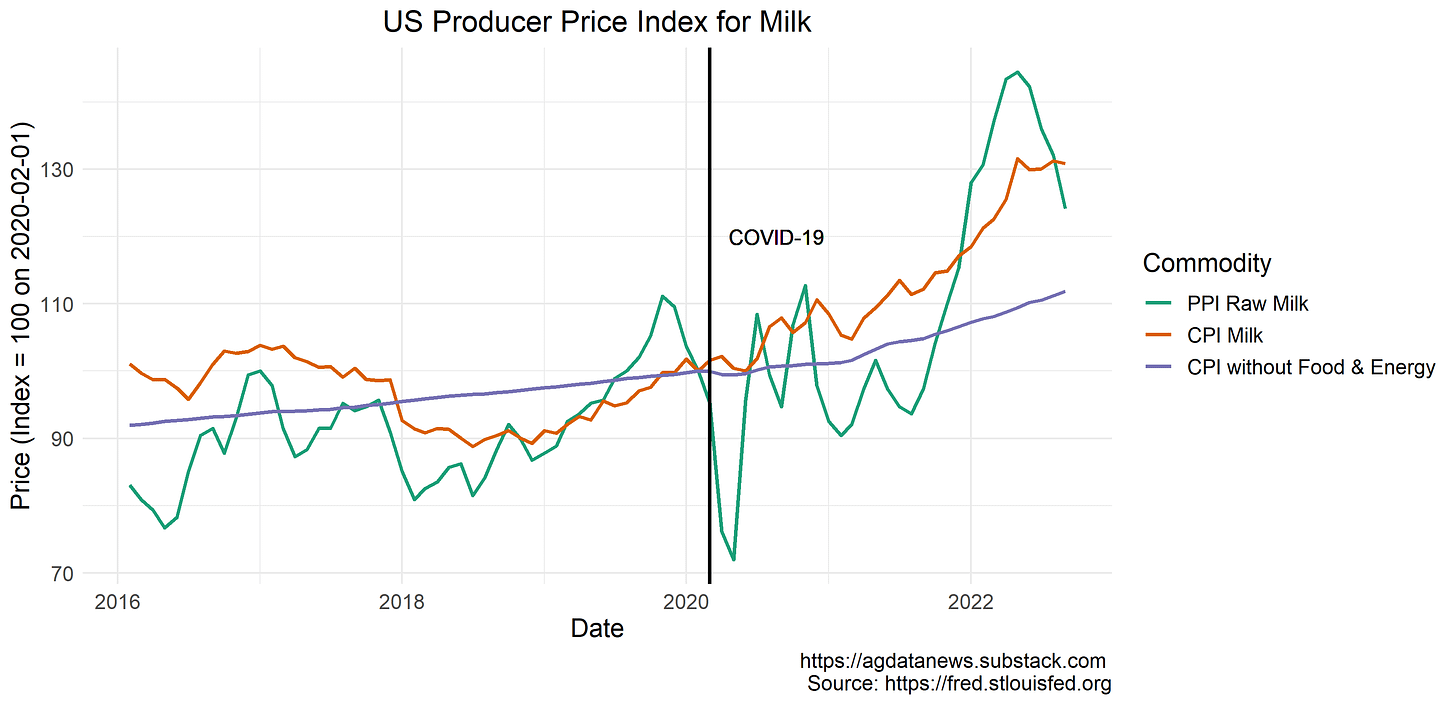

These numbers vary across commodities. If you are buying minimally processed food like milk, eggs, or fresh vegetables, then the prices in the store will be more closely tied to the farm price. But, on average across all the things we buy in the store, the core CPI is better indicator of what's happening and going to happen to prices.

Core CPI went up 0.6% last month, 3.4% in the past six months, and 6.7% in the past year. These numbers all point to annual inflation of 6-7% in the near future, until Federal Reserve interest rate increases begin to bite.

But there is good news. As prices for unprocessed food come down, which they will at some point, the gap between food prices and core CPI will close. This means food prices are likely to grow more slowly than prices in the rest of the economy in the next year or two.

I made the graphs and estimated the prediction model in this article using this R code.